Int. J. Dev. Biol. 69: 151 - 158 (2025)

Osteogenic gene expression in the temporal region of the opossum embryos: an insight into the evolution of synapsid skull unique to mammalian lineage

Open Access | Developmental Expression Pattern | Published: 19 November 2025

Abstract

The skull of amniotes is categorized into three conditions based on skeletal arrangement in the temporal region: anapsid, synapsid and diapsid. Mammals (class Mammalia), a descendent lineage of the clade Synapsida, possess the synapsid skull, which is characterized by a single lower temporal arch that ventrally borders the lower temporal fenestra. Although we previously suggested, based on the data from placental mammals, that the reduction in the expression domain of the upstream osteogenic genes Msx2 and Runx2 in the embryonic temporal mesenchyme might have played a role in the evolution of synapsid skulls, the molecular basis of synapsid skull evolution is still largely unknown. In this study, we investigated expression patterns of four osteogenic genes (two upstream genes Msx2 and Runx2 and two downstream genes Sp7 and Sparc) in the embryonic and neonatal temporal region of the gray short-tailed opossum Monodelphis domestica, the most commonly used experimental marsupial model, in order to more thoroughly understand the molecular basis of development of synapsid skulls unique to mammals. We found that M. domestica embryos and neonates display very restricted expressions of Msx2 and/or Runx2 in the dermal bone precursors in the temporal region, as two placental species do (the house mouse Mus musculus and the greater horseshoe bat Rhinolophus ferrumequinum). Spatially restricted expression of Msx2 and Runx2 in the embryonic temporal region may be a foundation for creating the "advanced" synapsid skull shared by all mammals where only three dermal bones configure the temporal region.

Keywords

amniote, bone, marsupial, Monodelphis domestica, temporal fenestrae

Introduction

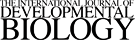

The skull of amniotes is categorized into three conditions based on skeletal arrangement in the temporal region (Rieppel, 1993; Tokita and Sato, 2022; Pough et al., 2023; Benton, 2024; Fig. 1). Anapsid skulls whose temporal region is completely roofed by bones are seen in turtles and basal reptiles (Sato et al., 2023). Since this skull condition was shared by a clade of anamniote tetrapods from which amniotes were derived (e.g. Diadectes and Orobates belonging to the order Diadectomorpha, a sister group of amniotes; Pough et al., 2023), anapsid skulls have been regarded as ancestral condition in amniotes. Synapsid skulls characterized by a single lower temporal arch, consisting of the jugal and quadratojugal or squamosal, that ventrally borders a temporal fenestration in the cheek region (lower temporal fenestra) are seen in the clade Synapsida, which includes all mammals (Sato et al., 2023). Diapsid skulls are characterized by two temporal arches: the upper temporal arch that consists of the postorbital and squamosal ventrally borders the upper temporal fenestra, and the lower temporal arch ventrally borders the lower temporal fenestra on each side of the skull (Sato et al., 2023). This skull condition is observed in extant “nonturtle” reptiles (lizards, snakes, tuatara, and crocodiles), birds, and their extinct relatives including dinosaurs.

Fig. 1. Three conditions of amniote skull and evolution of temporal skull morphology in Synapsida.

The skull of amniotes is classified into three types based on the number of temporal arches that ventrally border the temporal fenestrations shown as black ellipses (top). Each of the five temporal dermal bones are shaded in distinct colors (box at the bottom right). During evolution of the clade Synapsida, the number of temporal dermal bones has consistently reduced (bottom). The orbit and temporal fenestra have merged in the skulls of mammals (Mammalia), as shown in the illustrations of the skulls (middle). Note that the temporal region of the skulls of mammals is only covered by three temporal dermal bones (zygomatic, squamosal and parietal), making their skulls morphologically less disparate than those of reptiles. Abbreviations: ltf, lower temporal fenestra; n, naris; ob, orbit; tfo, temporal fossa; utf, upper temporal fenestra. Extinct taxa are labeled with dagger mark (†).

Although molecular mechanisms underlying the diversification of amniote temporal skull regions are poorly understood, our previous comparative molecular analysis of several representative amniote embryos revealed a possible correlation between osteogenic gene expression patterns in embryos and adult skull conditions, which may be a foundation of their cranial diversity (Sato et al., 2023). In stark contrast to reptilian and avian embryos that commonly showed broad expression of upstream osteogenic genes Msx2 and/or Runx2 in the temporal mesenchyme, the embryos of two eutherian (placental) mammal species we assessed displayed restricted expression of both upstream and downstream osteogenic genes in the dermal bone primordia within the temporal mesenchyme (Sato et al., 2023). The result implies that the reduction in the expression domain of Msx2 and Runx2 in the temporal mesenchyme of mammalian embryos contributed to the evolution of synapsid skulls whose temporal region is morphologically less disparate than that of reptiles (Brocklehurst et al., 2022; Fig. 1).

