Int. J. Dev. Biol. 69: 143 - 150 (2025)

Spatiotemporal expression of carnitine palmitoyltransferase I genes during zebrafish development and heart regeneration

Open Access | Developmental Expression Pattern | Published: 19 November 2025

Abstract

Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1) is a key regulatory enzyme in fatty acid metabolism, responsible for the translocation of long-chain fatty acids into the mitochondria for β-oxidation in diverse biological contexts. Recent studies implicated the critical role of cpt1 genes during zebrafish development and heart regeneration; however, a comprehensive characterization of their spatiotemporal expression dynamics remains lacking. Here, we systematically analyzed the expression profiles of four cpt1 paralogs (cpt1aa, cpt1ab, cpt1b, and cpt1a2b) during zebrafish embryogenesis and the expression of cpt1ab and cpt1b during zebrafish heart regeneration. Our results reveal that these paralogs exhibit distinct spatiotemporal expression patterns during zygotic development. While cpt1aa and cpt1ab share high sequence conservation (77%), their expression patterns diverge substantially. Conversely, cpt1ab and cpt1b display convergent cardiac and somitic expression despite lower sequence similarity (53%). Following ventricular ablation, cpt1b expression transiently ceased then recovered during regeneration, whereas cpt1ab remained unchanged. These findings shed light on the evolutionary conservation and functional divergence of cpt1 paralogs, which establish a critical foundation for elucidating paralog-specific roles in fatty acid metabolism during vertebrate development and regeneration.

Keywords

Carnitine palmitoyltransferase, cpt1, development, heart regeneration, expression, zebrafish

Introduction

Fatty acid metabolism sustains energy homeostasis, membrane biogenesis and signal transduction. Carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (Cpt1), a key rate-limiting enzyme in fatty acid beta-oxidation, facilitates the transport of long-chain fatty acids into mitochondria for energy metabolism (Schlaepfer and Joshi, 2020). The mammalian CPT1 gene family consists of three paralogs: Cpt1a, Cpt1b, and Cpt1c, each exhibiting distinct tissue distributions, enzymatic activities and regulatory mechanisms (Wang et al., 2021). Early studies have shown that human and/or mouse CPT1A is predominantly expressed in the liver, CPT1B in muscle tissues, and CPT1C in the brain (Britton et al., 1995; Yamazaki, 2004; Price et al., 2002; Wolfgang et al., 2006). The expression of Cpt1 genes is highly regulated under various physiological and pathological conditions. For instance, Cpt1b expression is transiently increased after birth (Bartelds et al., 2004; Brown et al., 1995; Lavrentyev et al., 2004) in rats and lambs, and can be induced by exercise or high fructose diet (Shen et al., 2015; Melendez-Salcido et al., 2025) in rats and mice, suggesting that Cpt1 plays a crucial role in the regulatory response to metabolic stress. As a pivotal regulatory enzyme in fatty acid metabolism, Cpt1 is not only closely associated with metabolic diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and fatty liver, but also widely involved in the development, growth and heart regeneration (Cao et al., 2019; Li et al., 2023; Ji et al., 2008). Nevertheless, the studies of the expression and roles of Cpt1 genes in early development remain relatively scarce.

Zebrafish, as an important model organism, has a highly conserved early developmental process with mammals, providing an ideal model for studying gene function and developmental regulation. Previous phylogenetic analyses identified four cpt1 genes from zebrafish genome—cpt1aa, cpt1ab, cpt1b, and cpt1a2b (Morash et al., 2010; Lopes-Marques et al., 2015). Among these, cpt1aa and cpt1ab, generated after the teleost-specific genome duplication (TGD), are orthologs of mammalian Cpt1a, and cpt1b is the ortholog of mammalian Cpt1b, while the orthologous relationship of cpt1a2b gene remains controversial (Morash et al., 2010; Lopes-Marques et al., 2015). Conservation analysis demonstrates higher protein sequence similarity between cpt1a2b and human CPT1A, whereas synteny analysis supports potential cpt1a2b orthology with human CPT1C (Lopes-Marques et al., 2015).

Recently, zebrafish have been adopted to study the role of cpt1 genes in energy homeostasis, early development and heart regeneration. For instance, Li et al., found that knocking out cpt1b in zebrafish reduced fatty acid oxidation and induced energy homeostasis remodeling in the liver and muscle (Li et al., 2020); Zecchin et al., and Ulhaq et al., reported that cpt1a knockdown impaired cilia growth, photoreceptor cell and lymphatics development (Ulhaq et al., 2023; Zecchin et al., 2018); we and Zhao et al., found that fatty acid oxidation and cpt1b are essential for cardiomyocyte proliferation and ventricle regeneration (Zhao et al., 2024; Cheng et al., 2024). These studies highlight the rising significance of characterizing the role and mechanism of cpt1 genes in zebrafish embryos. Despite this, the spatial-temporal expression of zebrafish cpt1 genes has not yet been well studied.

In this study, we systematically profile the spatiotemporal expression of zebrafish cpt1 genes throughout early development and during heart regeneration using in situ hybridization technique, which will provide important experimental evidence to understand the role of cpt1 genes and fatty acid metabolism during embryonic development and heart regeneration.

Results

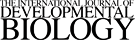

Phylogenetic analysis of CPT1 gene family in evolution

To comprehensively characterize the CPT1 gene family in zebrafish, we systematically queried the Zebrafish Information Network (ZFIN) database, and identified five putative paralogs: cpt1aa, cpt1ab, cpt1b, cpt1a2a, and cpt1a2b. The cpt1a2a locus was excluded from subsequent studies due to its incomplete sequence (<500 nt) lacking discernible protein domains. For evolutionary conservation assessment, we retrieved CPT1 protein sequences from three teleost species—zebrafish (D. rerio), medaka (O. latipes) and Mexican tetra (A. mexicanus)—as well as five additional species representing major phylogenetic lineages: worm (C. elegans), fruitfly (D. melanogaster), Xenopus (X. tropicalis), mouse (M. musculus), and human (H. sapiens).

Consistent with previous studies (Morash et al., 2010; Lopes-Marques et al., 2015), teleost cpt1aa and cpt1ab represent co-orthologs of mammalian CPT1A originating from TGD, although only cpt1ab has been identified in the medaka genome (Fig. 1). Pairwise analysis reveals that zebrafish Cpt1aa and Cpt1ab share 71% and 72% amino acid identity with human CPT1A, respectively. Similarly, teleost cpt1b maintains direct orthology with mammalian CPT1B, with 65% amino acid identity between zebrafish Cpt1b and human CPT1B. The paralog cpt1a2b (formerly designated cpt1cb) exhibits greater evolutionary similarity with CPT1A than CPT1C, and zebrafish Cpt1a2b shares 66% identity with human CPT1A versus 53% with CPT1C. This phylogenetic positioning suggests functional divergence following genome duplication events.

