Int. J. Dev. Biol. In Press

In Press

The Hydra FGF family – dispersed across the genome and expressed locally

Open Access | Original Article | Published: 23 December 2025

Abstract

Although the nonbilaterian Hydra has a simple body architecture, its signaling systems are as complex as those of Bilateria. We here add data to the fibroblast growth factor signaling system which has previously been identified in Hydra as essential for bud detachment. The localized expression patterns of its, now fifteen, FGFs indicate additional, yet unidentified, functions in sometimes very small subsets of cells at the body termini and/or during budding or in testes. Presence of a typical signal sequence (prediction >93%) in only 30% of the Hydra FGFs suggests mechanisms of action (and/or secretion) other than the canonical ones. A knockdown approach using siRNA revealed a potential role for Hv-FGF-c in tentacle morphogenesis. Our results document a high complexity of FGF signaling sites in Hydra and open the field for a detailed analysis of their functions.

Keywords

invertebrate, Cnidaria, FGF cluster, tentacle, signal peptide

Introduction

Fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) are essential players in cell migration, differentiation and proliferation across all tested animal phyla. Most FGFs are secreted and act as paracrine factors on cells carrying an appropriate FGF receptor tyrosine kinase (FGFR) which transduces the signal into the cell. FGFs either generate gradients attracting cells or cell collectives or they generate a microenvironment used e.g. in boundary formation or for the locally restricted differentiation of cell populations by generating microenvironments. Typical examples of FGF-dependent developmental functions include collective cell migration in vertebrate limb development (Ohuchi et al., 1997) or towards the Drosophila testes (Rothenbusch-Fender et al., 2017), the establishment of the modular lateral line organ in fish (Nechiporuk and Raible, 2008), boundary formation in the central nervous system of the flat worm and among vertebrate (Cebria et al., 2002; Gibbs et al., 2017) or the development of the fly heart or of branched organs as in the Drosophila tracheal system (Stathopoulos et al., 2004; Dossenbach et al., 2001) are well-known FGF functions.

FGF/Rs are eumetazoan-specific and they are even missing in the early-branched nonbilaterian phyla Placozoa, Porifera and Ctenophora (Bertrand et al., 2014). This essential signaling system has thus evolved in the last common ancestor of Bilateria and their sister group, the prebilaterian Cnidaria, where it exists in considerable complexity already (Rebscher et al., 2009; Bertrand et al., 2014). One pair of FGFs and FGFRs acts in axis formation and in apical cell differentiation in the sea anemone Nematostella (Anthozoa) (Matus et al., 2007; Rentzsch et al., 2008; Technau 2020). FGFR signaling using FGFs is essential for the differentiation of sensory and support cells in the apical organ of this anthozoan (Sabin et al., 2024). In the solitary fresh water polyp Hydra (Hydrozoa) two FGFRs (Sudhop et al., 2004; Rudolf et al., 2013; Suryawanshi et al., 2020) and five FGFs have been identified (Krishnapati et al., 2013; Lange et al., 2014; Siebert et al., 2019). Functional assays identified FGFR signaling as essential for bud detachment by establishing, in a Notch-dependent fashion, the boundary between bud and parent and controlling the timing of detachment (Sudhop et al., 2004; Münder et al., 2010; Hasse et al., 2014; Holz et al., 2017). The dynamic transcriptional upregulation of Hv-FGFRa/kringelchen (the gene for FGFRa) and Hv-FGFR-b in vegetative buds and in tentacle buds as well as its weak constitutive transcription along the whole body indicated additional functions (Sudhop et al., 2004; Suryawanshi et al., 2020). This hypothesis was supported by the localized upregulation of a putative FGF8 homologue, Hv-fgf-f (Lange et al., 2014). Transcription of this FGF is dynamically upregulated at all termini and in almost all transition and boundary zones that are crossed actively by migrating cells or passively by tissue exported into buds or tentacles - or towards the termini. Since three of the five Hydra FGFs known in 2014 appeared to be ubiquitously expressed, the question arose what might be their functions.

Compared to Bilateria, the Hydra body is simple and cell proliferation, differentiation and migration are permanently active in these potentially immortal polyps. The tube-like polyps carry, in their apical part, a mouth and terminally differentiated tentacles equipped with stinging cells (nematocytes) which are continuously replaced by nematoblasts immigrating from the body column. The gastric region serves digestion as well as vegetative propagation (budding) by export of tissue into laterally sprouting young polyps. A terminally differentiated basal disk attaches Hydra to the substrate using a soluble chitin gel (Seabra et al., 2022). The body wall is formed by monolayered ecto- and endodermal epithelia consisting of multifunctional epitheliomuscle cells which are anchored in and contact each other through a thin, intermitting extracellular matrix, the mesoglea (Shimizu et al., 2008; Aufschnaiter et al., 2011). These epitheliomuscle cells are essential for morphogenesis. During vegetative budding FGFR signaling in their apico-lateral cellular compartment is the critical signaling system for cell shape changes allowing detachment from the parent (Holz et al., 2020).

Potential immortality is given to Hydra vulgaris by four stem cell lines (Holstein, 2023). Proliferation of the two ecto- and endodermal stem cell lines in the mid-body generates a flow of epithelial tissue towards the terminally differentiated basal disc and head region and into the buds. The third and fourth, both interstitial, stem cell lines (I-cells) provide precursors (the so-called small i-cells) for neurons, stinging cells, certain gland cells and from a different subset also for the germ cells, eggs and sperm. These precursors migrate actively towards their final destinations and the cell clusters are well recognizable in single cell transcriptomes (Siebert et al., 2019). Precursors of the stinging cells, the nematoblasts, migrate mainly towards the tentacles and integrate as terminally differentiated nematocytes into so-called battery cells. Battery cells are epitheliomuscle cells which reach the tentacle base through the continuous tissue shift, and arrange along the tentacles at regular distances. The immigrating stinging cells mount in individual apical “pouches” formed by the battery cells and anchor basally in the mesoglea by an adhesion complex reaching through the battery cell cytoplasm and their cell membrane (Novak and Wood, 1983). A regular pattern of nematocyte subtypes is always established within the battery cells: one or two large stenoteles in the center are surrounded by small desmonemes and slim isorhiza. This arrangement generates a pattern of the fully equipped battery cells resembling beads on a string along the tentacle. Obviously, signals for homing and arrangement must exist and be received by the cells crossing the body-tentacle boundary to yield this regular arrangement. However, the nature of these signals is unknown.

Since FGFs are attractive candidates for tasks like cell guidance and differentiation, we reinvestigated the expression characteristics of the previously identified Hydra FGFs Hv-fgf-a, Hv-fgf-b, Hv-fgf-c, Hv- fgf-e and Hv-fgf-f (Lange et al., 2014). An additional re-evaluation of the available Hydra EST databases, furthermore, revealed ten more peptides with the typical FGF core. For all of them the typical FGF protein structure is predicted and all of them are transcribed in restricted domains. Focusing on Hv-fgf-b and Hv-fgf-c, which are expressed in tentacles or at their base, a knockdown by siRNA revealed a striking role of Hv-FGF-c for proper tentacle morphogenesis in the transgenic Hydra vulgaris Traffic Light line.

Results

Database search and bioinformatic analysis identifies 15 Hydra FGFs

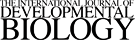

The core domains of five previously identified Hydra vulgaris AEP FGFs (Hv-FGF-a, Hv- FGF-b, Hv-FGF-c, Hv-FGF-e, and Hv-FGF-f) (Lange et al., 2014) were used for protein BLAST and identified ten additional potential Hydra FGFs in the EST databases. Their sequence IDs (NCBI and Hydra AEP Genome Project Portal sequence) are listed in (supplemental Table S1A). Analysis of the Hydra FGFs properties using Expasy ProtParam (https://web.expasy.org/protparam) characterized all of them as small hydrophilic and highly basic proteins with molecular weights between 18,6 and 32,7 kDa and an estimated isoelectric point (pI) between 8.1 and 10.0 (supplemental Table S1B). Presence of the characteristic FGF core domain (Mohammadi et al., 2005) was verified for each of the predicted FGF candidate proteins in comparison to vertebrate FGF1, FGF2 and FGF8 (Supplement Fig. S2_1) using SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de) and InterPro (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro). Structure prediction by modelling with the Expasy Swiss Model server (https://swissmodel.expasy.org) yielded the typical FGF beta-trefoil / donut-like structures for all Hydra FGFs similar to the vertebrate FGFs (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Predicted protein structure of the fifteen Hydra fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) and genomic arrangement of the ten FGFs located on chromosome 03.

(A) The predicted Hydra FGF protein structures (https://swissmodel.expasy.org) show a beta trefoil structure like Homo sapiens (H.s.) FGF1, FGF2 and FGF8. (B) Distribution of the Hydra FGF genes on chromosome 03 is indicated by using the 5’ end position of the respective gene (BLAST analysis of the cDNAs in the two genomic libraries, Hydra T2T_AEP (NCBI RefSeq assembly GCF_038396675.1) and Hydra T2T_105 (GCF_037890685.1-RS_2024_06) representing the respective haplotype. Neighboring genes in green (FGFR and FGFR-like in both genomes; FGF-j and FGF-i in the Hydra T2T_105 genome, only). Features and ranges including the remaining five Hydra FGFs on chromosomes 09, 12 and 13 are given in Supplement Fig. S3_1 and Supplement Fig. S3_2).

Chromosomal distribution of Hydra FGF genes

Since some of the 22 vertebrate FGFs are clustered in the genome (reviewed in Itoh and Ornitz, 2004), we analysed the distribution of the 15 Hydra FGFs in the genomic libraries of two Hydra strains, Hydra T2T_105 versus Hydra T2T_AEP. BLAST search revealed a dispersed localization on four chromosomes. In both genomes, ten FGF genes are localized on chromosome 3, one each on chromosome 09 (Hv-fgf-n) and chromosome 13 (Hv-fgf-a), respectively, and three FGF genes (Hv-fgf-g, -o and -k) on chromosome 12 (Fig. 1B and Supplement S3). Moreover, a fragment of 409 nucleotides (nt) with 91% identity to Hv-fgf-c, spanning the 3’ coding and 3’ untranslated region, was revealed on chromosome 08 in the HydraT2T_AEP library (loc136084282 isoform x2 and loc124817691 isoform x2, see Supplement S3_1). This fragment is not annotated as a gene.