Living mammals consist of three major clades: monotremes (order Monotremata), marsupials (infraclass Marsupialia), and placentals (infraclass Placentalia) (Usui and Tokita, 2018; Feldhamer et al., 2020; Pough et al., 2023). Marsupials are characterized by retention of epipubic bones that project forward from the pelvis, the angular process of the dentary bending inward, distinctive arrangements of teeth, and shorter gestation period (Feldhamer et al., 2020; Pough et al., 2023). Marsupials show significantly less cranial disparity than placentals and developmental constraints likely played a role in this limitation of marsupial skull evolution (Bennett and Goswami, 2013). In addition, marsupial cranial development represents a more derived mode of mammalian development characterized by paedomorphosis (White et al., 2023). Furthermore, multiple lines of evidence suggest that changes in developmental timing (i.e., heterochrony) have played an important role in the divergence of marsupials and placentals. Marsupials have been shown to have earlier differentiation and migration of the cranial neural crest cells (Vaglia and Smith, 2003; Smith, 2006; Newton, 2022), which generate key portions of the skull, and is overall paedomorphic (White et al., 2023). However, irrespective of distinctive features in cranial development displayed by marsupials, molecular mechanisms of marsupial skull development are largely unknown.

Here, we focused on the gray short-tailed opossum Monodelphis domestica, the most commonly used experimental marsupial model (Keyte and Smith, 2009; Kiyonari et al., 2021). The data regarding cranial morphogenesis including chondrocranium development (Sánchez-Villagra and Forasiepi, 2017), dermatocranium development (Clark and Smith, 1993; Morris et al., 2024), and gene expression patterns during neural crest development (Wakamatsu et al., 2014) and odontogenesis (Moustakas et al., 2011; Wakamatsu et al., 2019) have been already available for this marsupial species. The aim of this study is to newly obtain the basic data regarding expression of osteogenic genes during marsupial skull development and compare them with those during placental skull development. We investigated expression patterns of four osteogenic genes, i.e., two upstream genes Msx2 and Runx2 and two downstream genes Sp7 and Sparc, in the temporal region of M. domestica embryos and neonates. Further, we compared the expression patterns of each osteogenic gene in M. domestica with those in two placental species: the house mouse Mus musculus and the greater horseshoe bat Rhinolophus ferrumequinum.