Fig. 1. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of the carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1) gene family.

Evolutionary relationships of 22 CPT1 protein sequences across nine species. See Supplementary Data 1 for sequence accessions. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using ClustalX 2.1 and the resulting phylogeny was visualized and annotated using Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL v7).

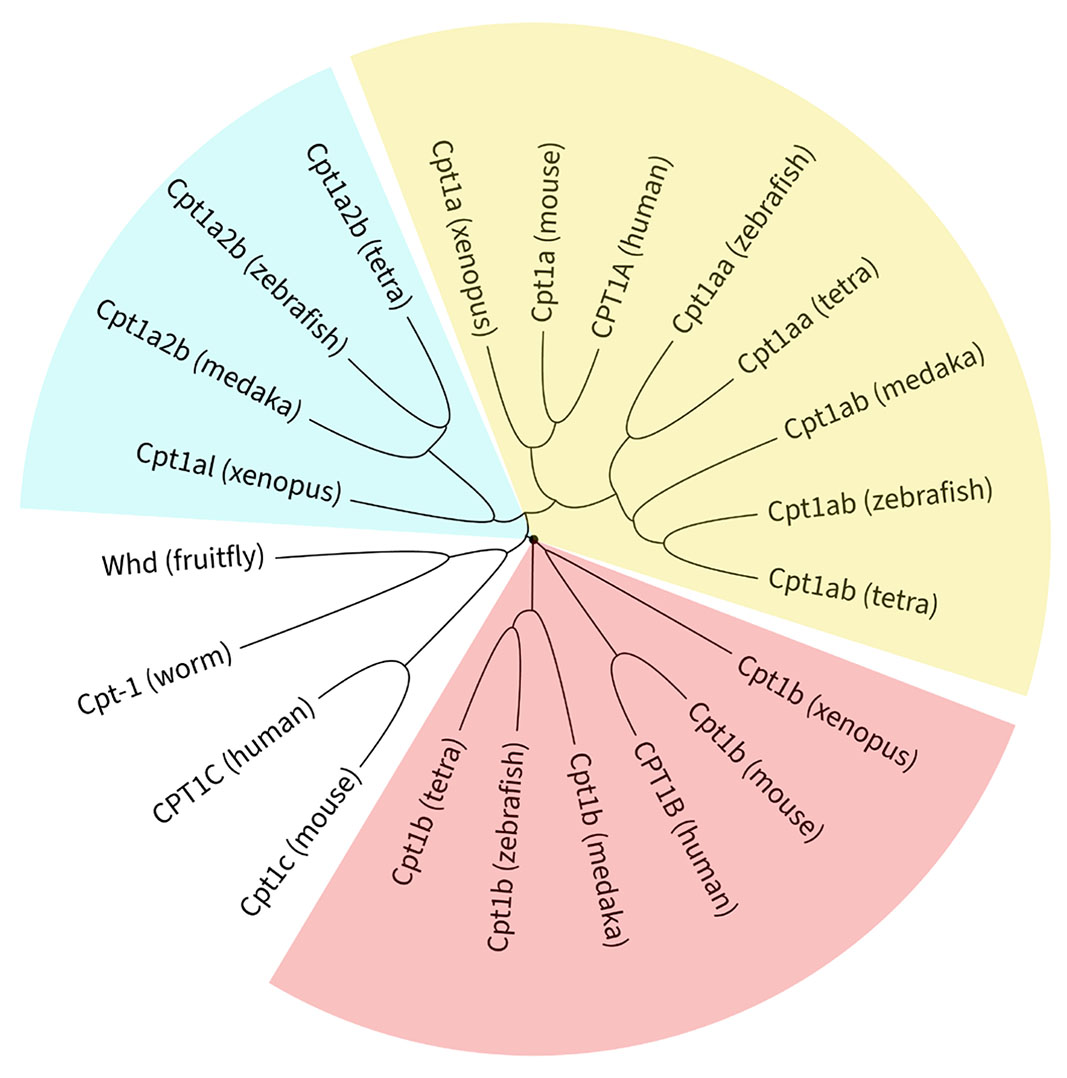

Spatiotemporal expression pattern of cpt1aa in zebrafish embryos

To systematically investigate the expression profile of cpt1aa gene during zebrafish embryonic development, whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) was performed using a cpt1aa-specific riboprobe across multiple critical developmental stages. As illustrated in Fig. 2, ubiquitous distribution of cpt1aa transcripts persists from 1-cell stage through bud stage (Fig. 2 A-D), indicating that cpt1aa is maternally expressed and maintains comparable expression beyond zygotic genome activation (ZGA). This pan-embryonic pattern undergoes progressive spatial restriction post-bud stage, with ctp1aa transcripts becoming enriched in the developing nervous system by 24 hours post-fertilization (hpf; Fig. 2E). By 2 days post-fertilization (dpf), cpt1aa exhibits differential neural compartmentalization, with strong signals persist in the brain, whereas spinal cord expression becomes undetectable (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2. Spatiotemporal expression of cpt1aa in zebrafish embryos.

Expression of cpt1aa in (A) 1-cell stage embryos, (B) 512-cell embryos, (C) shield stage embryos, (D) bud stage embryos, (E) 24 hpf embryos, (F) 2 dpf embryos, (G) 3 dpf embryos, (H) 4 dpf embryos, (I) 5 dpf embryos. The red triangles denote the livers. dpf, days post fertilization; hpf, hours post fertilization; scale bars: 200 µm.

At 3 dpf, concurrent with sustained cpt1aa expression in the developing brain, cpt1aa transcripts are robustly detected in the nascent hepatic bud (Fig. 2G), indicating early involvement of Cpt1aa-mediated β-oxidation during hepatic specification and metabolic maturation. Subsequent developmental progression reveals a complete neural-to-hepatic transition of cpt1aa expression starting from 4 to 5 dpf: brain signals become undetectable, whereas robust expression is maintained in the developing liver (Fig. 2 H-I). This spatiotemporal trajectory indicates that zebrafish cpt1aa, akin to mammalian Cpt1a, is predominantly expressed in the liver, although its widespread expression prior to liver morphogenesis suggests potential multifunctional roles beyond hepatic metabolism during early embryogenesis.