In the Hydra AEP genome, all 15 FGF genes are separated from each other by several other genes. In contrast, in the Hydra magnipapillata wt105 genome Hv-fgf-j and Hv-fgf-i, are placed as neighbors at a distance of 22.388 nt with no other genes identified in between. Interestingly, the gene for FGFRa, Kringelchen, (Sudhop et al., 2004) and a gene sequence encoding several alternative frames for smaller FGFR-like proteins are placed between the Hv-fgf-m and Hv-fgf-h genes. While the FGFR and FGFR-like sequences are direct neighbors, they are separated from the two FGFs by other genes (Fig. 1B).

Several Hydra FGFs have been annotated with identical/redundant names in the genomic libraries e.g. FGF1 is given three times in the Hydra T2T_AEP and 4 times in the Hydra 2T2_105 libraries to different genes (Supplement S3_1 and Supplement S3_2). We therefore propose to rename (annotate) the FGFs according to the letter code we had started to use for the first 5 FGFs in 2014 (Lange et al., 2014). This should help to unequivocally assign the expression pattern and functions of each Hydra FGF and to avoid the direct reference to the 22 FGFs numbered in vertebrates

Five Hydra FGFs contain a well-recognizable N-terminal signal sequence

Since most bilaterian FGFs act in a paracrine, extracellular way (reviewed in Ornitz and Itoh, 2022) and use an N-terminal signal sequence for secretion, we searched for signal sequences in the Hydra FGFs. SignalP 6.0 (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/SignalP-6.0) predicted with 93 - 99.9 % probability a signal peptide for five Hydra FGFs (see supplemental Table S1B and Supplement Fig. S2_1) (Hv-FGF-e, Hv-FGF-f, Hv-FGF-h, Hv-FGF-l, and Hv-FGF-m). Another four FGFs (Hv-FGF-c, Hv-FGF-g, Hv-FGF-i, and Hv-FGF-p) were assigned a medium to low probability for a signal sequence (54 % - 69 %) and in the remaining six Hydra FGFs presence of a signal sequence is questionable (Hv-FGF-j and Hv-FGF-n) or denied (Hv-FGF-a, Hv-FGF-b, Hv-FGF-k, and Hv-FGF-o).

It would be highly desirable to use purified Hydra FGFs for bioassays. To obtain a first clue whether the Hydra FGFs are expressed and secreted in a heterologous system, we used the eukaryotic HEK293T expression system. The coding region of two Hydra FGFs with high probability for a signal sequence (Hv-FGFe und Hv-FGFf), of one with a medium probability (Hv-FGFc) and one with no identifiable signal peptide (Hv-FGFb) were cloned in the pcDNA 3.1-myc-His A expression vector and transfected in HEK293T cells. The vertebrate cells expressed the tagged Hydra FGFs at high levels despite their alkaline pI. All four FGFs were detected within the cells by an anti-myc antibody in the cytoplasm, either dispersed within the whole cell or in granulae below the cell membrane and/or in filopodia and varicosity-like thickenings of filopodia (Supplement Fig. S2_2). Hv-FGF-e and Hv-FGF-f were isolated from cell extracts by affinity purification via the His-tag, but none of the Hydra FGF proteins was detected in the cell culture medium (Supplement Fig. S2_3). On a Western Blot, however, multiple bands were detected (not shown). Taken together, HEK293T is a promising system to express Hydra FGFs for future bioassays, but their secretability has to be investigated and purification steps optimized.

All Hydra FGFs are transcribed locally restricted

In contrast to the previously reported almost ubiquitous expression of the Hydra FGFs Hv-FGFa, Hv-FGFc and Hv-FGFe (Lange et al., 2014), a reduced antisense RNA probe concentration as well as additional destaining steps revealed localized expression domains in Hydra tissue (Fig. 2 for Hv-fgf-b and Hv-fgf-c; Supplement Fig. S4, plate I for Hv-fgf-a and Hv-fgf-e and plate II for Hv-fgf-f). All of the newly identified FGFs are as well expressed in restricted expression domains. Supplement Fig. S4, plates III and IV provide a first overview. Their expression pattern as well as that of Hv-fgf-a and Hv-fgf-e will be summarized here only shortly since our further focus was on Hydra FGF-b and FGF-c. As documented in Supplement Fig. S4 several of the new Hydra FGFs are upregulated in terminal structures (Supplement Fig. S4, Plate III – IV), particularly in the basal disc or in tentacles (Hv-fgf-b, Hv-fgf-f, Hv-fgf-I, Hv-fgf-j, Hv-fgf-p). Some are expressed complementary to others as are the ectodermal Hv-fgf-i and the endodermal Hv-fgf-j or Hv-fgf-p in tentacle tips. Some are strongly upregulated in testes like Hv-fgf-h (early testis) and Hv-fgf-k (maturing testis) or weakly like Hv-fgf-f at the testis base. Dynamic changes with switches between ecto and endodermal patterns are obvious like, for example, in the Hv-fgf-l transcription in the early bud field and developing young polyp. The Hv-fgf-l expression domain partially overlaps and resembles Hv-fgf-f, an FGF which is transcribed in cells adjacent to both Hydra FGFRs at the bud base (Supplement Fig. S4, plate II; (Lange et al., 2014)). For Hv-FGF-n only a sense signal (speckled upper body column), but no antisense signal was detected (not shown).