Results and Discussion

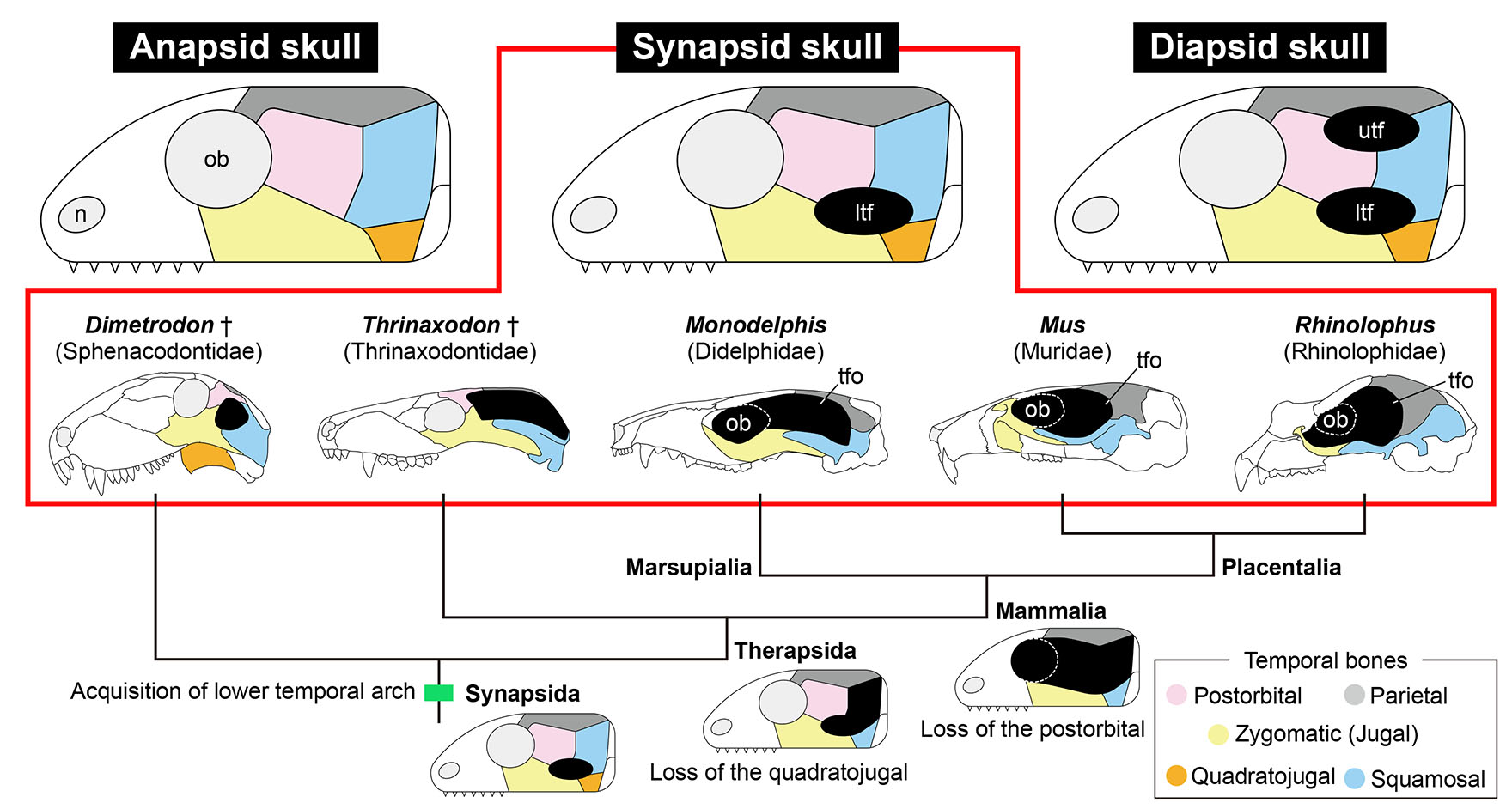

In order to assess the position, size, and timing of osteogenesis in the temporal region of embryos and neonates of the gray short-tailed opossum Monodelphis domestica, we employed a section in situ hybridization (see Materials and Methods for details). Four genes which are expressed across osteoblast differentiation were selected for this analysis: (1) Runx2, a preosteoblast marker; (2) Msx2, an upstream regulator of Runx2; (3) Sp7 (osterix), a downstream osteoblast marker of Runx2; and (4) Sparc (osteonectin), expressed in immature osteoblasts (Ferguson and Atit, 2019; Salhotra et al., 2020; Tokita and Sato, 2022).

In M. domestica embryos at embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5), which correspond to Stage (st.) 32 by McCrady (1938), the temporal dermal bones were not yet visible (Fig. 2 D,E). Regional expression of Msx2 was detected in the temporal mesenchyme dorsolateral to the trigeminal ganglion (Fig. 2F). At the more posterior otic capsule level of the same stage embryos, Msx2 was expressed in the temporal mesenchyme dorsolateral to the otic capsule (Fig. 2G). Restricted expression of Runx2 was detected in the mesenchyme dorsolateral as well as ventrolateral to the trigeminal ganglion and the mesenchyme dorsolateral to the otic capsule (Fig. 2 H,I). Expression of Sp7 and Sparc were not detected in the temporal mesenchyme at this embryonic stage (Fig. 2 J-L).

Fig. 2. Spatially restricted osteogenic gene expression in mammalian embryos prior to temporal dermal bone formation.

(A) Diagrams showing a lateral view of the head of a gray short-tailed opossum Monodelphis domestica embryo at embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5; st.32) (left) and frontal sections of the plane containing the trigeminal ganglion (tg) and otic capsule (ot) (right). (B,C) Lateral view of the head of embryos from M. domestica, the house mouse Mus musculus, and the greater horseshoe bat Rhinolophus ferrumequinum. The vertical dashed lines indicate the plane at which sections were prepared. (D) Hematoxylin, eosin, and alcian blue (HE) staining of the frontal section of the plane containing the right trigeminal ganglion (tg) of three mammalian species at the embryonic stages prior to cranial dermal bone formation. (E) HE staining of the plane containing the right otic capsule (ot), which is more posterior to the plane given in panel (D). (F-M) In situ hybridizations of Msx2, Runx2, Sp7 and Sparc at the sections adjacent to HE-stained sections given in the panels (D,E). At this ontogenetic stage, the temporal regions lateral to the trigeminal ganglion and the otic capsule are occupied by mesenchymal cells in all three mammalian species (D,E). Msx2 is regionally expressed in the temporal mesenchyme dorsolateral to the trigeminal ganglion and the otic capsule (F,G, arrowheads). Runx2 expression is restricted in the temporal mesenchyme dorsolateral as well as ventrolateral to the trigeminal ganglion, and the mesenchyme dorsolateral to the otic capsule (H,I, arrows). Expression of Sp7 and Sparc was not detected in the temporal mesenchyme of all three species at this ontogenetic stage (J-M). Scale bars, 200 µm.