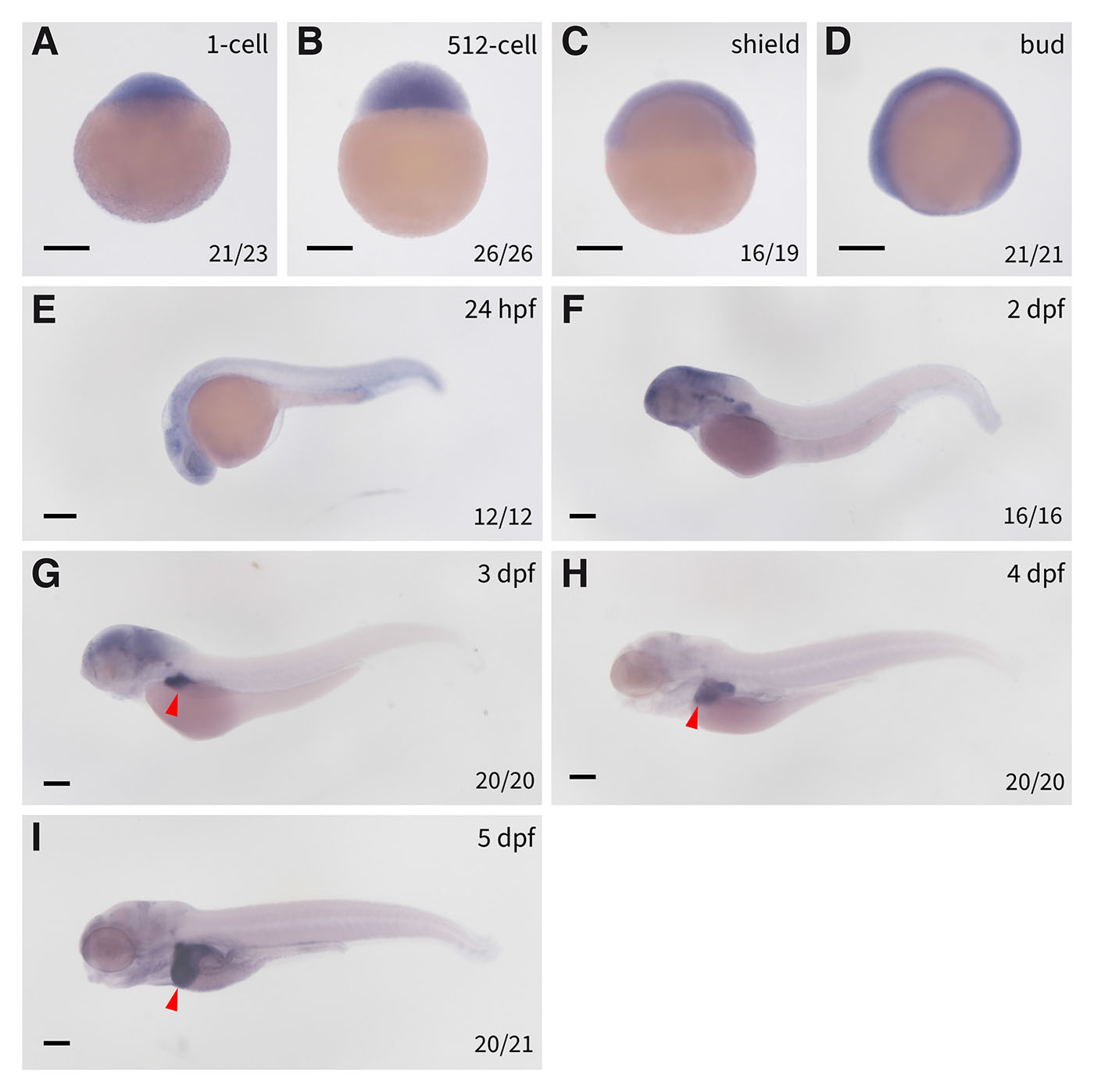

Divergent expression of cpt1ab following teleost genome duplication

Although cpt1ab shares ancestral orthology with cpt1aa, WISH analysis reveals distinct expression patterns that underscore their functional divergence. While maternal cpt1ab transcripts persist from 1-cell to 512-cell stages (Fig. 3 A-B), its expression vanishes from shield to bud stages (Fig. 3 C-D), suggesting complete degradation of maternal transcripts during gastrulation, which is contrast to the sustained post-ZGA expression observed for cpt1aa.

Fig. 3. Spatiotemporal expression of cpt1ab in zebrafish embryos.

Expression of cpt1ab in (A) 1-cell stage embryos, (B) 512-cell embryos, (C) shield stage embryos, (D) bud stage embryos, (E) 24 hpf embryos, (F) 2 dpf embryos (the inset is a ventral view of the embryo showing the expression of cpt1ab in the heart), (G) 3 dpf embryos, (H) 4 dpf embryos, (I) 5 dpf embryos. The red triangles denote the hearts, and the yellow triangles denote the liver and intestine. Scale bars: 200 µm.

De novo zygotic cpt1ab expression remain undetectable until 24 hpf, when transcripts are simultaneously detected in cardiac primordium and somitic musculature through 2 dpf (Fig. 3 E-F). Extensive tissue-specific modulation occurs from 3 dpf onward: cardiac expression persists robustly from 24 hpf to 5 dpf (Fig. 3 F-I), whereas somitic signals diminish significantly by 4 dpf (Fig. 3H). Concurrently, endodermal activation commences at 3 dpf in liver and intestinal precursors (Fig. 3G), which is significantly elevated at 4 and 5 dpf (Fig. 3 H-I), with pharyngeal arch expression emerging at 5 dpf (Fig. 3I). This biphasic expression kinetics—marked by early cardiac-somitic predominance followed by endodermal expansion—contrasts sharply with cpt1aa's hepatic commitment. Such divergence illustrates functional specialization following TGD, potentially facilitating metabolic adaptation in rapidly contracting tissues during early development, while supporting endodermal organ maturation in later stages.

