Int. J. Dev. Biol. 69: 133 - 142 (2025)

Comprehensive analysis of Ephrin ligand and receptor expression reveals exclusive domains during nephrogenesis for epha4/epha7 and efna3

Open Access | Developmental Expression Pattern | Published: 13 October 2025

Abstract

Interactions between ephrins and their Eph receptors regulate a broad range of cellular processes, including attraction, repulsion, adhesion and migration, all of which play crucial roles in tissue remodeling and homeostasis. While several ephrin ligands and Eph receptors are known to be expressed in the developing kidney, their specific roles, particularly during nephrogenesis, remain poorly understood. The development of the Xenopus pronephros provides an accessible and relatively simple model for studying vertebrate nephrogenesis. Through a comprehensive gene expression analysis of all ephrin ligands and Eph receptors present in Xenopus genomes, we have identified members of the Eph-ephrin signaling pathway that may contribute to pronephric development. Among them, efna3, which encodes an ephrin ligand, is strongly expressed in the ventral region of the pronephric anlage and later in the intermediate and distal segments of the developing tubule. This expression pattern is strikingly complementary to that of epha4 and epha7, which are expressed in the region forming the proximal tubule. This suggests a potential role for efna3-epha4/epha7 signaling in establishing a boundary between these domains during pronephros development.

Keywords

Nephron, Xenopus embryo, ephrins, eph receptors, pronephros

Introduction

The kidney plays a central role in fluid filtration, solutes absorption, excretion, and blood homeostasis. In vertebrates, kidney development proceeds through three stages: pronephros, mesonephros and metanephros (Saxén and Sariola, 1987). Despite their increasing complexity, they all share the nephron as a structural and functional basic unit. While the pronephros is rudimentary and non-functional in mammals, it serves as the functional kidney in amphibian tadpoles. It is made up of three components: the glomus that ensures blood filtration, the tubule where salts and macromolecules absorption take place, and the duct that connects to the cloaca. Similar to the mammalian metanephros, the tubule is divided into proximal, intermediate and distal segments, each performing specific physiological functions (Desgrange and Cereghini, 2015; Raciti et al., 2008). Given the conservation of kidney development in vertebrates, the functional Xenopus laevis (African clawed frog) pronephros offers a simplified model for nephrogenesis. The development of the Xenopus pronephros begins at the early neurula stage in the intermediate mesoderm, with the emergence of the kidney field characterized by the overlapping expression of the key transcription factors pax8 and lhx1 (Buisson et al., 2015; Carroll and Vize, 1999; Cirio et al., 2011). At the early tailbud stage, cells in the somatic layer begin to segregate from the remaining intermediate mesoderm and form the pronephric anlage, which can be visualized externally as a bulge positioned ventrally to the anterior somites. These cells will give rise to the segmented tubule whereas cells in the adjacent medial layer will form the glomus. Several transcription factors including hnf1b, irx genes and evi1/mecom have been implicated in tubule segmentation (Alarcón et al., 2008; Buisson et al., 2015; Desgrange and Cereghini, 2015; Heliot et al., 2013; Reggiani et al., 2007; Van Campenhout et al., 2006). Tubule elongation involves convergent extension movements (Lienkamp et al., 2010). Live imaging revealed that two opposing morphogenetic cell movements shape the primary loop which continues to form the intermediate segment (Lienkamp et al., 2010). Inversin and Frizzled-8 control the dorsal to ventral movement of the proximal cells while signaling pathways for the posterior to anterior movement in the distal pronephros remain unclear (Lienkamp et al., 2010). As the pronephric tubule extends toward the posterior, it meets the anterior migrating rectal diverticulum allowing connection to the cloaca. A functional pronephric kidney is complete at tadpole stage 35/36, two days after fertilization.

Eph-ephrin signaling is essential for short-distance cell-to-cell interactions, regulating cellular behaviors such as attraction, repulsion, adhesion or migration. It plays major roles in tissue remodeling and maintenance in both the embryo and adult (Kania and Klein, 2016). The signaling involves the binding of transmembrane Eph receptors to membrane-bound ephrin ligands (Taylor et al., 2017). In addition to classical forward signaling through tyrosine kinase Eph receptors via oligomerization, autophosphorylation and phosphorylation of intracellular substrates, reverse signaling can also occur in cells expressing ephrin ligands (Weiss and Kispert, 2016). Two classes of ephrin ligands have been described. Class A ephrins have an extracellular globular domain tethered to the membrane with a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor, while class B ephrins are transmembrane proteins with a short intracellular domain. EphA receptors generally interact with class A ephrins, while EphB receptors interact with class B ephrins, although some exceptions exist (e.g. ephrinB2 also binds to EphA4 and A7 (Weiss and Kispert, 2016)).

A total of fourteen human Eph receptors are encoded by EPHA1-8, EPHA10, EPHB1-4 and EPHB6 genes, while eight ephrin ligands are encoded by EFNA1-5 and EFNB1-3 (Taylor et al., 2017). Every human gene encoding ephrin ligands has an ortholog in Xenopus laevis and Xenopus tropicalis genomes, as do most of the Eph receptors, with the exception of EPHA1 and EPHB6 (https://www.xenbase.org/xenbase/, (Fisher et al., 2023)). While X. tropicalis is a diploid species, X. laevis is allotetraploid. Nine sets of homeologous chromosomes have been identified in X. laevis, eight corresponding to the chromosomes 1-8 in X. tropicalis, while the last set corresponds to a fusion of chromosomes 9 and 10 of X. tropicalis. Every set of X. laevis homeologous chromosomes has a long (L) and a short (S) chromosome (Matsuda et al., 2015). The homeologous .L subgenome generally appear to have retained the ancestral condition, while the .S subgenome evolved asymmetrically, being more disrupted by deletion and rearrangement (Session et al., 2016). As a consequence, every Xenopus ephrin or eph receptor ortholog has a .L homeolog in X. laevis, while a .S homeolog can be missing as for example for efnb1 for which only efnb1.L is present (https://www.xenbase.org/xenbase/, (Fisher et al., 2023)).

Eph-ephrin signaling is involved in key processes during Xenopus development including gastrulation, retinal progenitor migration in the eye field, hindbrain formation, angiogenesis, development of the pronephros and otic vesicle (Fagotto, 2020; Helbling et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2006; Sun et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2020). This has greatly benefited from the experimental advantages offered by the Xenopus embryo for analyzing Eph–ephrin signaling at a mechanistic level (Hwang and Daar, 2017), as exemplified by studies on the formation of the ecto–mesodermal boundary at Brachet’s cleft during gastrulation involving Epha4/Ephb4 receptors and Efnb2/Efnb3 ligands (Barua and Winklbauer, 2022; Fagotto, 2020).Two Eph receptors are known to be expressed in the developing pronephros. EphA7, specifically expressed in the proximal tubule at tadpole stages, regulates tubule cell adhesion by modulating the tight junction protein claudin6. In cultured cells, ephA7 binds and phosphorylates claudin6 (CLDN6), reducing its cell surface distribution (Sun et al., 2018). Interestingly, a soluble form of ephA7 antagonizes ephA7 full length (EphA7-FL), stabilizing Claudin6 (CLDN6) at the membrane. Nicalin, a Nicastrin-like protein (Wang and Wang, 2021) binds the soluble form of epHA7, limiting its secretion and preventing the formation of EphA7 complex. EphA4 is also expressed in the proximal part of the developing pronephric tubule, but its function has not been investigated (Smith et al., 1997; Van Campenhout et al., 2006). Whether these Eph receptors interact with an ephrin ligand in the developing pronephros, and if so, which ephrin, remains unknown.