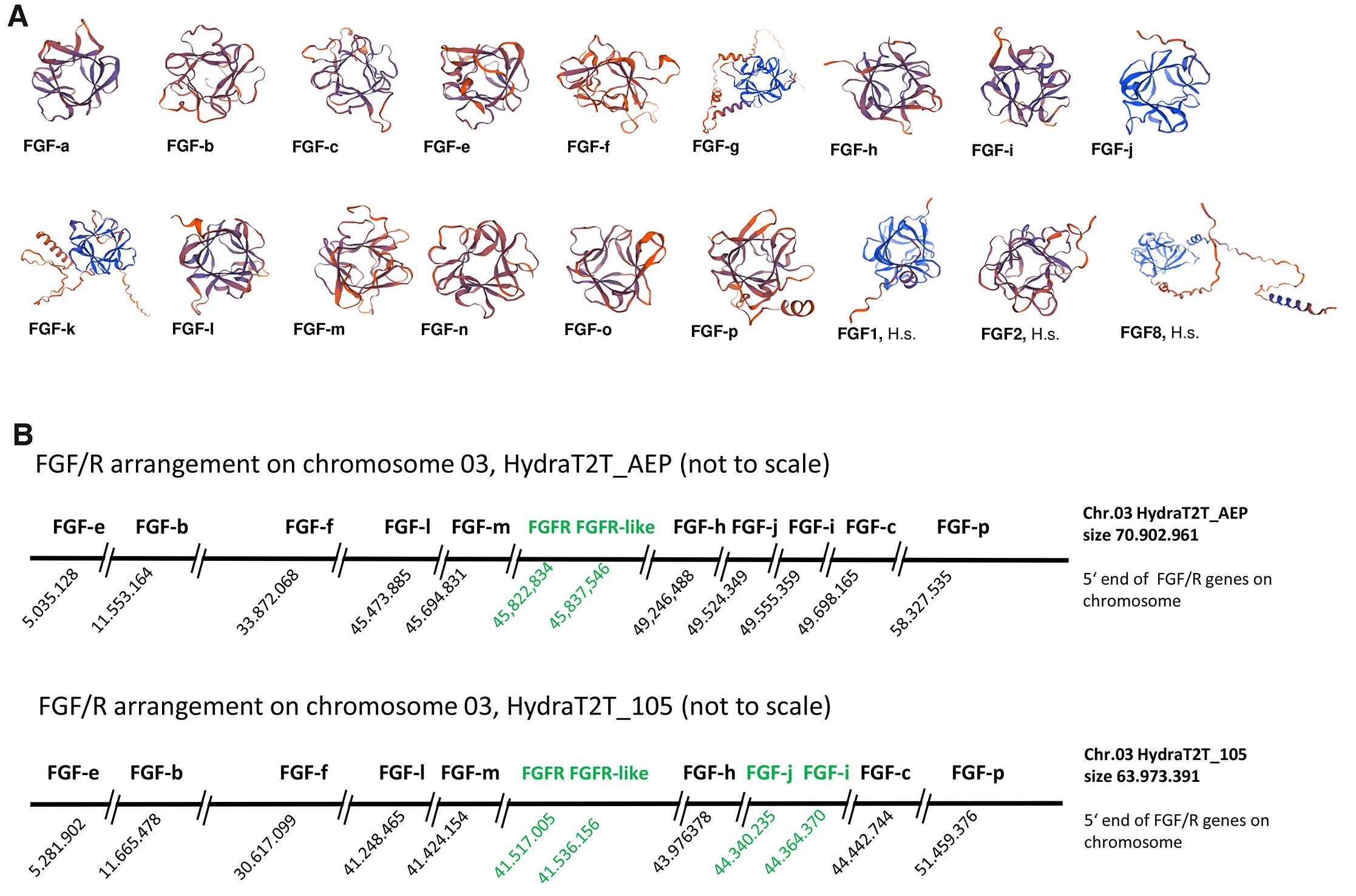

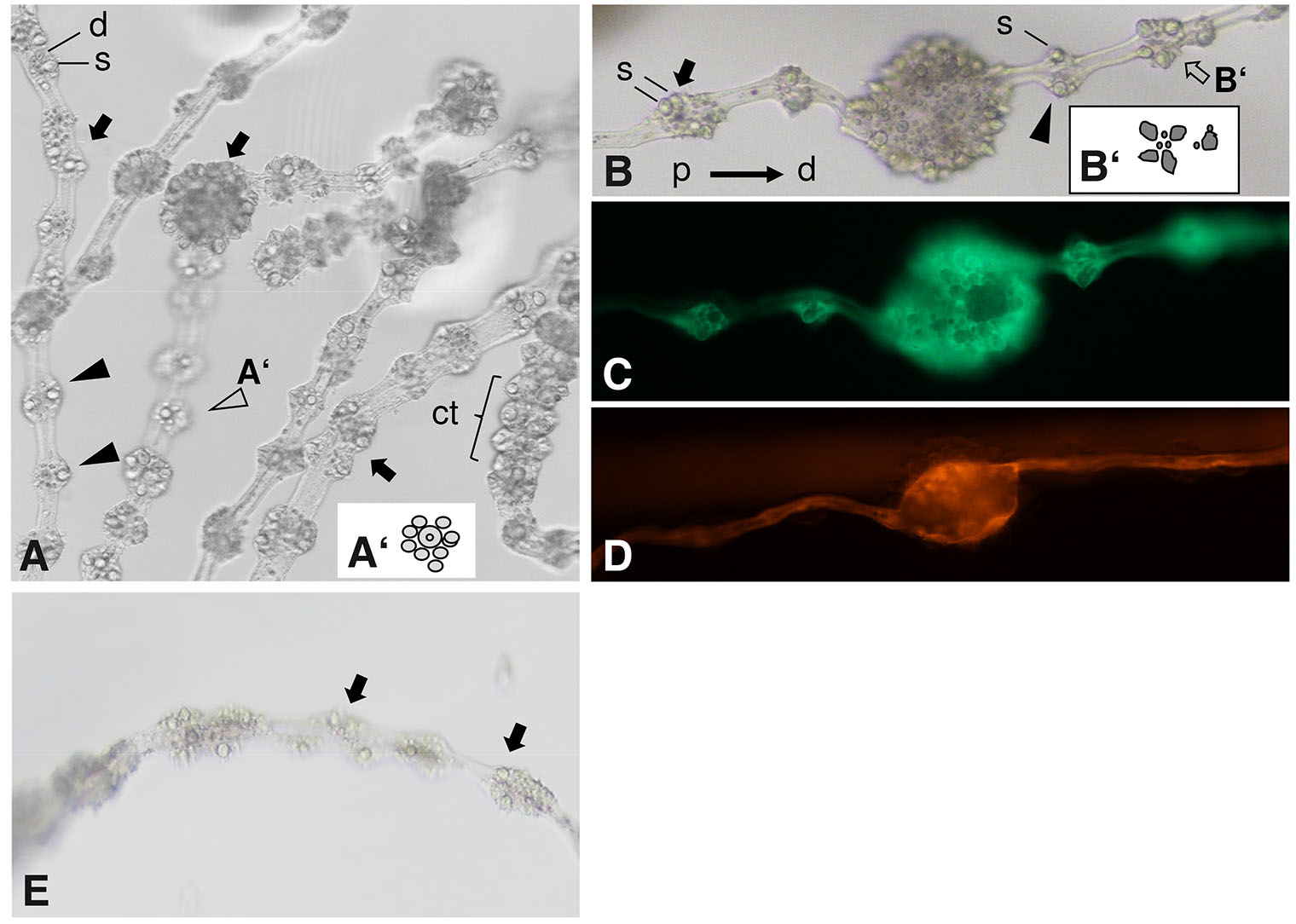

Fig. 2. RNA transcription patterns of Hv-fgf-b and Hv-fgf-c.

In situ hybridization of antisense RNA probes for Hv-fgf-b (A - I’’) and Hv-fgf-c (J – J3’). Budding stages are given for Hv-fgf-b according to Otto and Campbell (1977). Abbreviations: bb bud base, ec ectoderm, en endoderm, fp foot pore, m mesoglea, st stalk region between basal disk and budding zone, tb tentacle bud, tez prospective tentacle zone. (J1’ – J2’) Hv-fgf-c positive tentacle base cells (arrows) are numbered to highlight their chain-like arrangement. (J3, J3’) Optical focus on the strongest staining cell with cytoplasmic extensions and an unstained central part (arrow). Scale bars, 100 µm unless indicated otherwise.

This first overview documents clear patterns which suggest locally restricted functions in specialized, terminally differentiated or differentiating cells (tentacle tip, foot pore, testis) or in cells changing their shape like at the tentacle base, in the evaginating bud or later at its base.

Transcription patterns of Hv-fgf-b and Hv-fgf-c

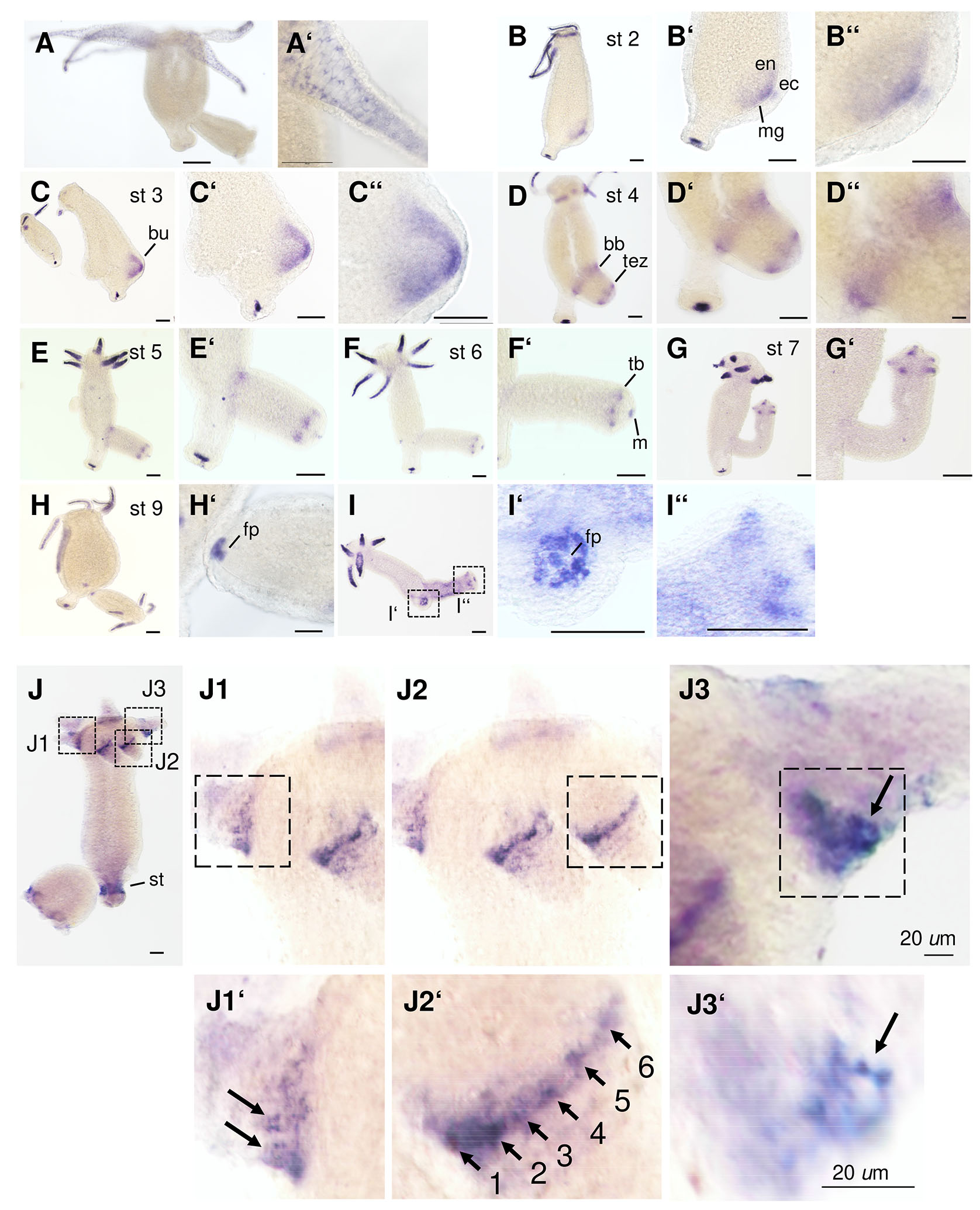

In the following we focus on Hv-FGF-b and Hv-FGF-c (Fig. 2), their mRNA expression patterns and a first functional analysis using siRNA. Hv-fgf-b mRNA is localized endodermal with the exception of a transient weak ectodermal domain at the tip of the early bud, stage 1-2 (Fig. 2 B-B’’). The gene is transcribed strongly in the tentacle endoderm and detected at a prolonged incubation time in a few cells of the basal disc endoderm (Fig. 2 A–I’’). A staining protocol with a highly diluted probe and short exposure times revealed small endodermal tentacle cells resembling round nematocytes (stenoteles) and few nests of small cells plus a triangular signal right between the huge epithelial cells which resembles neurons (Fig. 2A’ and Fig. 3 A,B). Recently published data reported the lack of neurons in tentacle endoderm (Keramidioti et al., 2024). We therefore carried out a single cell analysis of the upper body region. A few stained stenoteles and smaller cells, resembling desmonemes (Fig. 3 C,C’) were detected, but no neurons. As alternative explanation we take into consideration a triangular signal resulting from the cytoplasm of the highly vacuolized endodermal epithelial cells which is compressed into one corner.

Fig. 3. In situ hybridization signals of Hv-fgf-b in the tentacle endoderm.

(A,B) Tentacles digitally enlarged from Fig. 2A; endodermal signals resembling neurons (open arrows) and nematocytes (closed arrows) below the mesogloea (mg). (C,C‘) Single cell preparation of a Hydra head, cut close to the tentacles. st stenotele, de desmonemes.

Prolongation of the staining time blurred the above-described pattern and resulted in a dark blue tentacle endoderm (mainly by staining endodermal epithelial cells). Additional Hv-fgf-b positive basal disk cells were now disclosed around the foot pore (Fig. 2 B-I,I’). Moreover, transcription was found upregulated throughout bud evagination: from bud stages 1-3 (evagination phase) in the whole bud endoderm with a maximum in the bud tip endo- and ectoderm (Fig. 2 B-C’’), in bud stages 4 and 5 (elongation phase), in a transient broad endodermal ring of cells at the bud base and in the prospective tentacle zone (Fig. 2 D-E,E’) was established. Thereafter endodermal cells in tentacle buds and transiently surrounding the mouth (Fig. 2 F-G’,I’’) as well as at the foot pore (Fig. 2 H–I’,I’’) became positive and the adult pattern was attained shortly before detachment from the parent (Fig. 2H).

Hv-fgf-c, in contrast, was transcribed ectodermal at the tentacle bases and in a broad belt surrounding the stalk, distant to the basal disc (Fig. 2J). This mature pattern was attained in growing buds from bud stage 7 onwards in tentacles and from stage 8 onwards in the stalk (not shown). In contrast, to Hv-fgf-b, the gene is not transcribed in additional regions. Interesting is the chain-like arrangement of Hv-fgf-c positive cells around the tentacle base (Fig. 2 J1-J2’) with a stronger signal in cells at the aboral tentacle base close to the body column (Fig. 2 J1-J3). Here, single cells were distinguishable which seemed to either form strongly staining cytoplasmic protrusions connecting to other cells (Fig. 2 J2’ between cells 4-5) or proximal placed, huge cells with short protrusions (Fig. 2 J1’,J3’). By analyzing single cell preparations with in situ hybridization, these cells could, unfortunately, not be further characterized (data not shown). In summary, both Hv-fgf-b and Hv-fgf-c are interesting markers for tentacle-specific endo- and ectodermal cell types.