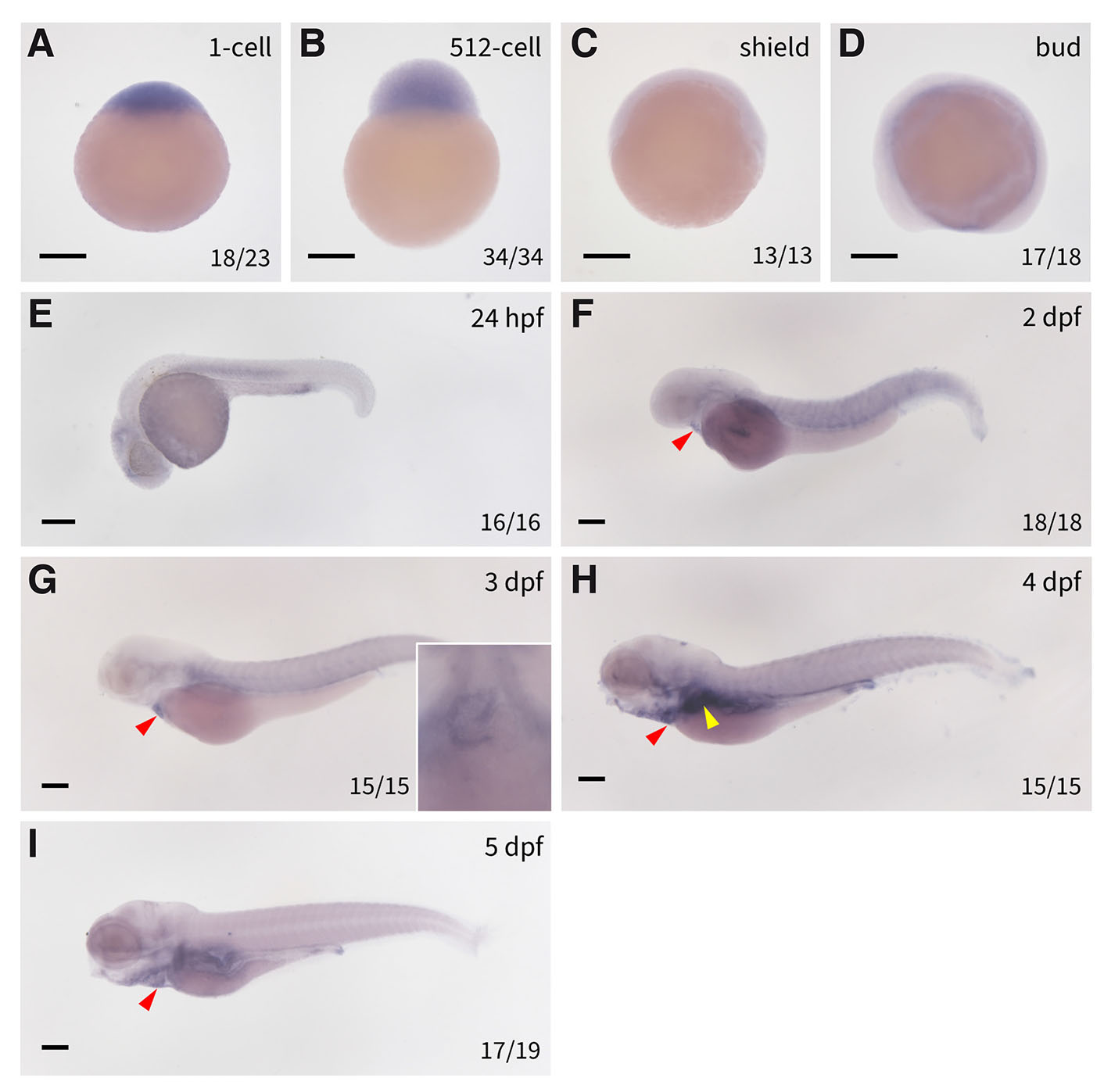

Conserved muscular expression of cpt1b in zebrafish embryos

Similar with cpt1ab, zebrafish cpt1b exhibits maternally deposited transcripts at 1-cell and 512-cell stages (Fig. 4 A-B), followed by post-ZGA degradation, as evidenced by diminished expression from shield to bud stages (Fig. 4 C-D). Zygotic ctp1b expression initiates at 24 hpf with transcripts detectable in developing myotomes (Fig. 4E). Cardiac expression emerges at 2 dpf with ventricular predominance by 3 dpf (Fig. 4 F-I), which is consistent with chamber-specific metabolic demands of the heart. Notably, strong cpt1b transcripts are transiently expressed in endodermal tissues, including the intestine and pharyngeal pouches (Fig. 4H), suggesting a transient adaption for enteric lipid metabolism during early development. The cardiac and muscular expression of cpt1b is consistent with previous studies showing that CPT1B is mainly expressed in muscular tissues and plays a predominant role in high-energy-demand tissues.

Fig. 4. Spatiotemporal expression of cpt1b in zebrafish embryos.

Expression of cpt1b in (A) 1-cell stage embryos, (B) 512-cell embryos, (C) shield stage embryos, (D) bud stage embryos, (E) 24 hpf embryos, (F) 2 dpf embryos, (G) 3 dpf embryos (the inset is a ventral view of the embryo showing the expression of cpt1b in the heart), (H) 4 dpf embryos and (I) 5 dpf embryos. The red triangles denote the hearts, and the yellow triangle denotes the developing liver. Scale bars: 200 µm.

Spatially restricted expression of cpt1a2b in zebrafish embryos

Similar to other cpt1 paralogs, cpt1a2b exhibits conserved maternal transcript deposition (Fig. 5 A-B), yet exhibits distinct post-ZGA dynamics. While cpt1aa maintains a relatively stable expression level post-ZGA, and cpt1ab and cpt1b transcripts are almost completely degraded after this transition, cpt1a2b maintains low-level ubiquitous expression throughout gastrulation (shield to bud stages; Fig. 5 C-D). At the bud stage, a striking and specific upregulation of cpt1a2b expression emerges specifically within the prechordal plate mesendoderm—specifically in the polster cells (Fig. 5D, arrow), which is a critical domain for craniofacial organizer and absent in other paralogs.

Fig. 5. Spatiotemporal expression of cpt1a2b in zebrafish embryos.

Expression of cpt1a2b in (A) 1-cell stage embryos, (B) 512-cell embryos, (C) shield stage embryos, (D) bud stage embryos (the read triangle denotes the polster cells), (E) 24 hpf embryos, (F) 2 dpf embryos, (G) 3 dpf embryos (the read triangle denotes the pharyngeal endoderm) and (H) 4 dpf embryos. The read triangle denotes the pharyngeal endoderm. Scale bars: 200 µm.

cpt1a2b transcripts become restricted to the posterior trunk by 24 hpf (Fig. 5E), localizes exclusively to the pectoral fin bud by 2 dpf (Fig. 5F), suggesting potential roles in appendicular morphogenesis. Subsequent pharyngeal endoderm enrichment becomes evident from 3 dpf onward (Fig. 5 G-H). The progressively constrained spatiotemporal expression pattern of cpt1a2b suggesting that it may have a more specialized role in diverse developmental processes.