Eph-ephrin signaling is also crucial in kidney and urinary tract development in mammals (Weiss and Kispert, 2016). In mice, EphA4 and EphA7 are essential for nephric duct insertion to the cloaca (Weiss et al., 2014). EfnB1 is expressed during formation of the slit diaphragm of the glomerular podocyte (Hashimoto et al., 2007) and Nephrin/EfnB1/NHERF2 complex can bind ezrin and actin leading to podocyte healing (Fukusumi et al., 2021).

Given the complexity of the families of ephrin ligands and Eph receptors, it is important to have a comprehensive view of which of their members are expressed during renal development. As outlined above, the developing Xenopus pronephros is an accessible and relatively simple model of vertebrate nephrogenesis. We have therefore analyzed the expression of every gene encoding members of the ephrin/Eph families to identify those whose expression might prompt potential functions during the development of the nephron. Efna3 encoding an ephrin ligand has a ventral expression domain in the developing pronephros that is complementary to a dorsal domain where genes encoding receptors epha4 and a7 are expressed, suggesting a role in the maintenance of a boundary between these domains.

Results and Discussion

Expression of ephrins and Eph receptors at the early tadpole stage (St35/36) in the pronephros

In an initial attempt to identify eph and efn family genes expressed in the pronephric nephron, we analyzed the expression of each member using whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) at the early tadpole stage (st35/36), when nephrogenesis is nearly completed (Fig. 1, Table 1). We therefore cloned cDNAs corresponding to all eph and efn family genes to synthesize riboprobes. Primer sequences used for RT-PCR were designed based on the .L homeologs (Table 2). Both .L and .S homeologs are present in the genomic data as gene models for each member of the eph and efn gene families, except for efnb1 where only efnb1.L is present (www.xenbase.org, (Fisher et al., 2023)). Some .S homeologs are expressed in oocytes or embryos at very low levels compared to their .L counterparts (efna5, epha8), or not at all (efna3, epha10) (Session et al., 2016). For other eph and efn genes, the .L and .S homeologs show high sequence similarity, making it likely that the riboprobes detect the expression of both homeologs in these cases.

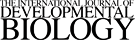

Fig. 1. Expression of genes encoding the members of the Eph-ephrin signaling components in the pronephros at early tadpole stage 35/36.

The enlarged region corresponding to the pronephric region is shown with a general view of the tadpole. (A) Genes encoding ephrin ligands. Expression of efna3 and b2 is detected in the developing pronephros; efna3 is expressed in the intermediate and distal segments of the tubule (It, Dt). Expression of efnb2 is observed in the glomus region (G). Expression of efna5 and b1 is detected at the level of the vessels associated with the pronephros: in the pronephric sinus (Ps), the posterior cardinal vein (Pcv), the common cardinal vein (Ccv) and the intersomitic veins (Iv). Efna5 expression is also observed in the heart (H). Efna1 seems to be weakly expressed in the pronephric sinus and intersomitic vein. Scale bars: 0.8 mm for whole embryo and 0.3 mm for embryo magnification. (B) Genes encoding Eph receptors. Expression of epha4, a7, b3 and b2 are clearly detected in the pronephros. Epha4 and EphA7 are expressed in the PT1, PT2 and PT3 segments of the proximal tubule (Pt1, three lines, Pt2, line and Pt3 arrowhead) while ephb3 is detected only in PT3 (arrowhead). Ephb2 is detected in the proximal, intermediate and the first distal segment of the tubule. No pronephric expression of epha2, a3, a5, a6, a8, a10 and b1 is observed. Expression of ephb4 is detected in the vessels associated with the pronephros. Pt, It, Dt: proximal, intermediate and distal tubule. Scale bars: 1.7 mm for whole embryo and 0.5 mm for embryo magnification.

Table 1

Ephrin and Eph receptor-encoding gene expression in the pronephros in early tadpoles (st35/36)

| Gene | Pronephric expression | Commentsa | Referenceb |

|---|---|---|---|

| efna1 | NO | Vascular expression | |

| efna2 | NO | ||

| efna3 | YES | IT+DT | |

| efna4 | NO | ||

| efna5 | NO | vascular expression | |

| efnb1 | NO | vascular expression | (Costa et al., 2003; Giudetti et al., 2014) |

| efnb2 | YES | Glomus | (Helbling et al., 2000; Kirmizitas et al., 2017) |

| efnb3 | NO | ||

| epha2 | NO | vascular expression | |

| epha3 | NO | vascular expression | |

| epha4 | YES | PT1+PT2+PT3 | (Barnett et al., 2012; Rothe et al., 2017; Smith et al., 1997; Winning and Sargent, 1994; Xu et al., 1995) |

| epha5 | NO | vascular expression | |

| epha6 | NO | vascular expression | |

| epha7 | YES | PT1 +PT2+PT3 | (Wang et al., 2016) |

| epha8 | NO | vascular expression | |

| epha10 | NO | Migrating hypaxial myoblasts | |

| ephb1 | NO | vascular expression | (Helbling et al., 2000; Smith et al., 1997) |

| ephb2 | YES | Prominent in IT1 | (Helbling et al., 2000) |

| ephb3 | YES | Exclusively in PT3 | (Helbling et al., 2000) |

| ephb4 | NO | vascular expression | (Cheong et al., 2006; Helbling et al., 2000) |

Genes expressed in the pronephros appear in bold. aAdditional comments about pronephric or mesodermal expression. bReferences about previously published gene expression data at early tadpole stage when available. IT1,2: intermediate tubule segments 1 or 2. PT1,2,3: proximal tubule segments 1, 2 or 3.

Table 2

Sequence of primers used for cDNA cloning of the different members of efn and eph gene members with the corresponding accession numbers