RNA interference for Hv-fgf-b and Hv-fgf-c

Since Hv-fgf-b and Hv-fgf-c are expressed in the tentacle endoderm and in specific ectodermal cells at the tentacle base, respectively, we asked whether a knockdown using siRNA electroporation affects tentacle morphology. Using the Hydra vulgaris strain AEP which is used widely as the strain to generate transgenic polyps, no morphological changes were observed. To better visualize ecto- and endoderm, we used the Traffic Light Hydra line which is a chimaera between the Hydra vulgaris AEP watermelon strain and Hydra vulgaris AEP ss1 YPet (Wang et al., 2022).

In four independent experiments we electroporated siRNAs once in early budding (for Hv-fgfr-a) or nonbudding animals (Hv-fgf-b and -c; negative control). Using a well-established protocol (Lommel et al., 2017), Hv-fgfr-a siRNA as a positive control was electroporated in polyps bearing stage 1-3 buds (Supplement Fig. S5). Scrambled GFP siRNA (scrGFP) or siRNA pGL2 served as negative controls (see Supplement Fig. S6 for evaluation of siRNA effects). Hv-fgf-c downregulation was clearly visible (S6, A-C’). All polyps lost their tentacles within a couple of hours after electroporation but recovered within two days post electroporation (dpe) and were able to feed again on day 2 dpe. Morphology was analyzed in detail from day 5 or 6 after electroporation onwards. Neither the scrGFP nor the pGL2 nor the Hv-fgf-b siRNAs had visible effects on bud or parent morphology - except split tentacles occurring in almost all the electroporation experiments at low incidence of 1-2 animals per 30 (not shown). Between 50 - 60% of the positive control, Hv-fgfr-a siRNA treated polyps carrying stage 1-3 buds, developed the known branching phenotype (Sudhop et al., 2004; Hasse et al., 2014) as shown in Supplement Fig. S5.

A striking phenotype occurred in 40 - 70% of the Hv-fgf-c siRNA-treated animals which was not seen with any of the other siRNAs (Fig. 4; raw data in Supplement S5_2). The siHv-fgf-c – treated polyps developed tentacles with (multiple) irregular shaped battery cell arrangements and even packed battery cell zones resembling in their most expressed form nodules bulging from the tentacles without a distinguishable separation of the battery cells (Fig. 4 A-G, Fig. 5 A,B). The nodule shape was fixed and they neither contracted nor elongated. All other tested siRNAs resulted in normal tentacles (Fig. 4 H-M for scrGFP and Fig. 4 N–S for Hv-fgf-b; Supplement S5 A,B for Hv-fgfr-a).

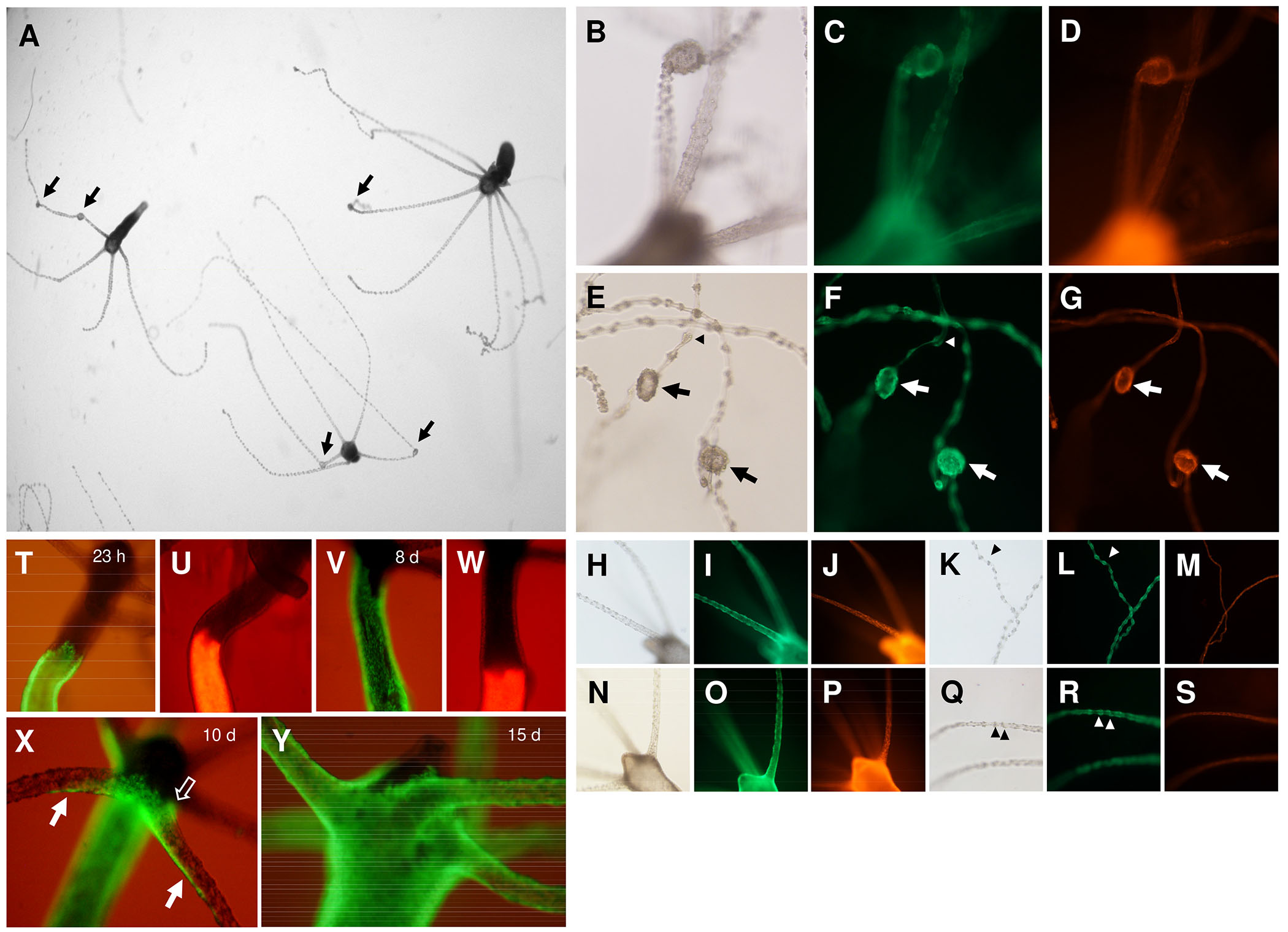

Fig. 4. Knockdown of Hv-fgf-c by siRNA and ectodermal tissue dynamics in the Hydra head.

(A–S) Budless transgenic polyps were subject to siRNA electroporation and their morphology evaluated on day 12 (A–G) Hv-fgf-c, (H-M) scrGFP and (N–S) Hv-fgf-b. (A) Picture taken by a dissection microscope, Hydra anesthetized in 1 mM linalool (Goel et al., 2019). (A-G) Tentacle nodules (arrows) formed by a bloated endoderm with tightly clustered ectodermal battery cells; apparently normal battery cells (arrow heads) arranged like beads on a string distant from adjacent battery cells. Green fluorescence is ectodermal, red fluorescence is endodermal. (T-Y) Tissue dynamics of ecto- and endoderm towards the head analysed in transplants of normal upper body half and transgenic lower body, 15 days post transplantation (dpt). (T,U) 23 h post transplantation; (V,W) 8 dpt: the ectoderm has moved quickly towards the head, the endoderm is stalled; (X) 10 dpt: ectodermal cells cross the body-tentacle boundary at the lower tentacle base and quickly spread along the lower side of the tentacle (arrow) or have already enclosed the complete tentacle base circumference (open arrow); (Y) 15 dpt: tentacles are completely covered by transgenic ectodermal cells.

Fig. 5. Morphology of Hv-fgf-c by siRNA treated tentacles.

(A-D) Hydra AEP traffic light. (A) Overview of several elongated tentacles with aberrant battery cell arrangements or nodules formed by bloated endoderm and tightly packed battery cell clusters (arrows) besides normal-appearing battery cells (arrow heads); stenoteles (s) and desmonemes (d) are labelled. (A’) scheme of a normal battery cell (open arrowhead); a contracted (ct) normal tentacle is visible on the right. (B) Tentacle with a central nodule and flanking aberrant battery cells (arrows) as well as with an almost normal battery cell (arrowhead). (s) stenotele (the biggest, toxin-filled nematocyte). (B’) Scheme of one of the aberrant elongated battery cells (open arrow). Hydra anesthetized in 1 mM linalool for max. 10 min. (A,B) 40 x magnification, DIC optics; (C,D) fluorescence detected (C) ectodermally using a GFP/FITC or (D) endodermally by a Rhodamine/TRITC fluorescence filter set. (E) Wild type Hydra AEP, 6 dpe. One tentacle with minor irregularities in battery cells (arrows). Left: missing nematocytes, right: three stenoteles in one position.

Within the nodules evoked by siHv-fgf-c, the endoderm was bloated and covered with multiple ectodermal battery cells. The pattern of nematocytes in the nodules was irregular with an extreme amount of stenoteles packed within each nodule (Fig. 5 A,B) instead of the regular pattern consisting of one or two central stenoteles per battery cell surrounded by multiple, smaller isorhizas and desmonemes (compare to Fig. 5 A’,B’). Feeding the animals evoked normal reactions with multiple stenoteles ejected from the nodules (not shown). The tentacle endoderm in the unchanged tentacle regions appeared smooth and without any signs of endodermal bloating (Fig. 4 G,M,S and Fig. 5D). First aberrant tentacles were observed on day 5 dpe and persisted until at least day 21. Re-evaluation of the Hydra AEP siHv-fgf-c experiments yielded a single case of tentacles with irregular shaped / equipped battery cells (1/30) and none in the positive and negative controls (Fig. 5E). The phenotype of tentacle nodules thus occurred in the Hydra AEP Traffic Light strain while the wild type Hydra AEP showed only minor disturbances of the battery cell pattern if any.

Since battery cells enter the tentacles from the body column and not from the hypostomal side (Hobmayer et al., 2012), we monitored the dynamics of tissue movement towards the head and into the tentacles of transplants from transgenic and nontransgenic Hydra polyps. To this end polyps were bisected at 50% body length and a lower transgenic half transplanted to an upper nontransgenic one. Transplants joined and healed completely within 2 hours. Monitoring tissue movement after 1, 8, 10 and 15 days revealed a quick movement of ectodermal tissue and a very slow one of endodermal tissue (Fig. 4 V,W) as described by others (Campbell 1967). The ectodermal epithelial cells entered the tentacles from the lower side no matter whether control polyps or Hv-fgf-c-siRNA polyps (6 dpe) were used. They moved quickly towards the tentacle tip forming a transient green stripe on its lower side (Fig. 4X) for 2-3 hours. About 4 hours later epithelial cells had reached the upper part of the tentacle base and closed in forming a complete ring. On day 15, the tentacles were completely covered by ectodermal transgenic cells (Fig. 4Y). Interesting is the dynamics of this tissue movement – a very fast entrance into the lower side of the tentacles, a trailing movement on the upper side of the tentacle and a slow movement of tissue between the tentacles and into the hypostome. This kinetics was similar in control and siHv-fgf-c animals.