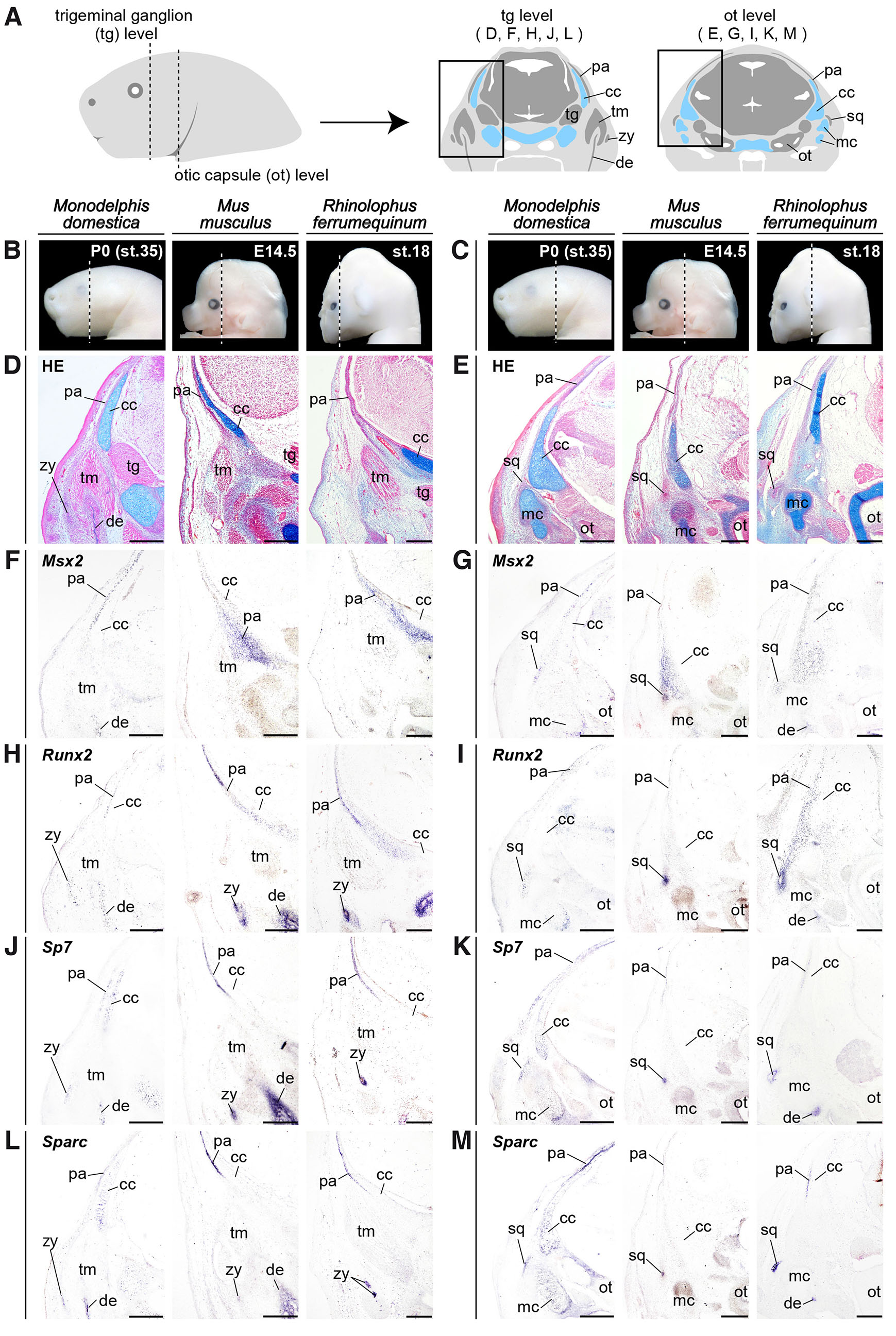

In M. domestica neonates at postnatal day 0 (P0), which correspond to Stage (st.) 35 by McCrady (1938), the precursors of three temporal dermal bones: the parietal, the zygomatic (jugal), and the squamosal appeared in the temporal region (Fig. 3 D,E). Msx2 was focally expressed in the parietal and squamosal precursors (Fig. 3 F,G). Restricted expression of Runx2 was detected in the parietal, zygomatic, and squamosal precursors (Fig. 3 H,I). Sp7 and Sparc were focally expressed in the parietal, zygomatic, and squamosal precursors (Fig. 3 J-L). At this neonatal stage, Sp7 and Sparc expressions were also detected in the alcian blue-positive chondrocytes within the endochondral bone precursors located in the whole body (Fig. 3 D,E, J-L; Supplementary Material).

Fig. 3. Spatially restricted osteogenic gene expression in opossum neonates and placental embryos during temporal dermal bone formation.

(A) Diagrams showing a lateral view of the head of a gray short-tailed opossum Monodelphis domestica neonate at postnatal day 0 (P0; st.35) (left) and frontal sections of the plane containing the trigeminal ganglion (tg) and otic capsule (ot) (right). (B,C) Lateral view pictures of the head of M. domestica neonate, the house mouse Mus musculus embryo, and the greater horseshoe bat Rhinolophus ferrumequinum embryo. The vertical dashed lines indicate the plane at which sections were prepared. (D) Hematoxylin, eosin, and alcian blue (HE) staining of the frontal section of the plane containing the right trigeminal ganglion (tg) of three mammalian species at the embryonic and neonatal stages during cranial dermal bone formation. (E) HE staining of the plane containing the right otic capsule (ot), which is more posterior to the plane given in the panel (D). (F-M) In situ hybridizations of Msx2, Runx2, Sp7 and Sparc at the sections adjacent to the HE stained sections given in the panels (D,E). At this ontogenetic stage, the parietal, zygomatic (jugal), and squamosal precursors are visible in all three mammalian species (D,E). Msx2 is focally expressed in the parietal and squamosal precursors (F,G). Runx2 expression is restricted in the parietal, zygomatic, and squamosal precursors (H,I). Focal expressions of Sp7 and Sparc are detected in the parietal, zygomatic and squamosal precursors of three mammalian species (J-M). Unique expression of both Sp7 and Sparc was detected in alcian blue-positive chondrocytes within the endochondral bone precursors of M. domestica neonates (J-M). Abbreviations: cc, chondrocranium; de, dentary; mc, Meckel's cartilage; ot, otic capsule; pa, parietal; sq, squamosal; tg, trigeminal ganglion; tm, temporal muscle; zy, zygomatic. Scale bars, 200 µm.