Differential expression of cpt1ab and cpt1b during heart regeneration

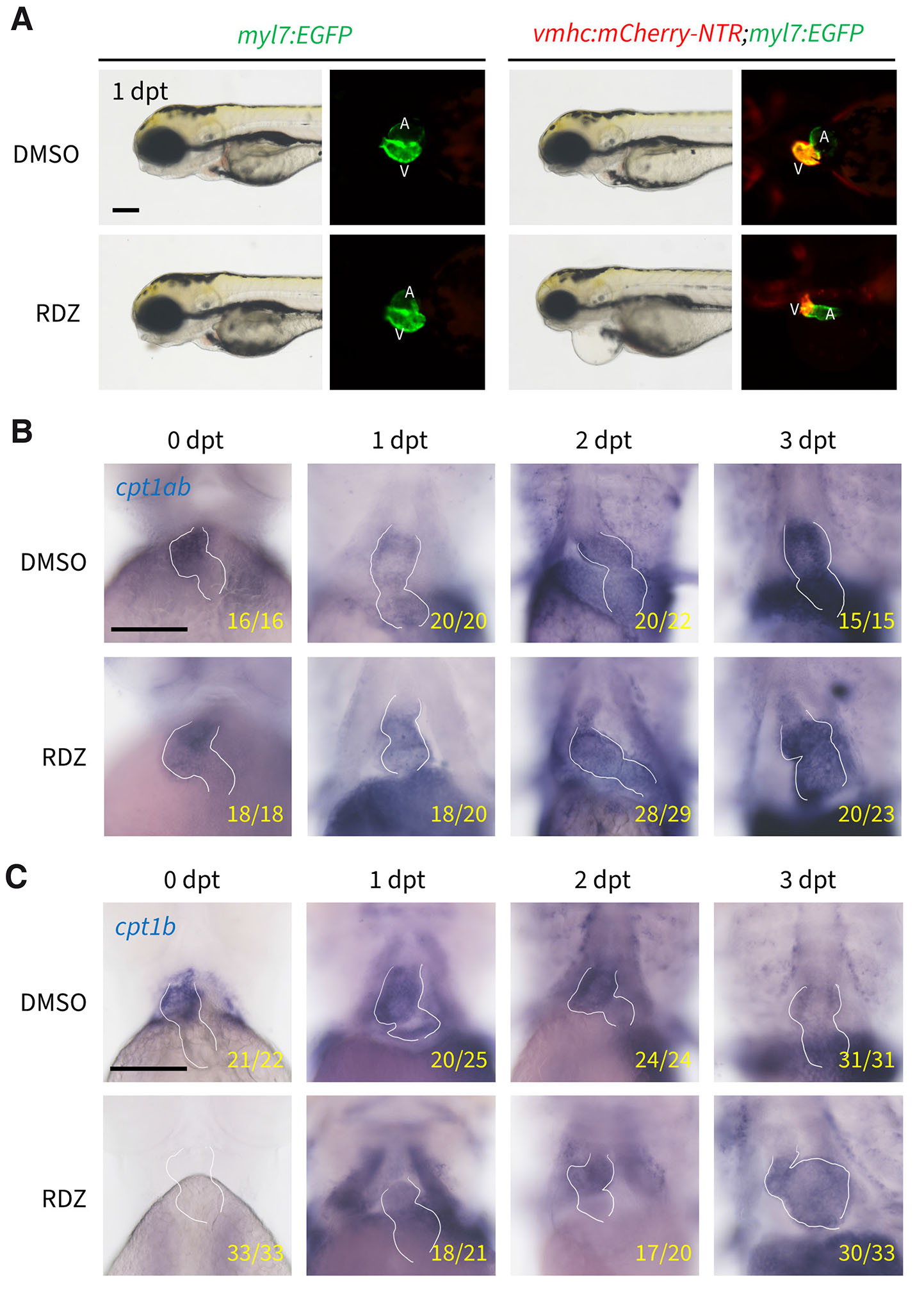

Zebrafish possess remarkable cardiac regenerative capacity, making them a valuable model for deciphering heart repair mechanisms. Previous studies established the Tg(vmhc:mCherry-NTR) zebrafish line for chemogenetic ventricular ablation, wherein the ventricular-specific myosin heavy chain (vmhc) promoter drives expression of a mCherry-nitroreductase (NTR) fusion protein to enable metronidazole (MTZ)-dependent cardiomyocyte ablation via prodrug conversion (Zhang et al., 2013). Ronidazole (RDZ) has been reported to induce target cell ablation at lower concentrations with reduced toxicity compared to MTZ (Lai et al., 2021). To validate RDZ as a suitable ablation prodrug for zebrafish hearts, we crossed the Tg(vmhc:mCherry-NTR) zebrafish to Tg(myl7:EGFP) zebrafish which expresses EGFP in all cardiomyocytes, and treated their offspring with RDZ since 36 hpf. RDZ treatment significantly reduced ventricular size and induced severe pericardial edema exclusively in Tg(vmhc:mCherry-NTR;myl7:EGFP) embryos, but not in Tg(myl7:EGFP) controls (Fig. 6A), confirming effective induction of ventricular cardiomyocyte ablation with RDZ.

Fig. 6. Differential expression dynamics of cpt1ab and cpt1b during zebrafish heart regeneration.

(A) Ronidazole (RDZ) treatment induces ventricular cardiomyocyte ablation. The embryos were imaged at 1 day post treatment (dpt). V, ventricle; A, atrium. (B) Whole-mount in situ hybridization shows temporal cpt1ab expression during zebrafish heart regeneration. (C) Temporal cpt1b expression during zebrafish heart regeneration. The white lines demarcate embryonic heart boundaries. Scale bars: 500 μm.

Given the cardiac expression of cpt1ab and cpt1b during development, we investigated their expression dynamics during heart regeneration. As shown in Fig. 6B, cpt1ab expression persisted post-ablation with no visible difference between DMSO- and RDZ-treated embryos, indicating minimal responsiveness to ventricular damage. In contrast, cpt1b expression was completely abolished after ablation, then gradually recovered from 1 day post-treatment (dpt) onward, reaching levels comparable to DMSO controls by 3 dpt (Fig. 6C). These data demonstrate that cpt1b, but not cpt1ab, exhibits dynamic expression changes in response to ventricular ablation, suggesting a potential role for cpt1b in zebrafish heart regeneration.