Taken together, the knockdown of Hv-fgf-c induces tentacle nodules and irregular shaped battery cell arrangements in Hydra AEP Traffic light. Their occurrence on day five correlates with the kinetics of epithelial cells (= battery cells) covering a tentacle completely.

Discussion

In this study, we analysed fifteen Hydra FGF-encoding genes identified in the databases, describe predicted properties of these peptides, document their highly localized expression patterns in the polyps and used siRNA knockdown to shed light on potential functions of Hv-FGFb and Hv-FGFc in tentacles. As a proof of concept, heterologous expression of four FGFs in HEK293T cells was successful. We will in the following discuss shortly the properties and expression patterns of Hydra FGFs and, in more detail, the implications of the siRNA knockdown of Hv-fgf-b and Hv-fgf-c.

The properties of Hydra FGFs resemble bilaterian FGFs, but are they secreted?

All fifteen Hydra FGFs show typical characteristics of vertebrate FGFs (for recent review see Ornitz and Itoh, 2022) including the beta-trefoil structure, a well-identifiable core domain, an alkaline pI and a molecular weight between 20 and 37 kDa. Differing from vertebrates is that only five of the fifteen Hydra FGFs, within them Hv-FGFe and Hv-FGFf, carry an N-terminal signal peptide predicted with high probability. A signal peptide is usually a good indicator for a secreted protein and most bilaterian FGFs act as paracrine or autocrine growth factors either using a signal sequence or, rarely, a noncanonical secretion mechanism like FGF1 and FGF2 (Ornitz and Itoh, 2022). In pilot experiments to obtain FGF proteins for bioassays, we expressed four FGFs in HEK293T cells. These have been used successfully to express Hydra proteins including secreted Wnt proteins (Vogg et al., 2019; Lengfeld et al., 2009). Hydra FGF localization in the cytoplasm and in filopodia of HEK293T cells was as expected, but most of the proteins located to submembrane granulae. Furthermore, despite affinity-purification, Hv-FGFe and Hv-FGFf were detectable within cell extracts, exclusively, and not in the cell culture medium. Whether the granular accumulation is due to secretion problems as known for vertebrate FGFs when flanking or internal sequences affect secretion (Miyakawa and Imamura, 2003) remains to be shown.

Given the lack of well-supported signal peptides in ten of the fifteen FGFs and considering the close spatial expression of Hydra FGFRa and – b with Hv-FGF-f (shown in S4, Plate II by a double labeling), we cannot exclude that Hydra FGFs act on a short range or even within the cells. This will be discussed in the following, mainly with respect to the Hydra head.

Hydra FGFs are expressed strongly in restricted domains and might act at short distances or even intracellular

Locally upregulated expression in testis, terminal and/or boundary regions is a hallmark of the FGFs analysed here and in previously studies (Krishnapati and Ghaskadbi, 2013, Lange et al., 2014).

FGF-j and FGF-i

The two genomic neighbors in the Hydra T2T_105 genome, Hv-fgf-i and Hv-fgf-j are both expressed in the extreme tentacle tips of Hydra AEP - however in different tissue layers: Hv-fgf-i in ectodermal and FGF-j in endodermal epithelial cells. Both proteins are closely related, with a similar pI of 9,6 and 9,3 and a low probability for a signal peptide (53,2 % for FGF-i, 30,6% for FGF-j). It is likely that they were generated by a duplication, but what is their potential function in this tissue? Tentacle tip cells are terminally differentiated and strongly bent to keep the tissue closed even if wiggling prey is fixed. They are thus in a very exposed and mechanically stressed position. Tentacle tip cells are sloughed off eventually without disturbing the integrity of the tentacle. A local FGF function might therefore be in cell physiology or by acting on a short range, e.g. enabling the woundless detachment of cells at the tip. This hypothesis fits with the FGFR-dependent smooth detachment of cells from adjacent ones when bud and parent separate (Hasse et al., 2014; Holz et al., 2017). Another function might be prevention of apoptosis which is a main function of vertebrate FGF2 and FGF8 (Katoh and Nakagama, 2014). Apoptotic cells occur frequently along the tentacles as shown by Tunel analysis, but they are rare in the tentacle tips (Chera et al., 2009). However, both genes are not expressed in the testes where apoptosis occurs frequently and mostly basal where stem cells enter the testis (Kuznetsov et al., 2001). FGF-f, FGF-h and FGF-k are expressed in basal and apical positions or across the whole testis.

Whether FGF-j and FGF-i exert similar (non)redundant functions in the ecto- and endoderm of Hydra remains an interesting question particularly with respect to their genomic neighborship in Hydra magnipapillata wt 105 and their separation in the Hydra AEP genome.

FGF-b

A second typical example for local transcription is Hv-fgf-b in endodermal tentacle cells and in just 10-12 cells at the foot pore. FGF-b is identical to FGF1 (t12060-AEP, gene ID G005481, 688 nucleotides) which was identified in the Hydra 2.0 Genome Project Portal as endodermal tentacle and basal disc gene (Siebert et al., 2019). The overall expression pattern is congruent. Our study now adds a detailed spatial resolution like presence of FGF-b positive stenotele and desmonemes nematocytes in the tentacle endoderm.

The Hydra endoderm contains only degenerating nematocytes engulfed by endodermal processes and phagocytosed (Lyon et al., 1982). The FGF-b positive huge stenotele nematocyte-like cells had no visible capsule or thread-structure, but their size and shape with the stained cytoplasm in a peripheral position suggests that they are degenerating stenotele nematocytes as described in the 1980s using ultrastructural methods. Function of the FGFb in these degenerating, but not in the functional ectodermal nematocytes is obscure. Vertebrate FGFs prevent apoptosis, induce proliferation, control cell shape, their migration or differentiation (Ornitz and Itoh, 2022; Katoh and Nakagama, 2014). None of these functions seems relevant for degenerating nematocytes.

We were unable to track an FGF-b function for morphogenesis by siRNA knockdown. Given the reliability of the siRNA knockdown for Hv-fgfra and Hv-FGF-c, we propose to consider localized, cell type-specific (physiological) function(s) for FGF-b in the terminally differentiated tentacle and foot pore cells. Hv-FGF-b lacks a signal sequence. Although there are alternative secretion mechanisms for FGFs (Ornitz and Itoh, 2022; Biadun et al., 2024), Hv-FGF-b, is a potential candidate as intracellular FGF. In vertebrates, FGFs 11-14 fail to bind FGFR and act intracellular in excitable cells like neurons and cardiomyocytes where they modulate voltage-gated sodium channels and calcium-induced calcium release (Hennessey et al., 2013). The tentacle endoderm lacks neurons according to recent investigations (Keramidioti et al., 2024) and channel modulating activities in epithelial cells are therefore an interesting aspect. Although the ectodermal neurons and battery-epitheliomuscle cells are sufficient to induce tentacle contractions (the ectodermal myonemes run longitudinally), an autonomous endodermal epithelial excitability would be helpful to support tentacle elongation and movement. Endodermal epitheliomuscle cells constrict the circumference and elongate the Hydra body.

A si_Hv-fgf-c knockdown evokes battery cell nodules

The third FGF example to discuss, Hv-fgf-c is interesting as a morphogenesis controlling growth factor. Hv-fgf-c mRNA is upregulated in a ring around the basal disc and in a few ectodermal cells at the tentacles bases which seem to be connected to each other, resembling a chain. Their position is strategic, because actively migrating cells coming in from the body column have to pass this region and must receive signals to terminally differentiate and reach their target position in the battery cells.

The siRNA of Hv-fgf-c did not affect the foot region morphologically, but evoked a striking tentacle phenotype: tentacles developed nodules, from day five after siRNA electroporation. This corresponds to about the time of the maximal siRNA effect in Hydra (Lommel et al., 2017). In nodules the endoderm was bloated and the ectodermal battery cells were tightly clustered on the outside and equipped abundantly with a chaotic arrangement of, mostly, stenotele nematocytes. A milder phenotype occurred flanking to bloated regions: here, the nematocyte charge of battery cells appeared irregular, but the distance to neighboring cells or the nodule was kept.

The results suggest that Hydra FGFc is involved in the regulation of arrangement and / or equipment of battery cells, particularly with respect to stenoteles. FGFc might control the canonical pattern within a battery cell with 1-2 huge central stenoteles and surrounding small desmonemes as well as isorhiza. This pattern determines the battery cell shape. Central stenoteles raise battery cells in the middle and the surrounding smaller nematocytes allow a flattening towards adjacent battery cells. Empty battery cells at the tentacle base or deprived of nematocytes are flat and the tentacles appear smooth. As a first simple hypothesis, we propose that battery cell positions along the tentacles are unchanged and cell-to-cell contacts developed in their normal way.

Nematocytes integrate in battery cell pouches (Novak and Wood, 1983), and tightly anchor in the mesoglea. If too many stenoteles integrate in adjacent battery cells their shape would change. Provided, the tissue has a limited flexibility, an overload with stenoteles in adjacent battery cells would raise the cells and compact them closely resembling a cluster. Nodules are the result when the signal for stenotele immigration is too strong for a limited time span.

FGFc is, therewith, a candidate to control stenotele nematocyte distribution to battery cells.

The FGF-c knockdown tentacle phenotype is not obtained by an FGFR knockdown and occurs strain specific

Although the FGF-c knockdown phenotype is striking and mechanistically interesting, there are two obvious problems. First, the FGFc knockdown phenotype is not obtained by a knockdown of Hydra FGFRa. Both FGFRa (Kringelchen) as well as the slightly divergent FGFRb are co-expressed weakly throughout the body column, but upregulated only during budding at the constriction and detachment site and in early tentacle development (Supplement Fig. S4; Sudhop et al., 2004; Suryawanshi et al., 2020). This does not exclude an FGF/FGFR interaction in low expression regions like at the mature tentacles, but 54% probability for a signal sequence is poor and release of FGFc from tentacle base cells questionable. To affect e.g. stenotele immigration or battery cell load a diffusible signal even on short distance is a most likely mechanism.