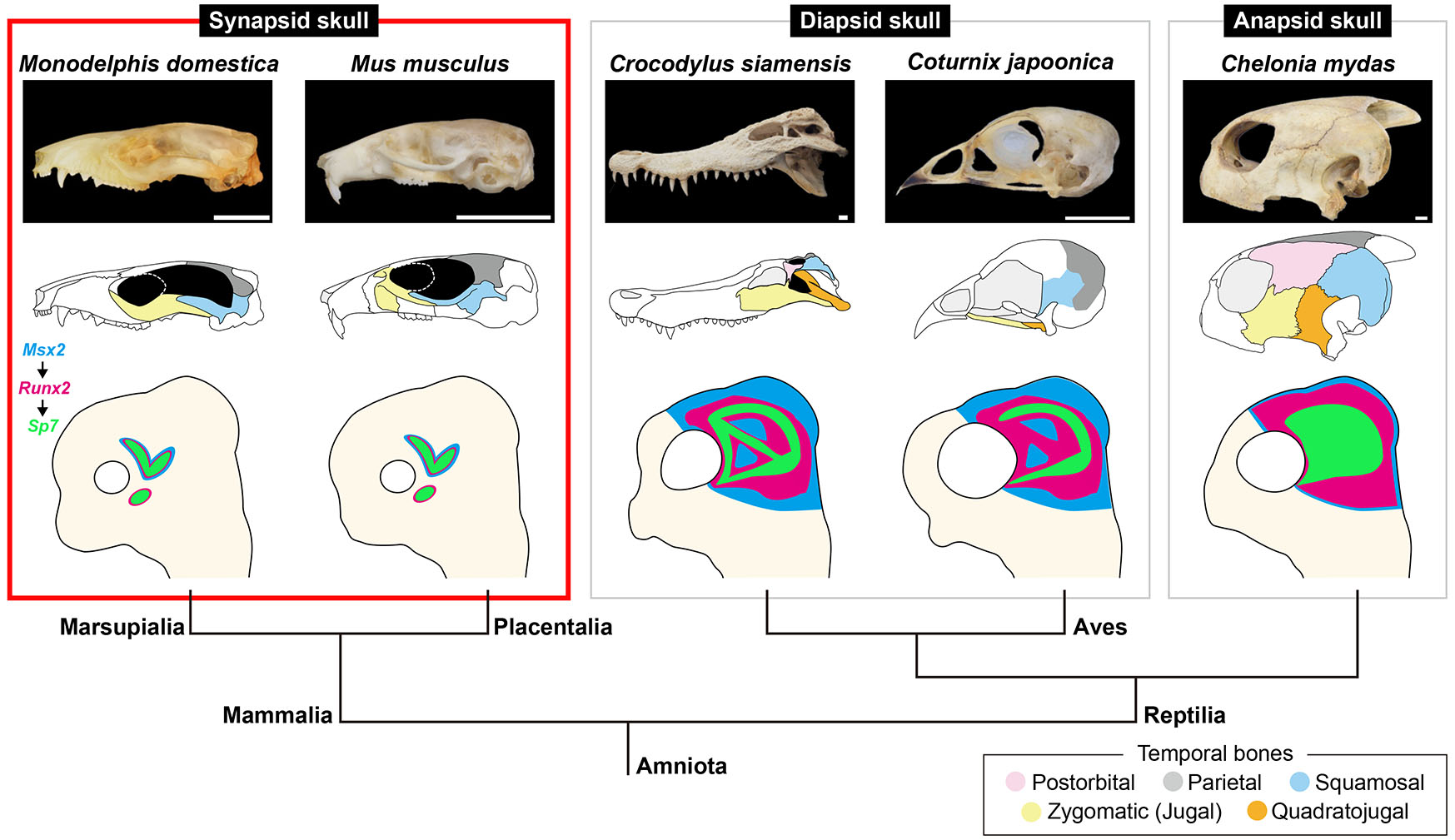

A comparison of the expression patterns of Msx2, Runx2, Sp7, and Sparc in the temporal region between the marsupial (M. domestica) embryos/neonates and the placental (the house mouse Mus musculus and the greater horseshoe bat Rhinolophus ferrumequinum) embryos, as well as between mammals and non-mammalian amniotes (the Siamese crocodile Crocodylus siamensis and the Japanese quail Coturnix japonica with diapsid skulls, and the green sea turtle Chelonia mydas with an anapsid skull) revealed a potential developmental basis of synapsid skulls unique to mammals. Embryos of all three mammalian species we assessed displayed very restricted expressions of Msx2 and/or Runx2 in the dermal bone precursors in the temporal region (Figs. 2, 3, 4). In contrast, in reptilian and avian embryos we assessed, both genes were broadly expressed in the temporal mesenchyme (Fig. 4; Sato et al., 2023). For more downstream osteogenic genes Sp7 and Sparc, focal expressions in the temporal dermal bone precursors were detected in both mammalian and reptilian-avian lineages (Figs. 3, 4; Sato et al., 2023).

Fig. 4. Potential developmental basis of the mammalian temporal skull region.