Discussion

This study presents the first comprehensive spatiotemporal expression study of the four cpt1 paralogs during zebrafish embryogenesis. While zygotic expression diverges markedly among these paralogs, their universal maternal expression indicates an indispensable role of cpt1 genes and fatty acid oxidation (FAO) in oogenesis and early developmental processes. This hypothesis aligns with extensive evidence demonstrating that pharmacological inhibition of FAO disrupts mouse oocyte maturation, early cleavage and blastulation, whereas enhanced FAO capacity improves mouse and yellow catfish oocyte quality and embryonic outcomes (Dunning et al., 2010; Li et al., 2021; Song et al., 2018). Given that FAO generates significantly more ATP compared to glycolytic metabolism, oocytes accumulate lipid reserves as an efficient energy source for embryonic growth (Paczkowski et al., 2013). The yolk, a lipid-rich structure, serves as a vital nutrient and energy reservoir for developing embryos. Following fertilization, most yolk lipids are hydrolyzed into fatty acids or packaged into lipoproteins within the yolk syncytial layer (YSL) and transported to the body of the developing embryos (Quinlivan and Farber, 2017); this process is essential for facilitating critical cell signaling and proliferation event required for organogenesis (Lv et al., 2018). In this context, maternally expressed cpt1 genes ensure adequate energy supply for fertilization and early cleavages.

The expression profiles of CPT1 family genes exhibit tissue- and organ-specific variability, with each paralog displaying a distinct distribution pattern (Wang et al., 2021). In human and mice, CPT1A is primarily expressed in the liver, with additional expression in the brain and heart, whereas CPT1B is predominant in skeletal muscle, heart, and adipose tissues (Schlaepfer and Joshi, 2020; Esser et al., 1996). Although both cpt1aa and cpt1ab are co-orthologs of mammalian Cpt1a with 77% amino acid conservation, the present study demonstrates that cpt1aa is predominantly expressed in the liver and transiently in the brain during early embryogenesis (Fig. 1), whereas cpt1ab exhibits a broader expression profile similar to that of cpt1b, including expression in the heart, muscle, and intestines (Figs. 3, 4). The distinct expression patterns between cpt1aa and cpt1ab strongly suggest that they have undergone substantial divergent subfunctionalization and/or neofunctionalization following TGD event ~320 million years ago (Li et al., 2020), although definitive attribution of these mechanisms requires careful comparative analysis with non-TGD vertebrates (Braasch et al., 2016; Thompson et al., 2021). Conversely, despite sharing only 53% protein sequence identity between cpt1ab and cpt1b, their share convergent expression patterns particularly in cardiac and somitic tissues; however, it remains unclear whether this similarity arises from coincidence or convergent evolution driven by natural selection. Regardless, this expression pattern similarity implies potential genetic complementation between cpt1ab and cpt1b, which should be taken into account in subsequent experiments.

The heart is highly reliant on FAO for energy production, particularly postnatally, which correlates with high Cpt1 expression levels in this organ. In the developing lamb and rat hearts, both Cpt1a and Cpt1b are expressed, with their expression levels fluctuating dynamically throughout development and postnatal growth (Bartelds et al., 2004; Lavrentyev et al., 2004). In neonatal mouse hearts, Cpt1b expression is significantly upregulated, accompanied by a marked increase in FAO activity, which is essential for hypertrophic growth and maturation of cardiomyocytes (Cao et al., 2019). Previous studies have shown that Cpt1 inhibition prevents ventricular wall thinning and slows the progression of heart failure during the early stages of myocardial infarction (MI) in dogs (Lionetti et al., 2005). More recent investigations have revealed that both Cpt1a and Cpt1b can promote mouse cardiomyocyte proliferation and enhance cardiac function post-MI (Li et al., 2023; Tang et al., 2025). In zebrafish, FAO and cpt1b have also been demonstrated to be essential for cardiomyocyte proliferation and ventricular regeneration (Zhao et al., 2024; Cheng et al., 2024). Consistent with these findings, the present study shows that both cpt1ab and cpt1b are expressed in the developing zebrafish heart. Ventricular ablation suppresses cardiac cpt1b expression without affecting cpt1ab levels, and cpt1b expression gradually returns to normal level as the zebrafish heart regenerates. These results suggest that Cpt1a and Cpt1b may exert both overlapping and distinct functions during cardiac regeneration. Further comparative analyses of Cpt1a and Cpt1b single mutants, as well as double mutants, are therefore necessary to clarify their differential roles in this process.

Materials and Methods

Zebrafish husbandry

All zebrafish used in this study were of the AB strain. Transgenic zebrafish lines used in this study were Tg(vmhc:mCherry-NTR) and Tg(myl7:EGFP). Adult zebrafish were maintained in a dedicated zebrafish breeding facility (ESEN Science & Technology, Beijing, China) under a diurnal light cycle of 14 hours of light and 10 hours of darkness. The fish were fed with artemia twice daily. The water temperature was consistently maintained at approximately 28°C, with a pH level of around 7.2 and a conductivity of approximately 500 μS/cm. Zebrafish embryos were obtained through natural mating and were cultivated in an incubator at 28.5°C. Zebrafish embryo staging followed the standard developmental timelines established by Kimmel et al., (1995) (Kimmel et al., 1995).

Phylogenetic analysis

Orthologous CPT1 sequences were identified through the Ensembl Comparative Genomics portal, leveraging orthology predictions from zebrafish cpt1 gene pages. Curated protein sequences for all analyzed species (Supplementary Data 1) underwent multiple sequence alignment using ClustalX 2.1 with default parameters. Phylogenetic reconstruction was performed via maximum-likelihood methodology implemented in ClustalX, followed by visualization and annotation using the Interactive Tree of Life platform (iTOL v7; https://itol.embl.de) (Letunic and Bork, 2024).

RNA probe synthesis

Zebrafish cpt1 cDNA fragments were amplified from an embryonic cDNA library using primers in Table 1. PCR products were cloned into a customized blunt-end cloning vector downstream of the T7 promoter. Positive clones were identified through colony PCR using T7 + gene-specific forward primers and validated by Sanger sequencing. Verified constructs were used to amplify templates for probe synthesis using T7 + forward primer pairs. Purified amplicons served as templates for in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase (M0251S, New England Biolabs, Ipswich, USA) and DIG RNA Labeling Mix (11277073910, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA). Riboprobes were purified by lithium chloride precipitation, resuspended in nuclease-free water, and stored at -80°C.