Second, the phenotype was strain-specific - obtained in the Hydra AEP traffic light line (Wang et al., 2022) only and not in Hydra vulgaris AEP. As one possibility to explain this discrepancy we consider its genotype. Hydra AEP traffic light was generated in several steps from chimaera of Hydra vulgaris AEP water melon and Hydra magnipapillata A10 (Wang et al., 2022). A10 is a hybrid between the wild type Hydra magnipapillata wt 105 and nematocytes of H. magnipapillata sf1, a mutant with temperature-sensitive i-cells, generated by transplantation of interstitial cells to epithelial wild type Hydra (Kasahara and Bosch, 2003). These I-cells were first introduced and then removed using colchicine in the steps to generate the tricolor Traffic light Hydra. It cannot be excluded that a few very slow cycling A10 stem cells survived this process and persist in Hydra AEP traffic light - now allowing for effects not seen in Hydra AEP. As well, the insertion of the YPet construct in Hydra AEP ss1 used to generate the Traffic Light ectoderm is a factor which might be responsible for the susceptibility of Hydra AEP Traffic light to the FGF-c knockdown.

As a third possibility, we have to discuss potential off-target effects of the Hv-fgf-c knockdown in Hydra AEP Traffic Light. Both Hv-fgf-c siRNAs were selected carefully by (i) using the suggestions of Kaneka Eurogentec for optimal siRNAs and (ii) controlling these sequences against the Hydra nucleotide databases to avoid interference with other genes. This approach sometimes requires a trade-off, because the best-suited siRNA sequences might not be appropriate. In the case of Hv-fgf-c, siHv-fgf-c_1 was designed, as usual, for a sequence close to the 5’end. For a second siRNA, no reasonable match was possible within the coding sequence. We instead had to use for siHv-fgf-c_2 a sequence in the 3’UTR of the mRNA. Since this siRNA yielded an identical tentacle phenotype, although at a lower incidence, we consider an off- target effect to be unlikely.

Although the strong effect (tentacle nodules) is strain-specific, the basal ability to react on the Hv-fgf-c knockdown and therewith FGF-c signals altering tentacle morphology and cell composition is obviously present in both, Hydra AEP as well as Hydra AEP Traffic light. In summary, despite some puzzling results, the whole set of Hydra FGFs shows very interesting features and expression patterns for future investigations. Elucidating the role of this ancestral signaling system in the “simple” fresh water polyp Hydra remains a fascinating task.

Conclusion

Processes like the constant cell proliferation, directional cell migration and tissue morphogenesis occur in the prebilaterian Hydra as in Bilateria, but whether the signaling systems involved act in a similar way is only partially answered. In particular, the functions of the many elements of the Hydra FGF/R signaling system are still unknown. Our investigation revealed an unexpected number of Hydra FGFs and shed some light on the function of Hv-FGFc, but as well raised new questions. The differential upregulation of all 15 Hydra FGFs in defined domains of the polyp suggests specialized and, in some cases, local or even intracellular functions. For FGFc a function was tracked to the establishment of the stereotypic pattern of battery cell and their stinging cells along the tentacles. However, the fact that battery cell clusters and tentacle nodules were observed only in one Hydra AEP strain which was established by using three different Hydra strains as transplant donors or intermediate transplant acceptors indicates a potentially complex genotypic situation which has to be investigated to elucidate the mechanism of this FGF. Whether Hydra FGFs act in a way comparable to bilaterian FGFs in attracting other cells and controlling tissue movement remain very interesting questions given the lack of a canonical signal sequence in two thirds of them. The answer(s) will help to obtain a conclusive picture of prebilaterian FGF functions.

Materials and Methods

Hydra culture and manipulation

The Traffic light strain of Hydra AEP was obtained from Eva Collins, Swarthmore College, formerly UC San Diego (Wang et al., 2022). Hydra vulgaris AEP was obtained from Thomas Bosch, Kiel and both were cultured in hydra medium (HM) under standard conditions (Klimovich et al., 2019). All manipulations of Hydra were done with polyps unfed for at least 24 hrs.

Grafting and relaxation

60 mm Petri dishes were prepared for grafting by pouring 2-3 ml melted paraffin into a 45° tilted dish and placing a 0.1 mm insect needle head down in the soft paraffin at an angle of 20 - 30° during the hardening process. Small silicon cushions (2 x 2 mm) were prepared from silicon tubing and pierced in the middle using an injection cannula. One cushion was immediately transferred to the insect needle and later fixed the first transplant on one side. The grafting dish was filled with HM until the tip of the needle was well submerged. One transgenic and one non-transgenic animal were relaxed in 1 mM linalool in HM for 10 min (Goel et al., 2019) and bisected in 100 mm dishes. The parts of interest were transferred to the grafting dish and transplanted within a maximum of 3 min after bisection. All manipulations were done using a Dumont No 5 forceps (ROTH 10427301). The head of a recipient animal was placed on the insect needle with its hypostome towards and close to the silicon cushion. Then the open body column of the lower part of a donor was forced on the needle and the transplant slightly pressed together by a second silicon cushion. Transplants were removed from the needle after 2 hrs.

Imaging

All pictures of living Hydra were taken within 10 min following about 10 min relaxation in 1 mM Linalool/HM. Tentacle pictures should be taken as fast as possible, otherwise the battery cells flatten and are difficult to evaluate. Single polyps were transferred to a slide in 100 μl linalool/HM and overlayed by a 2 x 2 cm sheet of cellophane. This way polyps can be flipped and pictures taken from both sides for about 10 min. Thereafter, polyps were transferred to a petri dish with hydra medium and washed twice for 5 min each. Fixed polyps were prepared following standard procedures (Klimovich et al., 2019) and embedded permanently in Roti®Mount FluorCare. GFP and dsRED fluorescence were monitored on the Nikon TS2000 Eclipse fluorescence or as cLSM on a LeicaTCSSP5 microscope.

Genomic databases

We analysed the genomic distribution of the 15 Hydra FGFs in the genomic libraries of two Hydra strains, Hydra T2T_105 versus Hydra T2T_AEP (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/genome/GCF_037890685.1; 25.7.2025). Both were generated from the haplotype of a Hydra magnipapillata wt 105/Hydra vulgaris AEP hybrid by chromosome scale telomere to telomere assemblies. Data were derived using BLAST of the cDNA sequences and the Genome Data Viewer to retrieve features and ranges of the genes (see Supplement S3). Further data like accession numbers for nucleotide sequences and proteins are available using the Genome Data Viewer.

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization and controls were carried out as previously described (Suryawanshi et al., 2020). The Hv-fgf and Hv-fgfr-a, Hv-fgfr-b (anti)sense probes were diluted after synthesis by a factor of 1:10 for a first attempt and up to 1:20.000 to optimize the results. As an example, for hv-fgf-b, the probe was diluted 1:1000 and staining time was reduced to 5-10 min for a sensitive detection of Hv-fgf-b neurons, but to detect the positive cells close to the foot pore, staining was prolonged to 1,5 hrs (or probe used 1:100) and stopped with 1x TE buffer, pH 7,5. Additional to previously published methods, background staining was reduced by changing from 1x TE to 100% MeOH in 3 steps (75:25, 50:50, 25:75) and immersing for a maximum of 30 min in 100 % MeOH followed by rehydration in three steps to 1x PBS and a post-fixation step in 4% paraformaldehyde / 1x PBS for 30 min. Double in situ hybridization was performed according to (Hansen et al., 2000). In situ hybridization to single cell preparations as described (Hassel, 1998).

siRNA-mediated knockdown in Hydra

Appropriate siRNA sequences were proposed for each cDNA sequence by Kaneka Eurogentec and controlled by us blasting against the Hydra EST database to avoid cross reactions (sequences in Table 1). Usually, two siRNAs are placed close to the 5’ end. If no second appropriate sequence was identified a proposed sequence close to the 3’ end was chosen. Custom made RP-HPLC siRNA-duplexes were ordered as HPLC-purified, lyophilized siRNA and stored at -80°C.

Table 1

siRNA Hv-fgf-b, Hv-fgf-c and fgfr_1

| siRNA | Sequence 5‘ à 3‘ | Nucleotides covered on mRNA starting at AUG |

|---|---|---|

| fgfc_1 | 5’ GUUCAGAGAACACCUGAAA dTdT 5’ UUUCAGGUGUUCUCUGAAC dTdT |

121 - 139 |

| fgfc_2 | 5’ CCAAUAUCAAACCGACUAU dTdT 5’ AUAGUCGGUUUGAUAUUGG dTdT |

651 – 669 (noncoding 3‘ end; weak effect) |

| fgfb_1 | 5’ CCUAACUCAUGGUAUCUAU dTdT 5’ AUAGAUACCAUGAGUUAGG dTdT |

73 - 91 |

| fgfb_2 | 5’ CCAACCUUGAUGCCAAGAA dTdT 5’ UUCUUGGCAUCAAGGUUGG dTdT |

298 - 316 |

| fgfra_1 | 5’ CAGAGCCAGUUAAUUAUAU dTdT 5’ AUAUAAUUAACUGGCUCUG dTdT |

68 – 86 (no second siRNA effective) |

| pGL2 luciferase (firefly) negative control siRNA | 5’ CGUACGCGGAAUACUUCGA dTdT 5’ UCGAAGUAUUCCGCGUACG dTdT |

(Elbashir et al. 2001) |

Electroporation was performed according to Lommel et al., 2017 in triplicates of ten Hydra polyps each, unfed for 24 hrs. Budless polyps were used for Hydra fgf and pGL2/scrGFP siRNAs, while Hv-fgfr-a siRNA was applied to polyps carrying stage 3 buds to evoke the branching phenotype as positive control (Sudhop et al., 2004). Immediately prior to use the siRNAs were suspended in water. We either used 3 µM siRNA in 100 μl DEPC-treated, autoclaved MilliQ water for a single siRNA to be electroporated (fgfra_1 or scrGFP or pGL2 and the FGF siRNAs in preparatory experiments) or a total of 4 µM siRNA in 100 μl sterile water when two siRNAs were used at 2 µM each (fgfc_1 and fgfc_2 or fgfb_1 and fgfb_2). Electroporation was at 250 V, 25 ms using a square pulse (Fischer, Heidelberg, Square pulser (prototype 1998); 4 mm PeqLab or BioRad electroporation cuvettes). Polyps were handled very careful following electroporation, avoiding shearing by air bubbles or a strong liquid stream. 48 hours post electroporation Hydra had regenerated short to medium length tentacles. They were fed and carefully cleaned prior to two days starvation. Unless otherwise indicated, the polyps were fed 5 times a week thereafter and their morphology was analysed and documented prior to feeding.