| Gene | Forward | Reverse | Accession |

| efna1.L | 5’- ACGAGACCTGCAAGCCCAT-3’ | 5’- ACAGGGCTAGGTGGGTTAAAGTC-3’ | NM_001095329 |

| efna2.L | 5’- TCTGTGGCACTGCCAGAAGT -3’ | 5’- TGGTGAAGATAGGCTCTGGAGACT-3’ | XBmRNA2762 |

| efna3.L | 5’- GCCAACAGGCACTCGGTCTA-3’ | 5’- CTCTGCCATATCCCGAGGG -3’ | XM_018231573 |

| efna4.L | 5’- CCTGAAGCTGCGGGTGTCT -3’ | 5’- GAGCCACTTGGGAATGAGCA -3’ | NM_001127882 |

| efna5.L | 5’-CCACACCTTCTATTACATGCCTACA-3’ | 5’-ATGGGCGCAGGCACC-3’ | XM_018264443 |

| efnb1.L | 5’- CGGCGCTGGGAAAGAACT-3’ | 5’- TGATGTCACTGGGTTCGCTG-3’ | NM_001087479 |

| efnb2.L | 5’- TGGGATACAGTGCATGTGAGC-3’ | 5’- TGCGTTTTGGAGTGGCTAATG-3’ | NM_001086485 |

| efnb3.L | 5’- TTAATCAGCATGTTTTCCCGG-3’ | 5’- AGTGAGGGCAAAAGGCACC-3’ | NM_001085842 |

| epha2.L | 5’-GAGAACTTGGCTGGCTCACC-3’ | 5’-GGCCTCTGGCGCACACT-3’ | NM_001087611 |

| epha3.L | 5’-ACGAGACTGCAACAGTATCCCTC-3’ | 5’-GAGCCGCCTGGTTCGTAGT-3’ | XBmRNA11892 |

| epha4.L | 5’- TGCACTATAGCCCCCAGCA-3’ | 5’- CCGACCATCATTCTTCCGAA-3’ | NM_001085992.1 |

| epha5.L | 5’- GGGAAGAAATTGGAGAGGTAGATG -3’ | 5’- AGCCATTCACCTTCTGCACTG - 3’ | XM_031903379.1 |

| epha6.L | 5’- AGCTGTCCATGAGTTTGCCAA -3’ | 5’- CCACGTCCAGCGTTGTGA – 3’ | XBmRNA11875 |

| epha7.L | 5’-TCAAGTCTTGGAGCCCAACC-3’ | 5’-GGGCAACAAGGTCCACAATG-3’ | XM_031902278 |

| epha8.L | 5’- CCCCCAACAGATGAGCCTAG-3’ | 5’- TGTTAAACTGCCCATCCCGA - 3’ | XM_018241840 |

| epha10.L | 5’- TCCACCTAATGGATGGGAGG -3’ | 5’- TGACCTGACTGGCCCTGAA – 3’ | XM_018246715 |

| ephb1.L | 5’-CACGGCAGTTGGGTTTGACT-3’ | 5’-CCCATCGTTTTGCCGTAGAA-3’ | XM_018265884 |

| ephb2.L | 5’-GGGTACACGGAGAAACAGCG-3’ | 5’-GGAAGCGCCAATCAAACTTC-3’ | XM.0182241849 |

| ephb3.L | 5’- TGGCGGTAGTTCGGTCTGTT-3’ | 5’ ACGTGGAGCTGAGGGCAC-3’ | XM_018262082 |

| ephb4.L | 5’- CTCTTCGCATAGGGCCCC-3’ | 5’- CTCAAGCAGATGGGCCTCAT-3’ | NM_001136172 |

Note that due to sequence conservation between the two homeologs, probes generated from the amplified sequences may detect expression of both.

Many of eph and efn family genes are expressed at high levels in the head region, particularly in the developing brain, neurogenic placodes, visceral skeleton and eye. Since we needed to detect lower expression levels in the pronephric nephron, we had to overstain the head in several instances. Only one gene encoding class A ephrin ligands is expressed in the pronephros: efna3 along with efnb2 among class B ligands (Fig. 1). Efna3 expression is remarkably prominent in the intermediate and distal segments of the pronephric tubule and has never been described previously. It will be studied in detail in the next paragraph (Figs. 2, 3). Efnb2 is expressed at the level of the developing glomus in a region containing differentiating podocytes (Fig. S2). At stage 35/36, some genes encoding subfamily A of Eph receptors are detected in pronephros area: epha4, and epha7. As expected, epha4 and epha7 are expressed in the proximal part of the pronephric tubule. Two ephb genes are expressed at stage 35/36 in the pronephros: ephb2 and ephb3. The former is detected in intermediate and distal segments and poorly expressed in proximal region, while the latter has a more restricted expression in the PT3 region of the proximal tubule (Figs. 1, 4).

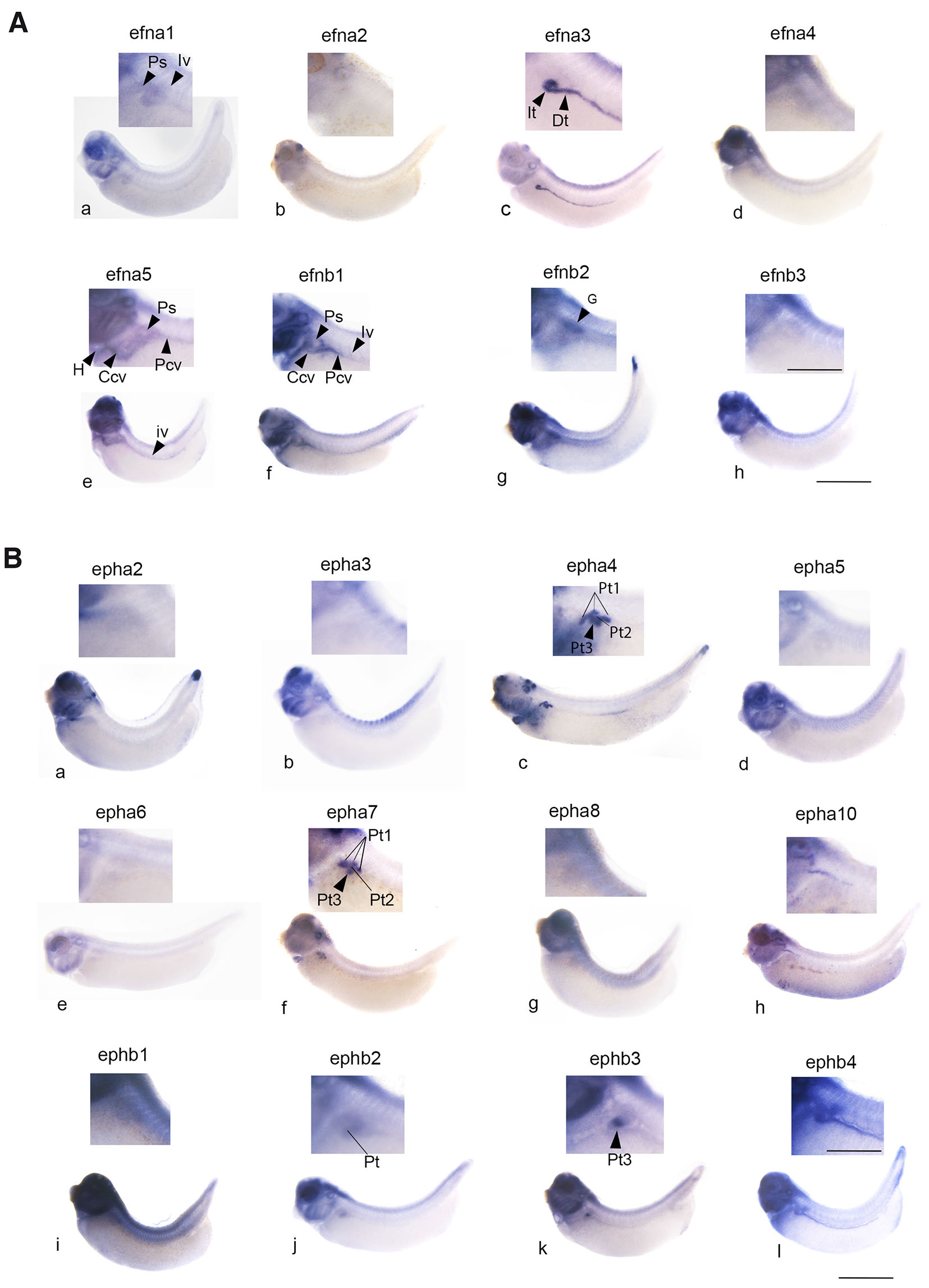

Fig. 3. Expression of efna3 at stages of pronephric development.