Table 1

Primers used to clone probe template for cpt1 genes

| Gene | Zfin Gene ID | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|---|

| cpt1aa | ZDB-GENE-060503-925 | AAAACCCTGTGGAGTCTCTG | TTGTTTCCGAAGCGATGAGA |

| cpt1ab | ZDB-GENE-030131-3250 | CACTGGACAGCTATGGCAAA | GATATCAAGCATCGCCTGTT |

| cpt1b | ZDB-GENE-041010-9 | GAAGCACATGGATACGATCC | GTGTCAATGAGATTGAGCTG |

| cpt1a2b | ZDB-GENE-050417-155 | GTCGTATTCCTGGTACGGTC | GCGTCATGGAAGCTTCATAT |

Whole mount in situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed as previously described (Thisse and Thisse, 2008). Zebrafish embryos at specified stages were dechorionated and fixed overnight with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA, P6148, Sigma-Aldrich), followed by dehydration using a graded series of methanol and stored at -20°C until use. For in situ hybridization, embryos were first rehydrated, permeabilized with proteinase K, and re-fixed with 4% PFA. After pre-hybridization, embryos were incubated with heat-denatured DIG-labeled riboprobes overnight at 65°C in hybridization buffer. Subsequently, unbound probes were thoroughly removed via sequential washes and embryos were blocked with blocking reagent prior to incubation with anti-DIG antibody solution (1:3000; 11093274910, Sigma-Aldrich) at 4°C overnight. Unbound antibody was removed by serial washing and signals were developed with NBT/BCIP solution. Reactions were closely monitored and stopped by PBS washes when optimal signal-to-background ratio was achieved.

Ventricular ablation

Ronidazole (RDZ, S4062, Selleck, Houston, USA) was dissolved in DMSO to a final concentration of 2 M and the stock solution was aliquoted and stored at -20°C. To ablate ventricular cardiomyocytes, 36 hpf Tg(vmhc:mCherry-NTR;cmlc2:EGFP) embryos were incubated with egg water containing either DMSO or 0.4 mM RDZ in dark for 18 hours. After ablation, the embryos were rinsed twice with fresh egg water and transferred to fresh egg water for further culture.

Imaging

To image the embryos, samples were rinsed with PBS solution, cleared in glycerol until they sank to the bottom, and mounted in glycerol on a double concave slide. Images were acquired with a Zeiss Zoom V16 stereomicroscope (Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with a Zeiss Axiocam 208 camera and Zen 3.1 software.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Ruilin Zhang (Wuhan University) and Prof. Dong Liu (Nantong University) for sharing the Tg(vmhc:mCherry-NTR) and Tg(myl7:EGFP) zebrafish lines and our laboratory members for critical comments and discussions.

Declarations

Author contributions

X.C. and Y.H. - conceptual and design of this study. X.C., W.H., C.K., Z.D., and H.C. - data collection and statistical analysis.Y.H. - manuscript preparation.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32070825), Jiangsu Double Innovation Talent Program (JSSCRC2021567) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20200865).

References

Bartelds B., Takens J., Smid G. B., Zammit V. A., Prip-Buus C., Kuipers J. R. G., van der Leij F. R. (2004). Myocardial carnitine palmitoyltransferase I expression and long-chain fatty acid oxidation in fetal and newborn lambs. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 286: H2243-H2248.

Braasch I., Gehrke A. R., Smith J. J., Kawasaki K., Manousaki T., Pasquier J., Amores A., Desvignes T., Batzel P., Catchen J., Berlin A. M., Campbell M. S., Barrell D., Martin K. J., Mulley J. F., Ravi V., Lee A. P., Nakamura T., Chalopin D., Fan S., Wcisel D., Cañestro C., Sydes J., Beaudry F. E. G., Sun Y., Hertel J., Beam M. J., Fasold M., Ishiyama M., Johnson J., Kehr S., Lara M., Letaw J. H., Litman G. W., Litman R. T., Mikami M., Ota T., Saha N. R., Williams L., Stadler P. F., Wang H., Taylor J. S., Fontenot Q., Ferrara A., Searle S. M. J., Aken B., Yandell M., Schneider I., Yoder J. A., Volff J.N., Meyer A., Amemiya C. T., Venkatesh B., Holland P. W. H., Guiguen Y., Bobe J., Shubin N. H., Di Palma F., Alföldi J., Lindblad-Toh K., Postlethwait J. H. (2016). The spotted gar genome illuminates vertebrate evolution and facilitates human-teleost comparisons. Nature Genetics 48: 427-437.

Britton C. H., Schultz R. A., Zhang B., Esser V., Foster D. W., McGarry J. D. (1995). Human liver mitochondrial carnitine palmitoyltransferase I: characterization of its cDNA and chromosomal localization and partial analysis of the gene.. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 92: 1984-1988.

Brown N. F., Weis B. C., Husti J. E., Foster D. W., McGarry J. D. (1995). Mitochondrial Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase I Isoform Switching in the Developing Rat Heart. Journal of Biological Chemistry 270: 8952-8957.

Cao T., Liccardo D., LaCanna R., Zhang X., Lu R., Finck B. N., Leigh T., Chen X., Drosatos K., Tian Y. (2019). Fatty Acid Oxidation Promotes Cardiomyocyte Proliferation Rate but Does Not Change Cardiomyocyte Number in Infant Mice. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 7: 42.

Cheng X., Ju J., Huang W., Duan Z., Han Y. (2024). cpt1b Regulates Cardiomyocyte Proliferation Through Modulation of Glutamine Synthetase in Zebrafish. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 11: 344.

Dunning K. R., Cashman K., Russell D. L., Thompson J. G., Norman R. J., Robker R. L. (2010). Beta-Oxidation Is Essential for Mouse Oocyte Developmental Competence and Early Embryo Development1. Biology of Reproduction 83: 909-918.

Esser V., Brown N. F., Cowan A. T., Foster D. W., McGarry J. D. (1996). Expression of a cDNA Isolated from Rat Brown Adipose Tissue and Heart Identifies the Product as the Muscle Isoform of Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase I (M-CPT I). Journal of Biological Chemistry 271: 6972-6977.

Ji S., You Y., Kerner J., Hoppel C. L., Schoeb T. R., Chick W. S.H., Hamm D. A., Daniel Sharer J., Wood P. A. (2008). Homozygous carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1b (muscle isoform) deficiency is lethal in the mouse. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 93: 314-322.

Kimmel C. B., Ballard W. W., Kimmel S. R., Ullmann B., Schilling T. F. (1995). Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Developmental Dynamics 203: 253-310.

Lai S., Kumari A., Liu J., Zhang Y., Zhang W., Yen K., Xu J. (2021). Chemical screening reveals Ronidazole is a superior prodrug to Metronidazole for nitroreductase-induced cell ablation system in zebrafish larvae. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 48: 1081-1090.

Lavrentyev E. N., He D., Cook G. A. (2004). Expression of genes participating in regulation of fatty acid and glucose utilization and energy metabolism in developing rat hearts. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 287: H2035-H2042.

Letunic I., Bork P. (2024). Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Research 52: W78-W82.