(Top row) Lateral view pictures of the skulls of the gray short-tailed opossum Monodelphis domestica, the house mouse Mus musculus, the Siamese crocodile Crocodylus siamensis, the Japanese quail Coturnix japonica, the green sea turtle Chelonia mydas. (Middle row) Illustrations of the skulls where the temporal dermal bones are shaded in distinct colors (box at the bottom right). (Bottom row) Illustrations of the neonatal or embryonic head accompanied with a phylogenetic tree. Expression domains of Msx2, Runx2 and Sp7 in the temporal region are shown in blue, magenta, and green, respectively. Mammalian species analyzed in this study showed regional expression of Msx2 and Runx2 in the parietal and squamosal precursors. Runx2 was additionally expressed in the zygomatic (jugal) precursor. In contrast, in the reptilian and avian species examined previously, Msx2 and Runx2 were broadly expressed in the temporal mesenchyme (Sato et al., 2023). Sp7 and Sparc were focally expressed in the temporal dermal bone precursors in both mammalian and reptilian-avian lineages. During the cranial evolution of synapsids, the number of the temporal dermal bone elements has consistently decreased. As a result, the temporal skull region of mammals, which was derived from synapsids, is morphologically less disparate than that of reptiles and birds. This may be attributed to the reduction of the domain where Msx2- and Runx2-positive temporal mesenchyme with osteogenic potential is distributed, throughout synapsid evolution. Scale bars, 10 mm.

The number of the skull bone elements has consistently decreased during synapsid evolution (Sidor, 2001; Kean et al., 2024). First, at the divergence of the clade Therapsida such as Thrinaxodon (Fig. 1), the quadratojugal disappeared. Subsequently, the postorbital was lost in the clade Mammalia to which all living mammals including opossums, mice, and bats are belonging (Fig. 1). As a result, the temporal skull region of mammals consists of only three dermal bones: the zygomatic (jugal), parietal, and squamosal and is morphologically less disparate than that of reptiles whose temporal region is typically covered with four or all five dermal bones (Figs. 1, 4; Sato et al., 2023). Spatially restricted expressions of Msx2 and Runx2 in the temporal region, which we observed in both marsupial and placental species, may be the developmental basis of the "advanced" synapsid skull shared by all mammals where only three dermal bones configure the temporal region, and the temporal fossa is present (Figs. 1, 4). We speculate that expression of these upstream osteogenic genes in the head of embryos of early synapsids (e.g. Sphenacodontidae represented by Dimetrodon) that possessed all five temporal dermal bones (Fig. 1) was regulated in a manner similar to that in reptiles. Then, the expression of both Msx2 and Runx2 was lost in the mesenchyme which later differentiates into the quadratojugal at the divergence of therapsids (Fig. 1). This could be due to loss of the enhancer that activates Msx2 and Runx2 expression in the quadratojugal precursor of therapsid embryos. Finally, expression of both genes was repressed in the embryonic mesenchyme, giving rise to the postorbital in the lineage of mammals (Fig. 1); this molecular event may result in the creation of the temporal fossa, through the merger of the lower temporal fenestra and the orbit.

Currently, seven extant clades of Marsupialia are recognized: Paucituberculata, Didelphimorphia, and Microbiotheria in the New World and Diprotodontia, Notoryctemorphia, Peramelemorphia, and Dasyuromorphia in Australia and New Guinea (Eldridge et al., 2019; Pough et al., 2023). M. domestica examined in the present study is a member of basal American marsupial (superorder Ameridelphia; order Didelphimorphia) diverged from Australian marsupials about 80 million years ago (Newton, 2022). To evaluate uniformity and diversity in the developmental basis of the synapsid skulls of mammals more precisely, investigation of osteogenic gene expression patterns in the embryonic and neonatal temporal region of Australian marsupials (such as the fat-tailed dunnart Sminthopsis crassicaudata, which is becoming a new marsupial model species for developmental biology (Suárez et al., 2017; Cook et al., 2021; Newton et al., 2024)), should be done. Osteogenic gene expression patterns in the embryos of monotremes (a platypus and echidnas), whose skull morphogenesis has been partially described (Gaupp, 1908; Watson, 1916; de Beer and Fell, 1936; Kuhn, 1971; reviewed by Clark and Smith, 1993), will be desired as well to fully understand the molecular basis of synapsid skulls unique to mammals.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection and staging of embryos and neonates

Embryos and neonates of the gray short-tailed opossum Monodelphis domestica were sampled in the Laboratory for Animal Resources and Genetic Engineering, RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research, Japan, and staged on the basis of McCrady (1938). Pregnant females of the greater horseshoe bat Rhinolophus ferrumequinum were collected in Niigata prefecture, Japan in 2018 and 2022, and the embryos were staged on the basis of Usui and Tokita (2019). Embryos of the house mouse Mus musculus were sampled in Prof. Iseki’s laboratory at Institute of Science Tokyo, Japan and staged on the basis of Kaufman (1992). To determine which stages are most comparable in terms of skull development among three mammalian species, the previous studies were referred (Kaufman, 1992; Clark and Smith, 1993; Nojiri et al., 2018; Morris et al., 2024). After the assessment, M. domestica embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5; st.32) and postnatal day 0 (P0; st.35); M. musculus E12.5 and E14.5; R. ferrumequinum st. 15.5 and 18 were analyzed in our interspecific comparisons. All animal experiments were approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the Faculty of Science, Toho University (permits 15-51-301, 16-52-301, 17-53- 301, 18-54-301, 19-55-301, 20-51-449, and 21-52-449).