WISH analysis at stages ranging from early neurula stage 14 (appearance of the kidney field) to early tadpole stage 35/36 (functional pronephros). Anterior, dorsal and lateral views are shown at neurula stages (st14 and 20). Lateral and dorsal views are shown at tailbud stage 25. Only lateral views are shown for tailbud stages 28 and 32, and early tadpole (st35/36). At stage 14, 20 and 25, images of sectioned embryos are shown with red dotted lines, indicating the corresponding levels on whole mounts. For convenience, these levels are just indicated with arrows 1, 2, and 3 at stage 28, 32 and 35/36 (note that the sections were not made from the whole mount specimen shown). Efna3 starts to be detected in the developing tubule from the stage 28. It is detected prior to stage 28 in the developing nervous system and migrating cephalic neural crest cells. Efna3 is expressed at stage 14 in the primary neuronal precursors (Np), and weakly in the anterior neural folds (Nf). Neural expression expands at st20 to the closing neural tube (Nt). It is strong in the emerging first (n1) and third/fourth (n3, n4) branchial arches neural crest streams. Cg: cement gland. At stage 25, efna3 expression is strong in branchial neural crest streams populating the first arch around the eye rudiment (n1), as well as the third and fourth arches (n3, n4). It is also detected in the dorsal neural tube (Nt). Efna3 is also expressed in the proctodeal region (Pr). At stage 28, efna3 is now expressed in the ventral region of the pronephric anlage (red arrowhead). It is detected in the dorsal region of the midbrain (Mb) and in the hindbrain (Hb), as well as in the developing branchial arches (Ba). In addition to the first branchial arch around the eye (n1), and the third and fourth branchial arches (n3, n4), efna3 is now also detected in the second branchial arch (n2). Expression of efna3 is observed in developing neural placodes, in the epidermis overlying the optic vesicle that contains the lens placode (Lp), in the ventral region of the otic vesicle (Ov) and in the developing posterior lateral line placode (Pp, blue arrowhead). Efna3 is also detected in the proctodeal region (Pr). Pronephric expression at stage 32 is very strong in a region of the tubule at the origin of the intermediate and distal segments (red arrowhead). Efna3 continues to be detected in the anterior midbrain (Mb) and in a hindbrain (Hb) region likely corresponding to rhombomere 4. It continues to be detected in the four branchial arches (n1, n2, n3 and n4), in the posterior lateral line placode and in the otic vesicle (Ov). It is now expressed in the developing lens (L). Expression at stage 35/36 is similar to stage 32 in the intermediate and distal segments of the developing tubule (It, Dt). Expression is diminishing in the branchial arches (Ba) and the hindbrain (Hb) but is very strong in dorsal midbrain (Mb), otic vesicle (Ov), and lens (L). Scale bar: 1.7 mm for whole embryo, 0.5 mm for embryonic magnification and 280 μm for section.

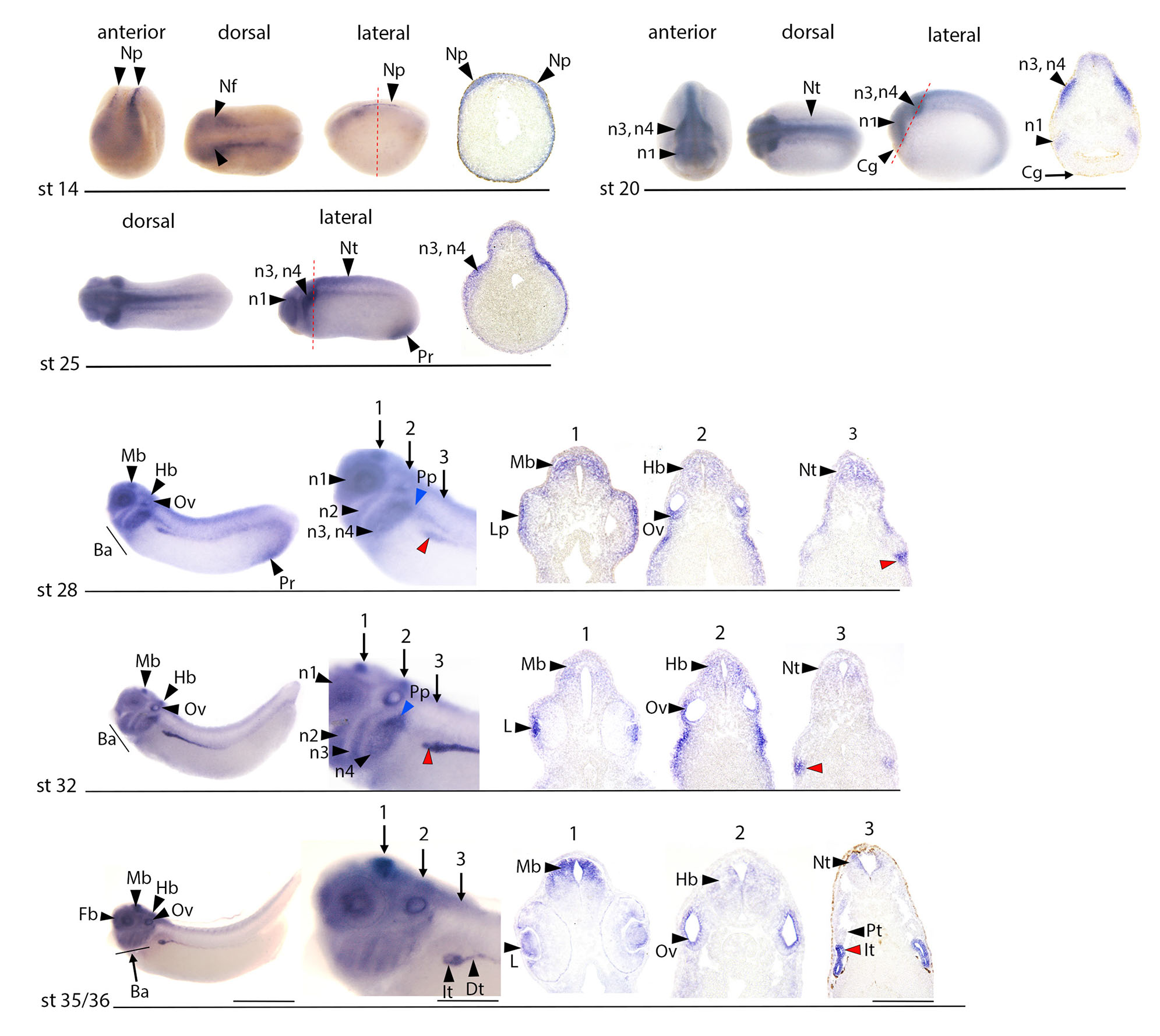

Fig. 4. Expression of Eph receptors epha4, a7, b2 and b3 at stages of pronephric development.