Li J., Liu L., Weng J., Yin T., Yang J., Feng H. L. (2021). Biological roles of l ‐carnitine in oocyte and early embryo development . Molecular Reproduction and Development 88: 673-685.

Li L.Y., Li J.M., Ning L.J., Lu D.L., Luo Y., Ma Q., Limbu S. M., Li D.L., Chen L.Q., Lodhi I. J., Degrace P., Zhang M.L., Du Z.Y. (2020). Mitochondrial Fatty Acid β-Oxidation Inhibition Promotes Glucose Utilization and Protein Deposition through Energy Homeostasis Remodeling in Fish. The Journal of Nutrition 150: 2322-2335.

Li X., Wu F., Günther S., Looso M., Kuenne C., Zhang T., Wiesnet M., Klatt S., Zukunft S., Fleming I., Poschet G., Wietelmann A., Atzberger A., Potente M., Yuan X., Braun T. (2023). Inhibition of fatty acid oxidation enables heart regeneration in adult mice. Nature 622: 619-622.

Lionetti V., Linke A., Chandler M., Young M., Penn M., Gupte S., Dagostino C., Hintze T., Stanley W., Recchia F. (2005). Carnitine palmitoyl transferase-I inhibition prevents ventricular remodeling and delays decompensation in pacing-induced heart failure. Cardiovascular Research 66: 454-461.

Lopes-Marques M., Delgado I. L. S., Ruivo R., Torres Y., Sainath S. B., Rocha E., Cunha I., Santos M. M., Castro L. F. C. (2015). The Origin and Diversity of Cpt1 Genes in Vertebrate Species. PLOS ONE 10: e0138447.

Lv Z., Fan H., Zhang B., Ning C., Xing K., Guo Y. (2018). Dietary genistein supplementation in laying broiler breeder hens alters the development and metabolism of offspring embryos as revealed by hepatic transcriptome analysis. The FASEB Journal 32: 4214-4228.

Melendez-Salcido C. G., Ramirez-Emiliano J., Garcia-Ramirez J. R., Gomez-García A., Perez-Vazquez V. (2025). Curcumin Modulates the Differential Effects of Fructose and High-fat Diet on Renal Damage, Inflammation, Fibrosis, and Lipid Metabolism. Current Pharmaceutical Design 31: 153-162.

Morash A. J., Le Moine C. M. R., McClelland G. B. (2010). Genome duplication events have led to a diversification in the CPT I gene family in fish. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 299: R579-R589.

Paczkowski M., Silva E., Schoolcraft W. B., Krisher R. L. (2013). Comparative Importance of Fatty Acid Beta-Oxidation to Nuclear Maturation, Gene Expression, and Glucose Metabolism in Mouse, Bovine, and Porcine Cumulus Oocyte Complexes1. Biology of Reproduction 88: 111.

Price N. T., van der Leij F. R., Jackson V. N., Corstorphine C. G., Thomson R., Sorensen A., Zammit V. A. (2002). A Novel Brain-Expressed Protein Related to Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase I. Genomics 80: 433-442.

Quinlivan V. H., Farber S. A. (2017). Lipid Uptake, Metabolism, and Transport in the Larval Zebrafish. Frontiers in Endocrinology 8: 319.

Schlaepfer I. R., Joshi M. (2020). CPT1A-mediated Fat Oxidation, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Potential. Endocrinology 161: bqz046.

Shen Y., Xu X., Yue K., Xu G. (2015). Effect of different exercise protocols on metabolic profiles and fatty acid metabolism in skeletal muscle in high-fat diet-fed rats. Obesity 23: 1000-1006.

Song Y.F., Tan X.Y., Pan Y.X., Zhang L.H., Chen Q.L. (2018). Fatty Acid β-Oxidation Is Essential in Leptin-Mediated Oocytes Maturation of Yellow Catfish Pelteobagrus fulvidraco. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 19: 1457.

Tang L., Shi Y., Liao Q., Wang F., Wu H., Ren H., Wang X., Fu W., Shou J., Wang W. E., Jose P. A., Yang Y., Zeng C. (2025). Reversing metabolic reprogramming by CPT1 inhibition with etomoxir promotes cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart regeneration via DUSP1 ADP-ribosylation-mediated p38 MAPK phosphorylation. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 15: 256-277.

Thisse C., Thisse B. (2008). High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nature Protocols 3: 59-69.

Thompson A. W., Hawkins M. B., Parey E., Wcisel D. J., Ota T., Kawasaki K., Funk E., Losilla M., Fitch O. E., Pan Q., Feron R., Louis A., Montfort J., Milhes M., Racicot B. L., Childs K. L., Fontenot Q., Ferrara A., David S. R., McCune A. R., Dornburg A., Yoder J. A., Guiguen Y., Roest Crollius H., Berthelot C., Harris M. P., Braasch I. (2021). The bowfin genome illuminates the developmental evolution of ray-finned fishes. Nature Genetics 53: 1373-1384.

Ulhaq Z. S., Ogino Y., Tse W. K. F. (2023). Deciphering the pathogenesis of retinopathy associated with carnitine palmitoyltransferase I deficiency in zebrafish model. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 664: 100-107.

Wang M., Wang K., Liao X., Hu H., Chen L., Meng L., Gao W., Li Q. (2021). Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase System: A New Target for Anti-Inflammatory and Anticancer Therapy?. Frontiers in Pharmacology 12: 760581.

Wolfgang M. J., Kurama T., Dai Y., Suwa A., Asaumi M., Matsumoto S., Cha S. H., Shimokawa T., Lane M. D. (2006). The brain-specific carnitine palmitoyltransferase-1c regulates energy homeostasis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103: 7282-7287.

Yamazaki N. (2004). Identification of Muscle-Type Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase I and Characterization of Its Atypical Gene Structure. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 27: 1707-1716.

Zecchin A., Wong B. W., Tembuyser B., Souffreau J., Van Nuffelen A., Wyns S., Vinckier S., Carmeliet P., Dewerchin M. (2018). Live imaging reveals a conserved role of fatty acid β-oxidation in early lymphatic development in zebrafish. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 503: 26-31.

Zhang R., Han P., Yang H., Ouyang K., Lee D., Lin Y.F., Ocorr K., Kang G., Chen J., Stainier D. Y. R., Yelon D., Chi N. C. (2013). In vivo cardiac reprogramming contributes to zebrafish heart regeneration. Nature 498: 497-501.

Zhao Y., Lv H., Yu C., Liang J., Yu H., Du Z., Zhang R. (2024). Systemic inhibition of mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation impedes zebrafish ventricle regeneration. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 1870: 167442.