Molecular cloning and phylogenetic analysis

Total RNA was extracted from embryos using NucleoSpin RNA (Macherey-Nagel), and cDNA was synthesized with the PrimeScript II first strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (TaKaRa). The polymerase chain reaction was performed with GoTaq® Master Mixes (Promega), PrimeStar GXL and ExTaq DNA polymerases (TaKaRa) to amplify DNA fragments. Amplified fragments were isolated using the pGEM®-T Easy Vector Systems (Promega). To identify the orthologous genes of the isolated fragments, comparable sequence data were surveyed using a Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) of National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Sequence data of isolated genes were deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) database, and the accession numbers of each gene and the primers used in PCR are listed in Table 1.

Table 1

Primers for cloning the genes analyzed in the current study and accession numbers for the sequence of each gene cloned

| Gene | Forward | Reverse | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|

| M. domestica Msx2 | AAGGCACATCCAGGACCATG CAAATCGGAAGCCCAGGACT |

TCTCAGAGGCAGCCAGGTAT CCCAGCCTGGAAATCTGCTT |

LC900795 |

| M. domestica Runx2 | CATTCCACCACCCCTCTGTC TGGTTTTGAAGGGGAGTGGG |

CTCCCTACTCACCCCCATGA |

LC900796 |

| M. domestica Sp7 | GTGAACTCTCAGCCCCCAAA CTCCATTTGCAGGCACCAAC |

TCTGGGGAAATTGGTGAGGC |

LC900797 |

| M. domestica Sparc | ATGCGTGACTGGCTGAAGAA GAAGCGTCTAGAAGCCGGAG |

GGTCCTAGCAAGCAGAAGCA GAGGAAAGGACCTGGGTGTC |

LC900798 |

Histological and gene expression analyses

Embryos and neonates were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/phosphate-buffered saline (PFA/PBS) for 3 days, then dehydrated using a methanol series, embedded in paraffin, and sliced at a thickness of 10μm. For histological analysis, sliced sections were deparaffinized and stained with hematoxylin, eosin, and alcian blue solutions with standard protocols. For section in situ hybridization, sliced sections were deparaffinized and hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes synthesized by following the manufacturer’s protocol (https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/deepweb/assets/sigmaaldrich/marketing/global/documents/287/736/dig-application-manual-for-nonradioactive-in-situ-hybridisation-iris.pdf, Roche Diagnostics GmbH). Anti-digoxigenin-alkaline phosphatase (AP) antibody, nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT), and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-phosphate (BCIP) (11093274910, 11383213001, and 11383221001, Roche) were used to detect signals. Stained sections were photographed with a camera (DS-Fi3, Nikon) mounted on a microscope (Eclipse Ni, Nikon). More than three embryos/neonates at each ontogenetic stage were examined for each mammalian species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We appreciate Dr. Sachiko Iseki for supplying mouse embryos, Dr. Kaoru Usui for bat embryos, and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments. This research was funded by MEXT/JSPS KAKENHI grant number JP21KK0133 to MT.

References

Bennett C. V., Goswami A. (2013). Statistical support for the hypothesis of developmental constraint in marsupial skull evolution. BMC Biology 11: 52.

Benton M. J., (2024). Vertebrate Palaeontology. Wiley.

Brocklehurst N., Ford D. P., Benson R. B. J. (2022). Early Origins of Divergent Patterns of Morphological Evolution on the Mammal and Reptile Stem-Lineages. Systematic Biology 71: 1195-1209.

Clark C. T., Smith K. K. (1993). Cranial osteogenesis in Monodelphis domestica (Didelphidae) and Macropus eugenii (Macropodidae). Journal of Morphology 215: 119-149.

Cook L. E., Newton A. H., Hipsley C. A., Pask A. J. (2021). Postnatal development in a marsupial model, the fat-tailed dunnart (Sminthopsis crassicaudata; Dasyuromorphia: Dasyuridae). Communications Biology 4: 1028.

de Beer G. R., Fell W. A. (1936). The Development of the Monotremata.–Part III. The Development of the Skull of Ornithorhynchus. The Transactions of the Zoological Society of London 23: 1-42.

Eldridge M. D. B., Beck R. M. D., Croft D. A., Travouillon K. J., Fox B. J. (2019). An emerging consensus in the evolution, phylogeny, and systematics of marsupials and their fossil relatives (Metatheria). Journal of Mammalogy 100: 802-837.

Feldhamer G. A., Merritt J. F., Krajewski C., Rachlow J. L., Stewart K. M., (2020). Mammalogy: Adaptation, Diversity, Ecology. Johns Hopkins University.

Ferguson J. W., Atit R. P. (2019). A tale of two cities: The genetic mechanisms governing calvarial bone development. Genesis 57: e23248.

Gaupp E., (1908). Zur Entwicklungsgeschichte und Vergleichenden Morphologie des Schädels von Echidna aculeuta var. typica. Semon, Zoologische Forschungsreisen in Australien und dem Malayischen Archipel. Denkschriften der Medizinisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Gesellschaft zu Jena 6: 539-788.

Kaufman M. K., (1992). The Atlas of Mouse Development. Academic Press.