WISH analysis at stages ranging from neurula stage 14-18 (kidney field) to early tadpole stage 35/36 (functional pronephros). Anterior, dorsal and lateral views are shown at neurula stages (st14-18 and 20). Only lateral views are shown for tailbud stages 25, 28 and 32, and early tadpole (st35/36). Images of sectioned embryos at stage 35/36 are shown, with red dotted lines, indicating the corresponding levels on whole mounts (note that the sections were not made from the whole mount specimen shown). Pronephric expression of epha4, a7 and b2 is detected from stage 25 onward, while ephb3 is only detected in the pronephros at stage 32. Epha4 and a7 are mostly co-expressed in the dorsal region of the pronephric anlage at stages 25 and 28. Their expression is maintained in the emerging PT1 segments at stage 32 (blue arrowheads) and expands at stage 35/36 in PT2 (line) and PT3 (arrowhead). EphA4 is also expressed in connecting tubule (Ct). Expression of ephb2 is observed in the whole anlage at stages 25 and 28, and later in the developing tubule especially in intermediate region (It), while ephb3 transcripts are detected in the PT3 segment at stages 32 and 35/36. Expression of epha4 in the developing central nervous system (Fb, Mb, r3, 5: rhombomeres 3 and 5; cephalic neural crest n3: neural crest destined for third arch), developing heart (h) and tailbud (Bc) confirms previously published observations (Barnett et al., 2012; Rothe et al., 2017; Smith et al., 1997; Winning and Sargent, 1994; Xu et al., 1995), as well as epha7 expression in forebrain (Fb) and hindbrain (Hb), Cement gland (Cg), otic vesicle (Ov) and developing heart (H) (Wang et al., 2016). Ephb2 expression at neurula stage is observed in the anterior neural plate. At stage 20, it is observed in the whole neural tube and in the optic placode (Op), and at lower levels in the cement gland (Cg). It is detected at tailbud stage in the developing eye and migrating neural crest cells populating every branchial arch. Expression of ephb3 at neurula stage is principally observed in the cement gland (Cg) and also at low levels of expression in the neural plate. At tailbud stages 25 and 28, it is detected in the developing eye, midbrain and with a segmented pattern in the hindbrain, and at lower levels in migrating cephalic neural crest. Strong ephb3 expression is detected in the fourth branchial arch at stages 32 and 35/36 (n4). The red arrowheads indicate the pronephric anlage at stages 25 and 28, and the pronephros at stage 32 and 35/36. Scale bar: 1.7 mm for whole embryo, 0.5 mm for embryonic magnification and 280 μm for section.

Some genes encoding ephrin ligands or Eph receptors may be expressed only transiently in the developing pronephros, making them undetectable at stage 35/36. To address this possibility, we performed additional WISH analyses at earlier stages (Figs. S1–4) to complement the data shown in Fig. 1. Some members of the ephrin–Eph receptor family are expressed in the pronephric region but appear to be localized specifically to the developing nephron vasculature. This is the case of efna1, efna5 (Fig. S1), efnb1 (Fig. S2), epha2, epha3, epha5, epha6 (Fig. S3) and epha8 (Fig. S4). Vascular expression of ephb4 has been previously documented (Helbling et al., 2000). Additionally, while epha10 is not detected in the pronephros at stage 35/36, instead being expressed in migrating hypaxial myoblasts and the eye, it is present at low levels in the developing pronephros at tailbud stages 25, 28, and 32 (Fig. S4).

Expression of efna3 and epha4/a7 at tailbud stage map complementary domains of the pronephric anlage

The Eph-ephrin signaling pathway plays a crucial role in tissue boundary formation. EfnA3 and EphA4 have been often observed to be distinctly expressed in certain tissues where they mediate repulsive interactions. In mammals for example, such interactions are essential for the migration of cortical interneurons in the basal telencephalon (Rudolph et al., 2010) and for hippocampal dendritic spine formation (Bourgin et al., 2007; Murai et al., 2003). EfnA3 has also been implicated in axonal guidance through its interaction with the EphA4 receptor (Steinecke et al., 2014).

As outlined above, efna3 is only poorly characterized in Xenopus. According to Xenbase data (Fisher et al., 2023), only the homeologue L is expressed in Xenopus laevis (Session et al., 2016). The deduced amino sequence is strongly conserved in vertebrates (Fig. 2A), particularly in tetrapods (Fig. 2B), sharing 68.2% and 68.4% identity with the human and mouse sequences, respectively.

We further studied how efna3 is expressed during the development of the pronephros, from the early neurula stage (st14), when the pronephric field is established, to the early tadpole stage (st35/36) (Fig. 3), and have compared these observations with the expression patterns of eph receptors-encoding genes expressed in the pronephric tubule, not only epha4, but also epha7, ephb2 and ephb3 (Fig. 4).

Efna3 is detected in the developing tubule from the tailbud stage 28 (Fig. 3), but is expressed earlier in other tissues. At early neurula stage 14, efna3 expression is observed in the primary neuronal precursors and weaker in the anterior neural plate. Its neural expression expands at neurula stage 20 to a large part of the neural tube, with strongest expression in the emerging first and third branchial neural crest streams (Fig. 3). No Eph receptor is detected in the developing pronephros at these stages.

At the tailbud stage 25, efna3 is highly expressed in migrating neural crest populating the third and fourth branchial arches. It is also detected around the eye vesicle in migrating neural crest cells of the first branchial arch, and in the developing midbrain, posterior hindbrain and spinal cord. Expression is also observed in the proctodeal region. At this stage, efna3 is not expressed in the developing pronephros, but receptors epha4 and a7 are strongly expressed in the dorsal region of the pronephric anlage. Ephb2 expression is also detected, although at lower levels. No detectable expression of ephb3 can be observed (Fig. 4).

At tailbud stage 28, efna3 is clearly expressed in the ventral region of the pronephric anlage (Fig. 3). Its expression persists in the proctodeal region, the developing nervous system and branchial arches. In addition to being detected in the first and third/fourth arches, efna3 is now expressed in the second arch. High levels of expression are observed in the ventral region of the otic vesicle and in the epidermis overlying the optic vesicle, including the lens placode. Efna3 is detected ventrally to the otic vesicle in the developing posterior lateral line placode (Schlosser, 2003; Schlosser and Northcutt, 2000). Strong expression is also observed in the anterior midbrain. Epha4 and a7 are co-expressed in the dorsal region of the pronephric anlage with highest intensities in the three nephrostomes-forming regions (Fig. 4). Ephb2 expression is detected in a wider area comprising most of the developing pronephros. Ephb3 is not detected in the pronephros (Fig. 4).

Efna3 expression at late tailbud stage 32 is similar to st28, with the exception of the proctodeal region where it is no more detected. Efna3 is strongly expressed in the ventral region of the pronephric anlage at the origin of the intermediate and distal segments of the tubule. Expression in developing branchial arches and anterior midbrain persists. It is strong in a region of the hindbrain immediately above the otic vesicle that likely corresponds to the rhombomere 4, as well as in the developing posterior lateral line placode. It is also strongly detected in the developing lens. Eph receptors epha4, a7, b2 and b3 are all expressed in the developing pronephros. Epha4 and a7 are now expressed as three dots in the PT1 segments of the tubule, while ephb2 is detected in a wider domain encompassing the proximal, intermediate and distal segments. Ephb3 expression is restricted to the PT3 segment (Fig. 4).