Cloning of the Hv-fgf cDNA using the expression vector pcDNA3.1 myc-His A

The Hv-fgf cDNAs were amplified via PCR with specific oligonucleotide primers (Table 2) and ligated in the expression vector pcDNA3.1-myc-His A. This vector is suitable for mammalian cell culture systems and adds a C-terminal polyhistidine-tag plus a myc-tag to the translated protein. Both enable purification and detection of the protein of interest.

Table 2

Primers used to amplify and clone the Hv-fgf cDNA into the vector pcDNATM3.1 myc-His A

| Name | Sequence 5’ to 3’ | Length [bp] | TM [°C] |

|---|---|---|---|

| FGFb fw | GG CCC GAA TTC AAA ATG ATA TTG CTT CAA AGT TTT TTT G | 39 | 58 |

| FGFb rv | CTC GAG TGC TTT CTG CTT TTT TCC ACC | 27 | 64 |

| FGFc fw | GG CCC GAA TTC AAC ATG AAG TTC TAC TTT TTA GTG TTT C | 39 | 58 |

| FGFc rv | CTC GAG TCT TCG GAT GCA CAG TTG ATC | 27 | 65 |

| FGFe fw | GG CCC GAA TTC ACG ATG TTG ATG AAC CTA TTT TTT CTC | 38 | 58 |

| FGFe rv | CTC GAG ACG AAT CGT TGA TAA TGG TTG G | 28 | 63 |

| FGFf fw | GG CCC GAA TTC AAA ATG ATT CGA ATG AAT GGT TTA AAA CG | 40 | 62 |

| FGFf rv | CTC GAG ATT TTT TTT TAA ATT TTC CAA TTT CAT C | 34 | 55 |

The coding sequences for Hydra vulgaris fgf-b, fgf-c, fgf-e, and fgf-f were amplified by PCR with Q5-polymerase (NEB, USA) under the following conditions: 5 min initial denaturation (98°C) followed by 35 cycles: 1 min denaturation at 98°C, 1 min annealing (fgf-b, fgf-c, fgf-e: 58°C; fgf-f: 56°C, 1 min elongation at 72°C; 10 min final elongation at 72°C and cooling/storage at 4°C. During PCR, the 5’ EcoRI and 3’ XhoI restriction recognition sites (underlined in Table 2) were incorporated via primer extension. The amplified inserts as well as the expression vector were double digested with EcoRI and XhoI under standard conditions and the opened vector was dephosphorylated with Antarctic Phosphatase (NEB) to avoid self-ligation. Ligation was performed with T4 Ligase (NEB) and the construct transformed into chemically competent cells of the Escherichia coli strain DH5α. Positive transformants were selected on Ampicillin containing Luria-Bertani (LB) agarose and the insert-containing plasmid DNA sequenced by Microsynth AG (Switzerland). The constructs were kept in DH5α for selection, amplification, and storage.

HEK293T cell culture and transfection

HEK293T cells are adherent cells. They were cultured in 10 ml Dulbeccos Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco) with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin-streptomycin (100 U penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin) in 75 cm2 flasks at 37 °C and 5 % CO2. For transfection, cells were grown in 6-well plates to a concentration of 5 x 106 cells in 2 ml DMEM. The medium was replaced by 400 µl of fresh medium. For transfection, 2.5 µg plasmid DNA per Hv-fgf construct were mixed with 100 µl opti-MEM and 4 µl Lipofectamine (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and preincubated at room temperature for 15 min. The transfection mix was added to the cells for 6 hrs and thereafter diluted with 1 ml of fresh medium. Further incubation for up to four days followed at 37 °C and 5 % CO2.

Cell harvest and determination of optimal protein expression in HEK293T

After protein expression, the cell culture medium was collected and centrifuged for 5 min at 3000 x g to remove any remaining cells. Aliquots of the supernatant were stored at – 20 °C for later analysis. The adhesive cells were treated with TrypLETM (Thermo Fisher) for 1 min at 37 °C and 5 % CO2. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 2 ml fresh DMEM, the cell suspension transferred to reaction tubes and centrifuged for 5 min at 3000 x g. The supernatant was removed and 150 µl of lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.5 % (v/v) Triton X-100 (NP-40) and cOmpleteTM Mini protease inhibitor cocktail (Merck) was added. The pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer and stored at – 20 °C until Western Blot analysis.

The time of maximum Hv-FGF expression was determined using four individual wells of a 6 well plate per transfected Hv-FGF. Cells of one well, each, were harvested at 24, 48, 72 and 96 hours post transfection (hpt) and supernatant and cell lysate were analyzed via dot blot. To this end 2 μl of each cell lysate and supernatant sample were dotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane and dried for 1 h at room temperature (RT). The membrane was blocked with 5 % casein in 1 x TBS-T (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20) for 30 min at RT. Detection of the recombinant proteins by primary anti-myc antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, diluted 1:100 in blocking buffer) occurred for 30 min at RT. The membrane was washed 3 x 5 min with PBTx (1x PBS, 0.25% Triton-X 100) and incubated with the secondary HRP conjugated anti-mouse antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific, diluted 1:100 in blocking buffer) for 30 min, RT. The antibody was removed by washing 3 x 5 min with PBTx, followed by an additional washing step in sterile H2O. Detection of the antibody signal was performed via ECL in a LI-COR Odyssey FC.

Purification of FGFe and FGF-f by Nickel-NTA affinity chromatography

HEK293T cells were grown in 75 cm2 flasks to a concentration of 5 x 106 cells in 20 ml DMEM. Before transfection, the medium was removed and replaced with 4 ml of fresh medium. 8 μg plasmid DNA was mixed with 1 ml opti-MEM and 30 μl lipofectamine and incubated at room temperature for 15 min. After addition of the transfection mix the cells were placed in the incubator for at least 6 hrs before 10 ml medium was added for incubation at 37 °C, 5 % CO2 for 72 hrs. The medium was removed from the cells, centrifuged for 5 min. at 3000xg and the supernatant stored in a fresh reaction tube at -20 °C until further analysis. The cells were treated with TrypLETM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 min at 37 °C, 5 % CO2 and the reaction stopped by addition of 20 ml fresh DMEM. The cells were transferred into a fresh reaction tube and centrifuged for 5 min. at 3000xg. The supernatant was discarded and the cells were resuspended in 1,5 ml lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 % (v/v) Triton X-100 and cOmpleteTM Mini protease inhibitor cocktail (Merck)).

Purification of the histidine-tagged FGFs was performed by immobilized metal affinity chromatography with Ni-NTA sepharose under native conditions as recommended by the manufacturer (QIAGEN). A 1,5 ml Ni-NTA sepharose column was prepared and washed once with 6 ml sterile H2O and equilibrated twice with 6 ml native binding buffer (250 mM NaH2PO4 pH 8.0, 2.5 M NaCl). 1.5 ml cell lysate was diluted with 8 ml native binding buffer. The sample was pressed through an 18 gauge needle to reduce viscosity. The sample was centrifuged for 15 min, 3000xg, 4 °C, transferred to a fresh reaction tube and mixed with the prepared Ni-NTA Sepharose. Protein binding to the resin followed on a platform shaker (60 min, 125 rpm, 4 °C). The column was washed 5 x with 8 ml native washing buffer (250 mM NaH2PO4, pH 8.0, 2.5 M NaCl, 20 mM imidazole). The proteins were eluted with 8 ml native elution buffer (250 mM NaH2PO4, pH 8.0, 2.5 M NaCl, 250 mM imidazole). The eluate was collected in 1 ml fractions and stored at 4 °C until dot blot analysis.

Immunodetection in HEK293T cells

To detect the expression of the recombinant Hydra vulgaris AEP FGFs, transfected HEK293T cells were grown on coverslips and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/ 1x PBS and the proteins detected via the attached myc-tag. The mouse anti-myc antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was diluted 1:100 in 1x PBS and detected with anti-mouse Alexa Fluor488 secondary antibody (BioLegend, diluted 1:500 in PBS). As a control, untransfected HEK293T cells were analysed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Rob Steele and David Miller for their helpful comments on a previous version of the manuscript and Charles David and Celina Juliano for informations on tentacle neurons. We thank Eva-Maria Collins and Rui Wang for the Traffic light Hydra and Thomas Bosch for Hydra AEP. Sabrina Voswinkel and Paul Schmitt took expert animal care. Our highly motivated BSc and MSc students Katja Adamkiewicz, Maren Schmandt and Marcel Schöpe participated in developing and testing appropriate methods for apical Hydra tissue shift (K.A.) and siRNA experiments.

Abbreviations

BSA, bovine serum albumin ; cDNA, complementary DNA ; dpt, days post transplantation ; dpe, days post electroporation ; ECL, enhanced chemiluminescence ; FGF, fibroblast growth factor ; FGFR, fibroblast growth factor receptor ; GFP, green fluorescent protein ; HEK, human embryonic kidney ; His-tag, polyhistidine-tag ; HM, hydra medium ; hpe, hours post electroporation ; hpi, hours post induction ; hpt, hours post transfection ; kDa, kilo Dalton ; Ni-NTA, nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid ; nt, nucleotide ; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline ; pI, isoelectric point ; siRNA, small interfering RNA ;Declarations

Author contributions

KO identified and cloned the ten new FGFs for further analysis, evaluated the protein properties, subcloned all FGFs for eukaryotic expression, established the HEK cell culture together with SÖ and took first steps to purify the FGFs. ISH analyses were carried out by KO, LR and MH. The siRNA experiments were planned, optimized, carried out and evaluated by LK, LR, KO and MH. All authors contributed in writing the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The Authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Experimentation with animals

All works carried out with animals (Hydra) comply with the ethical standards of the German and international institutions.

References

Aufschnaiter R., Zamir E. A., Little C. D., Özbek S., Münder S., David C. N., Li L., Sarras M. P., Zhang X. (2011). In vivo imaging of basement membrane movement: ECM patterning shapes Hydra polyps. Journal of Cell Science 124: 4027-4038.

Bertrand S., Iwema T., Escriva H. (2014). FGF Signaling Emerged Concomitantly with the Origin of Eumetazoans. Molecular Biology and Evolution 31: 310-318.

Biadun M., Sochacka M., Kalka M., Chorazewska A., Karelus R., Krowarsch D., Opalinski L., Zakrzewska M. (2024). Uncovering key steps in FGF12 cellular release reveals a common mechanism for unconventional FGF protein secretion. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 81: 356.

Campbell R. D. (1967). Tissue dynamics of steady state growth in Hydra littoralis. Developmental Biology 15: 487-502.