Kean K. J., Danto M., Pérez-Ben C., Fröbisch N. B. (2024). Evolution of the tetrapod skull: a systematic review of bone loss. Fossil Record 27: 445-471.

Keyte A. L., Smith K. K., (2009). Opossum (Monodelphis domestica): A marsupial developmental model. In Emerging Model Organisms: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

Kiyonari H., Kaneko M., Abe T., Shiraishi A., Yoshimi R., Inoue K., Furuta Y. (2021). Targeted gene disruption in a marsupial, Monodelphis domestica, by CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Current Biology 31: 3956-3963.e4.

Kuhn H.-J., (1971). Die Entwicklung und Morphologie des Schädels von Tachyglossus aculeatus. Abh. Senckenberg Naturforsch. Ges. 528: l-192.

McCrady E., (1938). The Embryology of the Opossum. Wistar Institute of Anatomy.

Morris Z. S., Colbert M. W., Rowe T. B. (2024). Variation and Variability in Skeletal Ossification of the Gray Short-tailed Opossum, Monodelphis domestica. Integrative Organismal Biology 6: obae024.

Moustakas J. E., Smith K. K., Hlusko L. J. (2011). Evolution and development of the mammalian dentition: Insights from the marsupial Monodelphis domestica. Developmental Dynamics 240: 232-239.

Newton A. H. (2022). Marsupials and Multi-Omics: Establishing New Comparative Models of Neural Crest Patterning and Craniofacial Development. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 10: 941168.

Newton A. H., Hutchison J. C., Farley E. R., Scicluna E. L., Youngson N. A., Liu J., Menzies B. R., Hildebrandt T. B., Lawrence B. M., Sutherland A. H. W., Potter D. L., Tarulli G. A., Selwood L., Frankenberg S., Ord S., Pask A. J. (2024). Embryology of the fat‐tailed dunnart ( Sminthopsis crassicaudata ): A marsupial model for comparative mammalian developmental and evolutionary biology. Developmental Dynamics 254: 142-157.

Nojiri T., Werneburg I., Son N. T., Tu V. T., Sasaki T., Maekawa Y., Koyabu D. (2018). Prenatal cranial bone development of Thomas's horseshoe bat ( Rhinolophus thomasi ): with special reference to petrosal morphology. Journal of Morphology 279: 809-827.

Pough H., Bemis W. E., McGuire B., Janis C. M., (2023). Vertebrate Life. Sinauer Associates.

Rieppel O., (1993). Patterns of diversity in the reptilian skull. In The Skull. (Ed. Hall B. K., Hanken J., ) University of Chicago Press.

Salhotra A., Shah H. N., Levi B., Longaker M. T. (2020). Mechanisms of bone development and repair. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 21: 696-711.

Sánchez-Villagra M. R., Forasiepi A. M. (2017). On the development of the chondrocranium and the histological anatomy of the head in perinatal stages of marsupial mammals. Zoological Letters 3: 1.

Sato H., Adachi N., Kondo S., Kitayama C., Tokita M. (2023). Turtle skull development unveils a molecular basis for amniote cranial diversity. Science Advances 9: eadi6765.

Sidor C. A. (2001). SIMPLIFICATION AS A TREND IN SYNAPSID CRANIAL EVOLUTION. Evolution 55: 1419-1442.

Smith K. K. (2006). Craniofacial development in marsupial mammals: Developmental origins of evolutionary change. Developmental Dynamics 235: 1181-1193.

Suárez R., Paolino A., Kozulin P., Fenlon L. R., Morcom L. R., Englebright R., O’Hara P. J., Murray P. J., Richards L. J. (2017). Development of body, head and brain features in the Australian fat-tailed dunnart (Sminthopsis crassicaudata; Marsupialia: Dasyuridae); A postnatal model of forebrain formation. PLOS ONE 12: e0184450.

Tokita M., Sato H. (2022). Creating morphological diversity in reptilian temporal skull region: A review of potential developmental mechanisms. Evolution & Development 25: 15-31.

Usui K., Tokita M. (2018). Creating diversity in mammalian facial morphology: a review of potential developmental mechanisms. EvoDevo 9: 15.

Usui K., Tokita M. (2019). Normal embryonic development of the greater horseshoe bat Rhinolophus ferrumequinum , with special reference to nose leaf formation. Journal of Morphology 280: 1309-1322.

Vaglia J. L., Smith K. K. (2003). Early differentiation and migration of cranial neural crest in the opossum, Monodelphis domestica. Evolution & Development 5: 121-135.

Wakamatsu Y., Nomura T., Osumi N., Suzuki K. (2014). Comparative gene expression analyses reveal heterochrony for Sox9 expression in the cranial neural crest during marsupial development. Evolution & Development 16: 197-206.

Wakamatsu Y., Egawa S., Terashita Y., Kawasaki H., Tamura K., Suzuki K. (2019). Homeobox code model of heterodont tooth in mammals revised. Scientific Reports 9: 12865.

Watson D. M. S., (1916). The monotreme skull: A contribution to mammalian morphogenesis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 207: 311-374.

White H. E., Tucker A. S., Fernandez V., Portela Miguez R., Hautier L., Herrel A., Urban D. J., Sears K. E., Goswami A. (2023). Pedomorphosis in the ancestry of marsupial mammals. Current Biology 33: 2136-2150.e4.