Efna3 expression at stage 35/36 is almost identical to stage 32, although it appears to diminish in the branchial arches. In the pronephros, it is detected in the intermediate and distal segments of the tubule (Fig. 3). Expression of Eph receptors epha7 expands to the PT2 and PT3 segment, while epha4 is now detected in the entire proximal segments and posteriorly in the connecting tubule. Interestingly, pronephric expression of epha4 in the collecting duct is reminiscent of the Epha4 expression in the developing mouse kidney that has been shown to be essential for nephric duct insertion to the cloaca (Weiss et al., 2014). Expression of ephb2 and b3 is identical to stage 32 (Fig. 4). A summary of gene expression domains for Ephrin ligands and Eph receptors in the tubule segments at stage 35/36 is provided in Fig. 5.

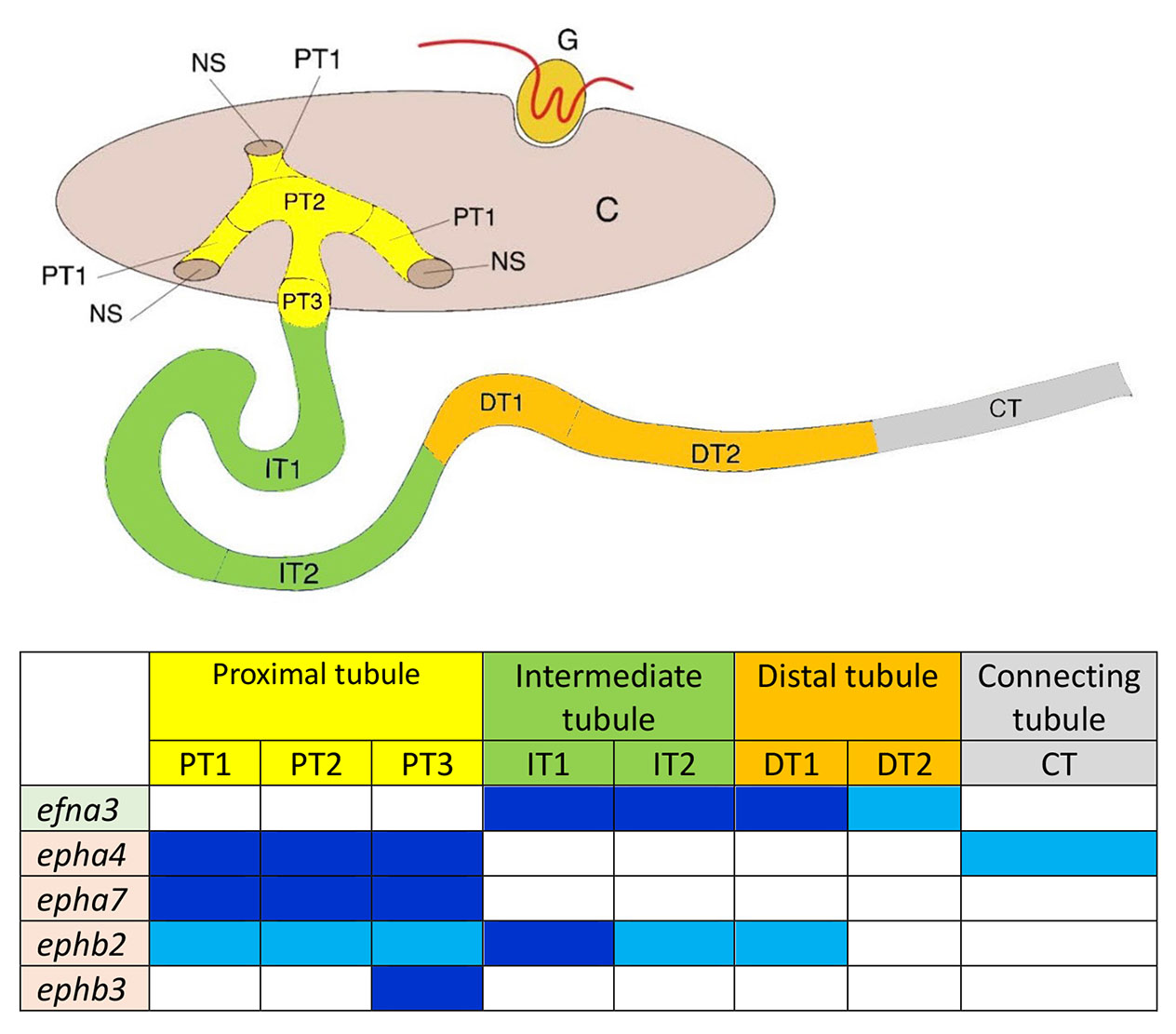

Fig. 5. Summary of gene expression domains for Ephrin ligands and Eph receptors in pronephros segments at stage 35/36.

Schematic representation of the pronephros and table (inspired by Raciti el al., 2008); Ephrin ligands are outlined in green and Eph receptors in light orange. Dark blue: strong expression. Turquoise blue: middle expression. Efnb2 expression is detected in the glomus at stage 35/36 and not in the tubule and is therefore not included in the table.

The expression domains of efna3 and those of epha4 and epha7 are strikingly complementary at stages 28, 32 and 35 suggesting that they may play a role in the patterning of the pronephric anlage. Dorso-ventral patterning of the pronephric anlage establishes a dorsal domain, which gives rise to the glomus and proximal tubule, and a ventral domain, which forms the intermediate and distal segments of the tubule. This process is largely dependent on Notch signaling, which is active in the dorsal domain (McLaughlin et al., 2000), whereas evi1/mecom may counteract Notch in the ventral domain (Van Campenhout et al., 2006). Efna3 and epha4 and/or epha7 may thus play a role in maintaining the boundary between these two domains. Although this has not been demonstrated for Efna3-Epha4/Epha7 signaling, crosstalk between the Notch axis and ephrin-Eph signaling is well documented (Ventrella et al., 2017). Such crosstalk plays a central role during vascular development, as demonstrated in the mouse retina where Efnb2-dependent arterial development involves an increase of Efnb2 expression downstream of active Notch (Iso et al., 2006), as well as ephrin acting upstream of Notch signaling (Stewen et al., 2024). Efnb2 appears to be expressed in the dorsal region of the pronephric anlage from st28 onward, and later in the glomus (Fig. S2). It is therefore possible that Efnb2 may also be involved in the dorso-ventral segregation process of the pronephric anlage dependent on Notch.

Materials and Methods

Xenopus embryos

Xenopus laevis were purchased from TEFOR Paris-Saclay (France). Embryos were obtained after artificial fertilization, and were raised in modified Barth’s solution (MBS). Stages were according to the normal table of Xenopus laevis (Nieuwkoop and Faber, 1975). All animal experiments were carried out according to approved guidelines validated by the Ethics Committee on Animal Experiments “Charles Darwin” (C2EA-05) with the “Autorisation de projet” number 02164.02.

In situ hybridization and embryo sectioning

To generate plasmids leading to synthesis of cRNA probes, PCR products were generated from cDNA library using specific primers listed in Table 2. PCR products were cloned in pCRII vector according to manufacturer instructions (Invitrogen) and digoxigenin-labeled cRNA probes were transcribed from linearized plasmids using SP6 or T7 polymerase. WISH was carried out as previously described (Le Bouffant et al., 2014) after embryo fixation in MEMFA for one hour and dehydration in ethanol (Harland, 1991).