Cebrià F., Kobayashi C., Umesono Y., Nakazawa M., Mineta K., Ikeo K., Gojobori T., Itoh M., Taira M., Alvarado A. S., Agata K. (2002). FGFR-related gene nou-darake restricts brain tissues to the head region of planarians. Nature 419: 620-624.

Chera S., Ghila L., Dobretz K., Wenger Y., Bauer C., Buzgariu W., Martinou J.C., Galliot B. (2009). Apoptotic Cells Provide an Unexpected Source of Wnt3 Signaling to Drive Hydra Head Regeneration. Developmental Cell 17: 279-289.

Dossenbach C., Röck S., Affolter M. (2001). Specificity of FGF signaling in cell migration in Drosophila. Development 128: 4563-4572.

Elbashir S. M., Harborth J., Lendeckel W., Yalcin A., Weber K., Tuschl T. (2001). Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature 411: 494-498.

Gibbs H. C., Chang-Gonzalez A., Hwang W., Yeh A. T., Lekven A. C. (2017). Midbrain-Hindbrain Boundary Morphogenesis: At the Intersection of Wnt and Fgf Signaling. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy 11: 64.

Goel T., Wang R., Martin S., Lanphear E., Collins E.M. S. (2019). Linalool acts as a fast and reversible anesthetic in Hydra. PLOS ONE 14: e0224221.

Hansen G. N., Williamson M., Grimmelikhuijzen C. J. P. (2000). Two-color double-labeling in situ hybridization of whole-mount Hydra using RNA probes for five different Hydra neuropeptide preprohormones: evidence for colocalization. Cell and Tissue Research 301: 245-253.

Hasse C., Holz O., Lange E., Pisowodzki L., Rebscher N., Christin Eder M., Hobmayer B., Hassel M. (2014). FGFR-ERK signaling is an essential component of tissue separation. Developmental Biology 395: 154-166.

Hassel M. (1998). Upregulation of a Hydra vulgaris cPKC gene is tightly coupled to the differentiation of head structures. Development Genes and Evolution 207: 489-501.

Hennessey J. A., Wei E. Q., Pitt G. S. (2013). Fibroblast Growth Factor Homologous Factors Modulate Cardiac Calcium Channels. Circulation Research 113: 381-388.

Hobmayer B., Jenewein M., Eder D., Eder M.K., Glasauer S., Gufler S., Hartl M., Salvenmoser W. (2012). Stemness in Hydra - a current perspective. The International Journal of Developmental Biology 56: 509-517.

Holstein T. W. (2023). The Hydra stem cell system – Revisited. Cells & Development 174: 203846.

Holz O., Apel D., Hassel M. (2020). Alternative pathways control actomyosin contractility in epitheliomuscle cells during morphogenesis and body contraction. Developmental Biology 463: 88-98.

Holz O., Apel D., Steinmetz P., Lange E., Hopfenmüller S., Ohler K., Sudhop S., Hassel M. (2017). Bud detachment in hydra requires activation of fibroblast growth factor receptor and a Rho–ROCK–myosin II signaling pathway to ensure formation of a basal constriction. Developmental Dynamics 246: 502-516.

Itoh N., Ornitz D. M. (2004). Evolution of the Fgf and Fgfr gene families. Trends in Genetics 20: 563-569.

Kasahara S., Bosch T. C.G. (2003). Enhanced antibacterial activity in Hydra polyps lacking nerve cells. Developmental & Comparative Immunology 27: 79-85.

Katoh M., Nakagama H. (2014). FGF Receptors: Cancer Biology and Therapeutics. Medicinal Research Reviews 34: 280-300.

Keramidioti A., Schneid S., Busse C., Cramer von Laue C., Bertulat B., Salvenmoser W., Hess M., Alexandrova O., Glauber K. M., Steele R. E., Hobmayer B., Holstein T. W., David C. N. (2024). A new look at the architecture and dynamics of the Hydra nerve net. eLife 12: RP87330.

Klimovich A., Wittlieb J., Bosch T. C. G. (2019). Transgenesis in Hydra to characterize gene function and visualize cell behavior. Nature Protocols 14: 2069-2090.

Krishnapati L.S., Ghaskadbi S. (2013). Identification and characterization of VEGF and FGF from Hydra. The International Journal of Developmental Biology 57: 897-906.

Kuznetsov S., Lyanguzowa M., Bosch T. C.G. (2001). Role of epithelial cells and programmed cell death in Hydra spermatogenesis. Zoology 104: 25-31.

Lange E., Bertrand S., Holz O., Rebscher N., Hassel M. (2014). Dynamic expression of a Hydra FGF at boundaries and termini. Development Genes and Evolution 224: 235-244.

Lengfeld T., Watanabe H., Simakov O., Lindgens D., Gee L., Law L., Schmidt H. A., Özbek S., Bode H., Holstein T. W. (2009). Multiple Wnts are involved in Hydra organizer formation and regeneration. Developmental Biology 330: 186-199.

Lommel M., Tursch A., Rustarazo-Calvo L., Trageser B., Holstein T., (2017). Genetic knockdown and knockout approaches in Hydra. BioRxiv Preprint: .

Lyon M.K., Kass-Simon G., Hufnagel L.A. (1982). Ultrastructural analysis of nematocyte removal in Hydra. Tissue and Cell 14: 415-424.

Matus D. Q., Thomsen G. H., Martindale M. Q. (2007). FGF signaling in gastrulation and neural development in Nematostella vectensis, an anthozoan cnidarian. Development Genes and Evolution 217: 137-148.

Miyakawa K., Imamura T. (2003). Secretion of FGF-16 Requires an Uncleaved Bipartite Signal Sequence. Journal of Biological Chemistry 278: 35718-35724.

Mohammadi M., Olsen S. K., Ibrahimi O. A. (2005). Structural basis for fibroblast growth factor receptor activation. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews 16: 107-137.

Münder S., Käsbauer T., Prexl A., Aufschnaiter R., Zhang X., Towb P., Böttger A. (2010). Notch signalling defines critical boundary during budding in Hydra. Developmental Biology 344: 331-345.

Nechiporuk A., Raible D. W. (2008). FGF-Dependent Mechanosensory Organ Patterning in Zebrafish. Science 320: 1774-1777.

Novak P. L., Wood R. L. (1983). Development of the nematocyte junctional complex in hydra tentacles in relation to cellular recognition and positioning. Journal of Ultrastructure Research 83: 111-121.

Ohuchi H., Nakagawa T., Yamamoto A., Araga A., Ohata T., Ishimaru Y., Yoshioka H., Kuwana T., Nohno T., Yamasaki M., Itoh N., Noji S. (1997). The mesenchymal factor, FGF10, initiates and maintains the outgrowth of the chick limb bud through interaction with FGF8, an apical ectodermal factor. Development 124: 2235-2244.

Ornitz D. M., Itoh N. (2022). New developments in the biology of fibroblast growth factors. WIREs Mechanisms of Disease 14: e1549.

Rebscher N., Deichmann C., Sudhop S., Fritzenwanker J. H., Green S., Hassel M. (2009). Conserved intron positions in FGFR genes reflect the modular structure of FGFR and reveal stepwise addition of domains to an already complex ancestral FGFR. Development Genes and Evolution 219: 455-468.

Rentzsch F., Fritzenwanker J. H., Scholz C. B., Technau U. (2008). FGF signalling controls formation of the apical sensory organ in the cnidarian Nematostella vectensis. Development 135: 1761-1769.

Rothenbusch-Fender S., Fritzen K., Bischoff M. C., Buttgereit D., Oenel S. F., Renkawitz-Pohl R. (2017). Myotube migration to cover and shape the testis of Drosophila depends on Heartless, Cadherin/Catenin, and myosin II. Biology Open 6: 18761888.

Rudolf A., Hübinger C., Hüsken K., Vogt A., Rebscher N., Önel S.F., Renkawitz-Pohl R., Hassel M. (2013). The Hydra FGFR, Kringelchen, partially replaces the Drosophila Heartless FGFR. Development Genes and Evolution 223: 159-169.

Sabin K. Z., Chen S., Hill E. M., Weaver K. J., Yonke J., Kirkman M.E., Redwine W. B., Klompen A. M.L., Zhao X., Guo F., McKinney M. C., Dewey J. L., Gibson M. C. (2024). Graded FGF activity patterns distinct cell types within the apical sensory organ of the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis. Developmental Biology 510: 50-65.

Seabra S., Zenleser T., Grosbusch A. L., Hobmayer B., Lengerer B. (2022). The Involvement of Cell-Type-Specific Glycans in Hydra Temporary Adhesion Revealed by a Lectin Screen. Biomimetics 7: 166.

Shimizu H., Aufschnaiter R., Li L., Sarras M. P., Borza D.B., Abrahamson D. R., Sado Y., Zhang X. (2008). The extracellular matrix of hydra is a porous sheet and contains type IV collagen. Zoology 111: 410-418.

Siebert S., Farrell J. A., Cazet J. F., Abeykoon Y., Primack A. S., Schnitzler C. E., Juliano C. E. (2019). Stem cell differentiation trajectories in Hydra resolved at single-cell resolution. Science 365: eaav9314.

Stathopoulos A., Tam B., Ronshaugen M., Frasch M., Levine M. (2004). pyramus and thisbe: FGF genes that pattern the mesoderm of Drosophila embryos. Genes & Development 18: 687-699.

Sudhop S., Coulier F., Bieller A., Vogt A., Hotz T., Hassel M. (2004). Signalling by the FGFR-like tyrosine kinase, Kringelchen, is essential for bud detachment in Hydra vulgaris. Development 131: 4001-4011.

Suryawanshi A., Schaefer K., Holz O., Apel D., Lange E., Hayward D. C., Miller D. J., Hassel M. (2020). What lies beneath: Hydra provides cnidarian perspectives into the evolution of FGFR docking proteins. Development Genes and Evolution 230: 227-238.

Technau U., (2020). Gastrulation and germ layer formation in the sea anemone Nematostella vectensis and other cnidarians. Mechanisms of Development 163: 103628.

Vogg M. C., Beccari L., Iglesias Ollé L., Rampon C., Vriz S., Perruchoud C., Wenger Y., Galliot B. (2019). An evolutionarily-conserved Wnt3/β-catenin/Sp5 feedback loop restricts head organizer activity in Hydra. Nature Communications 10: 312.

Wang R., DuBuc T. Q., Steele R. E., Collins E.M. S. (2022). Traffic light Hydra allows for simultaneous in vivo imaging of all three cell lineages. Developmental Biology 488: 74-80.