Embryos selected for sectioning after WISH were further washed 3 times in PBS and embedded in gelatin for cryostat sectioning as described in (Bello et al., 2008). Sixteen µm sections were made on a Leica CM 3050S. Observation and images acquisition were performed on a Zeiss Macroapotome Axiozoom V16. Each magnification is indicated in figure legends. For each probe, 15-20 embryos of each stage were analyzed and 5 representative embryos were used for sections.

Alignment and tree

Proteins sequences were collected on Uniprot platform and Clustalw 2.1 free software was used for alignment and tree. Accession numbers of these sequences are the following:

EfnA3 Danio rerio (3a: XP_009292344.1; 3b: NP_571929.1), EfnA3 Medaka (XP_011483598.1), EfnA3 Xenopus laevis (NP_001080496.1), EfnA3 Xenopus Tropicalis (NP_001011360.1), EfnA3 Macaka mulatta (NP_001252612.1), EfnA3 Mus musculus (NP_001364045.1), EfnA3 Homo sapiens (NP_004943.1).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Authier, M. Amaral and E. Manzoni for excellent technical assistance in the maintenance of the Xenopus animal facility, as well as Claire Bouyer and Isabelle Gervi for technical support with WISH.

Abbreviations

MBS, modified Barth’s solution ; WISH, whole-mount in situ hybridization ; Efn, Ephrin ligand ; Eph receptor, Ephrin receptor ;References

Alarcón P., Rodríguez-Seguel E., Fernández-González A., Rubio R., Gómez-Skarmeta J. L. (2008). A dual requirement for Iroquois genes during Xenopus kidney development . Development 135: 3197-3207.

Barnett C., Yazgan O., Kuo H.C., Malakar S., Thomas T., Fitzgerald A., Harbour W., Henry J. J., Krebs J. E. (2012). Williams Syndrome Transcription Factor is critical for neural crest cell function in Xenopus laevis. Mechanisms of Development 129: 324-338.

Barua D., Winklbauer R. (2022). Eph/ephrin signaling controls cell contacts and formation of a structurally asymmetrical tissue boundary in the Xenopus gastrula. Developmental Biology 490: 73-85.

Bello V., Sirour C., Moreau N., Denker E., Darribère T. (2008). A function for dystroglycan in pronephros development in Xenopus laevis. Developmental Biology 317: 106-120.

Bourgin C., Murai K. K., Richter M., Pasquale E. B. (2007). The EphA4 receptor regulates dendritic spine remodeling by affecting β1-integrin signaling pathways. The Journal of Cell Biology 178: 1295-1307.

Buisson I., Le Bouffant R., Futel M., Riou J.F., Umbhauer M. (2015). Pax8 and Pax2 are specifically required at different steps of Xenopus pronephros development. Developmental Biology 397: 175-190.

Carroll T. J., Vize P. D. (1999). Synergism between Pax-8 and lim-1 in Embryonic Kidney Development. Developmental Biology 214: 46-59.

Cirio M. C., Hui Z., Haldin C. E., Cosentino C. C., Stuckenholz C., Chen X., Hong S.K., Dawid I. B., Hukriede N. A. (2011). Lhx1 Is Required for Specification of the Renal Progenitor Cell Field. PLoS ONE 6: e18858.

Costa R. M., Mason J., Lee M., Amaya E., Zorn A. M., (2003). Novel gene expression domains reveal early patterning of the Xenopus endoderm. Gene Expression Patterns 3: 509-519.

Desgrange A., Cereghini S. (2015). Nephron Patterning: Lessons from Xenopus, Zebrafish, and Mouse Studies. Cells 4: 483-499.

Fagotto F. (2020). Tissue segregation in the early vertebrate embryo. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 107: 130-146.

Fisher M., James-Zorn C., Ponferrada V., Bell A. J., Sundararaj N., Segerdell E., Chaturvedi P., Bayyari N., Chu S., Pells T., Lotay V., Agalakov S., Wang D. Z., Arshinoff B. I., Foley S., Karimi K., Vize P. D., Zorn A. M. (2023). Xenbase: key features and resources of the Xenopus model organism knowledgebase . Genetics 224: iyad018.

Fukusumi Y., Yasuda H., Zhang Y., Kawachi H. (2021). Nephrin–Ephrin-B1–Na+/H+ Exchanger Regulatory Factor 2–Ezrin–Actin Axis Is Critical in Podocyte Injury. The American Journal of Pathology 191: 1209-1226.

Giudetti G., Giannaccini M., Biasci D., Mariotti S., Degl'Innocenti A., Perrotta M., Barsacchi G., Andreazzoli M., (2014). Characterization of the Rx1-dependent transcriptome during early retinal development. Developmental Dynamics 243: 1352-1361.

Harland R. M. (1991). Appendix G: In Situ Hybridization: An Improved Whole-Mount Method for Xenopus Embryos. In Xenopus laevis: Practical Uses in Cell and Molecular Biology. Elsevier.

Hashimoto T., Karasawa T., Saito A., Miyauchi N., Han G.D., Hayasaka K., Shimizu F., Kawachi H. (2007). Ephrin-B1 localizes at the slit diaphragm of the glomerular podocyte. Kidney International 72: 954-964.

Helbling P. M., Saulnier D. M. E., Brändli A. W. (2000). The receptor tyrosine kinase EphB4 and ephrin-B ligands restrict angiogenic growth of embryonic veins in Xenopus laevis . Development 127: 269-278.

Heliot C., Desgrange A., Buisson I., Prunskaite-Hyyryläinen R., Shan J., Vainio S., Umbhauer M., Cereghini S. (2013). HNF1B controls proximal-intermediate nephron segment identity in vertebrates by regulating Notch signalling components and Irx1/2 . Development 140: 873-885.

Hwang Y.S., Daar I. O. (2017). A frog's view of EphrinB signaling. Genesis 55: e23002.

Iso T., Maeno T., Oike Y., Yamazaki M., Doi H., Arai M., Kurabayashi M. (2006). Dll4-selective Notch signaling induces ephrinB2 gene expression in endothelial cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 341: 708-714.

Kania A., Klein R. (2016). Mechanisms of ephrin–Eph signalling in development, physiology and disease. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 17: 240-256.

Kirmizitas A., Meiklejohn S., Ciau-Uitz A., Stephenson R., Patient R., (2017). Dissecting BMP signaling input into the gene regulatory networks driving specification of the blood stem cell lineage. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114: 5814-5821.

Le Bouffant R., Cunin A.C., Buisson I., Cartry J., Riou J.F., Umbhauer M. (2014). Differential expression of arid5b isoforms in Xenopus laevis pronephros. The International Journal of Developmental Biology 58: 363-368.

Lee H.S., Bong Y.S., Moore K. B., Soria K., Moody S. A., Daar I. O. (2006). Dishevelled mediates ephrinB1 signalling in the eye field through the planar cell polarity pathway. Nature Cell Biology 8: 55-63.

Lienkamp S., Ganner A., Boehlke C., Schmidt T., Arnold S. J., Schäfer T., Romaker D., Schuler J., Hoff S., Powelske C., Eifler A., Krönig C., Bullerkotte A., Nitschke R., Kuehn E. W., Kim E., Burkhardt H., Brox T., Ronneberger O., Gloy J., Walz G. (2010). Inversin relays Frizzled-8 signals to promote proximal pronephros development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107: 20388-20393.

Matsuda Y., Uno Y., Kondo M., Gilchrist M. J., Zorn A. M., Rokhsar D. S., Schmid M., Taira M. (2015). A New Nomenclature of <b><i>Xenopus laevis</i></b> Chromosomes Based on the Phylogenetic Relationship to <b><i>Silurana/Xenopus tropicalis</i></b>. Cytogenetic and Genome Research 145: 187-191.

McLaughlin K. A., Rones M. S., Mercola M. (2000). Notch Regulates Cell Fate in the Developing Pronephros. Developmental Biology 227: 567-580.

Murai K. K., Nguyen L. N., Irie F., Yamaguchi Y., Pasquale E. B. (2003). Control of hippocampal dendritic spine morphology through ephrin-A3/EphA4 signaling. Nature Neuroscience 6: 153-160.

Nieuwkoop P. D., Faber J., (1975). Normal table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin): a systematical and chronological survey of the development from the fertilized egg till the end of metamorphosis. North-Holland, Amsterdam.

Raciti D., Reggiani L., Geffers L., Jiang Q., Bacchion F., Subrizi A. E., Clements D., Tindal C., Davidson D. R., Kaissling B., Brändli A. W. (2008). Organization of the pronephric kidney revealed by large-scale gene expression mapping. Genome Biology 9: R84.

Reggiani L., Raciti D., Airik R., Kispert A., Brändli A. W. (2007). The prepattern transcription factor Irx3 directs nephron segment identity . Genes & Development 21: 2358-2370.

Rothe M., Kanwal N., Dietmann P., Seigfried F., Hempel A., Schütz D., Reim D., Engels R., Linnemann A., Schmeisser M. J., Bockmann J., Kühl M., Boeckers T. M., Kühl S. J. (2017). An Epha4/Sipa1l3/Wnt pathway regulates eye development and lens maturation. Development 144: 321-333.

Rudolph J., Zimmer G., Steinecke A., Barchmann S., Bolz J. (2010). Ephrins guide migrating cortical interneurons in the basal telencephalon. Cell Adhesion & Migration 4: 400-408.

Saxén L., Sariola H., (1987). Early organogenesis of the kidney. Pediatric Nephrology (Berlin, Germany) 1: 385-392.

Schlosser G. (2003). Hypobranchial placodes in Xenopus laevis give rise to hypobranchial ganglia, a novel type of cranial ganglia. Cell and Tissue Research 312: 21-29.

Schlosser G., Northcutt R. G. (2000). Development of neurogenic placodes inXenopus laevis. The Journal of Comparative Neurology 418: 121-146.

Session A. M., Uno Y., Kwon T., Chapman J. A., Toyoda A., Takahashi S., Fukui A., Hikosaka A., Suzuki A., Kondo M., van Heeringen S. J., Quigley I., Heinz S., Ogino H., Ochi H., Hellsten U., Lyons J. B., Simakov O., Putnam N., Stites J., Kuroki Y., Tanaka T., Michiue T., Watanabe M., Bogdanovic O., Lister R., Georgiou G., Paranjpe S. S., van Kruijsbergen I., Shu S., Carlson J., Kinoshita T., Ohta Y., Mawaribuchi S., Jenkins J., Grimwood J., Schmutz J., Mitros T., Mozaffari S. V., Suzuki Y., Haramoto Y., Yamamoto T. S., Takagi C., Heald R., Miller K., Haudenschild C., Kitzman J., Nakayama T., Izutsu Y., Robert J., Fortriede J., Burns K., Lotay V., Karimi K., Yasuoka Y., Dichmann D. S., Flajnik M. F., Houston D. W., Shendure J., DuPasquier L., Vize P. D., Zorn A. M., Ito M., Marcotte E. M., Wallingford J. B., Ito Y., Asashima M., Ueno N., Matsuda Y., Veenstra G. J. C., Fujiyama A., Harland R. M., Taira M., Rokhsar D. S. (2016). Genome evolution in the allotetraploid frog Xenopus laevis. Nature 538: 336-343.

Smith A., Robinson V., Patel K., Wilkinson D. G. (1997). The EphA4 and EphB1 receptor tyrosine kinases and ephrin-B2 ligand regulate targeted migration of branchial neural crest cells. Current Biology 7: 561-570.

Steinecke A., Gampe C., Zimmer G., Rudolph J., Bolz J. (2014). EphA/ephrin A reverse signaling promotes the migration of cortical interneurons from the medial ganglionic eminence. Development 141: 460-471.

Stewen J., Kruse K., Godoi-Filip A. T., Zenia , Jeong H.W., Adams S., Berkenfeld F., Stehling M., Red-Horse K., Adams R. H., Pitulescu M. E. (2024). Eph-ephrin signaling couples endothelial cell sorting and arterial specification. Nature Communications 15: 2539.

Sun J., Wang X., Shi Y., Li J., Li C., Shi Z., Chen Y., Mao B. (2018). EphA7 regulates claudin6 and pronephros development in Xenopus. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 495: 1580-1587.

Taylor H., Campbell J., Nobes C. D. (2017). Ephs and ephrins. Current Biology 27: R90-R95.

Van Campenhout C., Nichane M., Antoniou A., Pendeville H., Bronchain O. J., Marine J.C., Mazabraud A., Voz M. L., Bellefroid E. J. (2006). Evi1 is specifically expressed in the distal tubule and duct of the Xenopus pronephros and plays a role in its formation. Developmental Biology 294: 203-219.

Ventrella R., Kaplan N., Getsios S. (2017). Asymmetry at cell-cell interfaces direct cell sorting, boundary formation, and tissue morphogenesis. Experimental Cell Research 358: 58-64.

Wang X., Sun J., Li C., Mao B. (2016). EphA7 modulates apical constriction of hindbrain neuroepithelium during neurulation in Xenopus. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 479: 759-765.

Wang X., Sun J., Wang Z., Li C., Mao B. (2020). EphA7 is required for otic epithelial homeostasis by modulating Claudin6 in Xenopus. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 526: 375-380.

Wang X., Wang Z. (2021). Identification of the soluble EphA7-interacting protein Nicalin as a regulator of EphA7 expression. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 476: 213-220.

Weiss A.C., Airik R., Bohnenpoll T., Greulich F., Foik A., Trowe M.O., Rudat C., Costantini F., Adams R. H., Kispert A. (2014). Nephric duct insertion requires EphA4/EphA7 signaling from the pericloacal mesenchyme. Development 141: 3420-3430.

Weiss A.C., Kispert A. (2016). Eph/ephrin signaling in the kidney and lower urinary tract. Pediatric Nephrology 31: 359-371.

White J. T., Zhang B., Cerqueira D. M., Tran U., Wessely O. (2010). Notch signaling, wt1 and foxc2 are key regulators of the podocyte gene regulatory network in Xenopus . Development 137: 1863-1873.

Winning R. S., Sargent T. D. (1994). Pagliaccio, a member of the Eph family of receptor tyrosine kinase genes, has localized expression in a subset of neural crest and neural tissues in Xenopus laevis embryos. Mechanisms of Development 46: 219-229.

Xu Q., Alldus G., Holder N., Wilkinson D. G. (1995). Expression of truncated Sek-1 receptor tyrosine kinase disrupts the segmental restriction of gene expression in the Xenopus and zebrafish hindbrain . Development 121: 4005-4016.